Documenting the present isn’t completely dissimilar to documenting the past. There’s gathering up all the pieces to build a narrative and to some extent, a ticking clock. Stories get harder to tell the more time has passed.

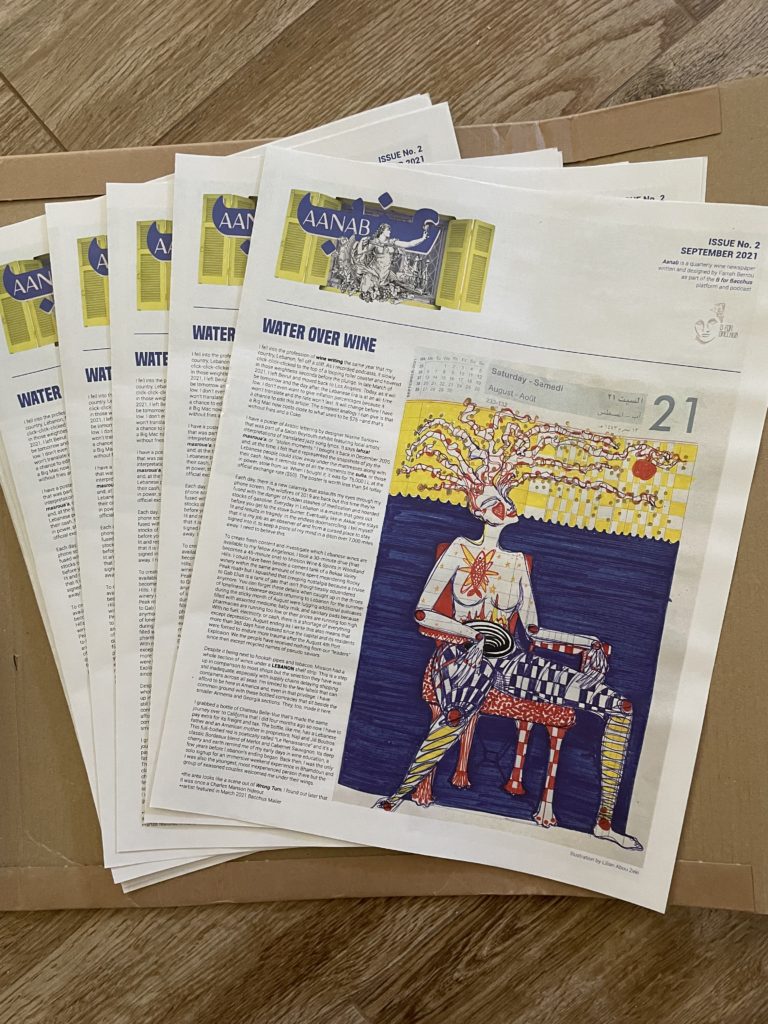

Wine professional Farrah Berrou, on her podcast B for Bacchus, does both. She explores the wine of the Fertile Crescent today by talking to wine makers, researchers, and writers, then she delves further into the past by highlighting the work of historians and archeologists who work on topics that intersect with wine. Berrou’s goal is never just to promote Lebanese wine, but to also use wine as a prism for how we think about different cultures and peoples, whether it is on her podcast or in her writing. Since launching in 2019, Bacchus has evolved to include not only the podcast, but also Aanab, a biannual newspaper designed and largely written by Berrou. Her Patreon account has also grown into a way, not only to support Berrou’s own production of paper goods, but also to support other regional artists and makers through commissioned content by other writers, photographers, and creators in Aanab,

*Berrou was recently interviewed for the first episode of Season 3 of Bacchus by one of Hazine’s editors, N.A. Mansour. You can listen to the episode here.

How did you get into wine, and specifically Lebanese wine?

It was a very practical side-effect of working in my family’s business of US imports. I’d left advertising and joined my dad’s mission to open a new branch of our retail stores. We were like the Costco (or any big-box store of the US) of Lebanon. He’d wanted to include an alcohol section in this new branch and told me to run it. I didn’t know the first thing about wine or spirits so I started going to tastings and doing online classes. I started looking at our own wine landscape and history. The more I learned, the more I realized there was a gap in global wine education when it came to wines of Lebanon or the neighboring region. Other parts of the world had full chapters. If Lebanon was mentioned, it would be a couple pages split withTurkey, Greece, and other places. It’s not that we were misrepresented; we weren’t allocated enough space for that to even happen.

Could you tell us a bit about B for Bacchus, and the origins of your platform?

B for Bacchus started informally during the summer of 2019. I say “informally” because I wasn’t sure what it was going to morph into, I just knew I wanted to show other people what I was learning. I hosted wine tastings at our store on the specialty floor that I managed. We created a whole “classroom” space that was on one large shared table with a screen where I’d explain the ancient history of wine in Lebanon to modern day challenges over the span of 2 hours. I kept it limited to 12 people because I wanted it to stay intimate yet casual so even novices wouldn’t be intimidated. I didn’t want it to be stuffy nor did I want it to seem like I knew everything about Lebanese wine because I didn’t – I still don’t. It was tough to market the classes given the location (being in a grocery store instead of a hip, central spot) but every one of the classes I had hosted there had the vibe I wanted: people unwinding over boutique Lebanese wines, wine-fudge brownies, Cheerios, and cheese. A few months later, right as the revolution began in October, I moved to podcasting and eventually, wine writing for foreign publications, like The Wine Zine, Eater and Tim Atkin MW’s site.

What kinds of voices are you trying to highlight on your podcast?

It started off as interviews with winemakers and winery owners. We’d discuss their story or how they got into the field. It felt like we only ever heard from them through the words of foreign writers on the off-chance that Lebanese wine would get featured in the New York Times, Forbes, or Bloomberg. Now I’m moving away from the winery spotlights and trying to make the content richer. This was a side-effect of lockdown. I started experimenting with shorter episodes that were just me talking about a random deep dive I went on. Season Two had historians, a special episode on arak that was a compilation of audio from listeners, and an interview with Michael Karam on his work for the Wine and War documentary. It’s important to have a place where we can unpack our own stories together, write them the way we understand them – or don’t. There is room for experts NOT from the region but I want to prioritize our perspective.

Is there a particular audience you are trying to reach?

Given that it’s in English, that alone is limiting in a way. My main audiences are in the US, Lebanon, and diaspora hotspots. Because it’s a niche of a niche, it could be of interest to anyone with a curiosity for wine even though, most of the time, it’s not even about wine all that much. I don’t do tasting notes or flavor profiles. I don’t think people care to listen to that and I don’t care to dissect it either. Anyone who’s up for culture from a new angle would find at least one episode to indulge in.

How do the winemakers and wineries you profile document their history? And how do newer wineries and winemakers engage with history/local practices to make their wines?

A few of them have some of their memorabilia on display at the wineries. I couldn’t comment on their private documentation but a lot of what you can access publicly is mainly foreign and local journalism. Whether or not these articles are 100% accurate and/or paid promotion isn’t always clear. I will say that as someone who is an independent researcher unattached to any institution, it can be tough to find sources. I also assume that a big chunk of my source material would be in Arabic and not splattered all over the internet. I get the sense that many of the newer players learn from their elders. Whether that’s older generations in their families or in the villages, there is a know-how that is passed on generationally that is separate from the training they get abroad. A lot of that knowledge isn’t documented, just oral. Chateau Musar’s Hochar family is seen as an example to follow given the brand they have built over the last century. The newer producers look up to Chateau Musar’s approach with low-intervention winemaking – nothing added and nothing taken away – but also with how they jumped head-first into the international market at the onset of the civil war. Now, Musar is an internationally recognized, natural wine leader that carved out its own identity and used indigenous grapes before it was trendy.

How is knowledge around wine making documented or shared, and how are practices recovered or “rediscovered”?

This is something I’m still trying to figure out. The Jesuits of Lebanon have great archives but access to them is another story. I get a lot of my information from journalists that did a lot of legwork before I came to the scene, like Michael Karam and Nabila Rahhal, but I also depend a lot on first-person interviews that I conduct myself through the podcast or otherwise. The issue with that is, like all oral histories, it’s biased and hard to verify. Nonetheless, these accounts and their documentation are crucial. My work –both written and audio– is now being archived by the UC Davis Library’s wine collection which is such a win. From their own admission, they have very little on the history of Lebanese winemaking. It’s an honor to be able to do something about that but also to know that my work isn’t just floating in the ether. It could help future generations understand more about our role in this industry. And for others from the region, there is finally some representation at America’s top enology school.

How is the work around producing distinctly Lebanese wine valued?

Honestly, it’s not. It seems like there is an appetite for the wine itself but there hasn’t been anyone to really challenge the marketing spiels that go along with the bottles or the press releases that get reprinted here and there. It becomes a reductive dichotomy of wine and war, pleasure and pain, luxury and loss. Nuance, richness, and consideration are lacking in the coverage we see today and that makes me wonder why we’re not given more space to be multidimensional people. I also feel that my own work as someone who wants this industry to be better is misunderstood too. If people want someone to regurgitate a tech sheet or wax poetic about Lebanon’s joie de vivre, they won’t get that from me. I want to be Lebanese wine’s cheerleader but I’m not here to be a mindless megaphone or biased brand ambassador.

Now if the question was about the value associated with producing the Lebanese wine in terms of a recognizable style or flavor profile, that’s a whole other thing. The country is between a rock and a hard place. You want to stand out because it’s a matter of survival: do you do it by taking risks to stand out or playing it safe to guarantee return on investment? No matter where they’re from, indigenous grapes require an extra level of education for the typical consumer and not everyone is curious or willing to fork over cash for something new. Sometimes people want to buy what they know or what they know they’ll like. The definition of Lebanese wine is still being written but I feel it will always be unfinished. I like that about it, there’s more room for play. When it comes to customers though, predictability can win over curiosity.

You worked professionally as a graphic designer. What is your design outlook and how does it feed into your Bacchus work?

I’m a stationery freak so I love that I’m able to execute ideas as they come. I’m not an illustrator but I have a simple, graphic style that I only developed through my own personal projects. Funnily enough, I don’t enjoy doing design work for anyone but myself and I’m much more of a conceptual/product designer. I like tangible, functional things. Working in advertising and graphic design gave me the skills to apply this wine theme to different channels. In November 2020, I decided to send out mailers every 3 months to Patreon subscribers. It used to be a collection of paper goods by creatives from the region but I’ve shifted it to a more collaborative format this year. Now, subscribers will still get four mailers: two of Bacchus cards or paper goods before they’re for sale on the shop and two with the latest issue of my biannual newspaper, Aanab, which is also sold separately on my shop. It’s a lot of work but assembling a thoughtful bit of snailmail is my love language and I’m looking forward to expanding Aanab and incorporating commissioned work from others too. The mailers let me be Santa every season and Aanab allows for me to publish without needing anyone’s approval first. The downside is that I have to do it all myself; from editing podcast audio to digitizing sketches to packing mailers. Despite it being a ton of work, I enjoy getting lost in the details.

Do you have any projects or new directions you’re hoping to take your platform in?

I want to see where Aanab is going to go. So far, I’ve covered the French influence on Lebanese wine and a personal essay on why this work is important even if it doesn’t always feel like it. I want to expand its sections and coverage little by little. I also need to get back to the podcast as that’s really one of the pillars of the body of work but there is a part of me that wants to start fresh with a limited-run podcast – one that is still about wine and the region but with a coherent storyline throughout the episodes. Other offshoots like WineWomen&ME (highlighting women in wine from the region on socials) and Virtual Table (the online version of the classes I was hosting in Beirut) have potential for more but I don’t want to create more pressure for myself so I’m also trying to prune the vines so my energy is channeled effectively. Like I said, I have to be realistic with the fact that I’m the only one nurturing these roots.

If people want to learn more about wine or spirits of the Mena region, are there additional resources, voices, and projects you might point people to?

LSE’s podcast, Instant Coffee, had me on as a guest and simultaneously introduced me to the work of Jamal Rayyis and Arthur Asseraf who were featured in the same episode. Other names to look into would be Patrick McGovern, Elizabeth Saleh, Helene Sader, Nawal Nasrallah, and Graham Pitts. I’ll keep sharing whatever and whoever else I find!

Farrah Berrou is a writer who splits her time between Los Angeles suburbia and Beirut, Lebanon. She is a Contributing Editor for NY-based The Wine Zine, the creator of the B for Bacchus platform/podcast and its biannual newspaper, Aanab. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter.