By Marianne Dhenin and Mohamed Gamal-Eldin

(All image credits belong to Gamal-Eldin)

On a tree-lined side street just around the corner from Washington Square Park – and close enough to Zooba, the hip Cairo- and now New York-based Egyptian street food restaurant, to warrant traipsing over for lunch– scenes from everyday life in Cairo are on display at New York City’s Center for Architecture.

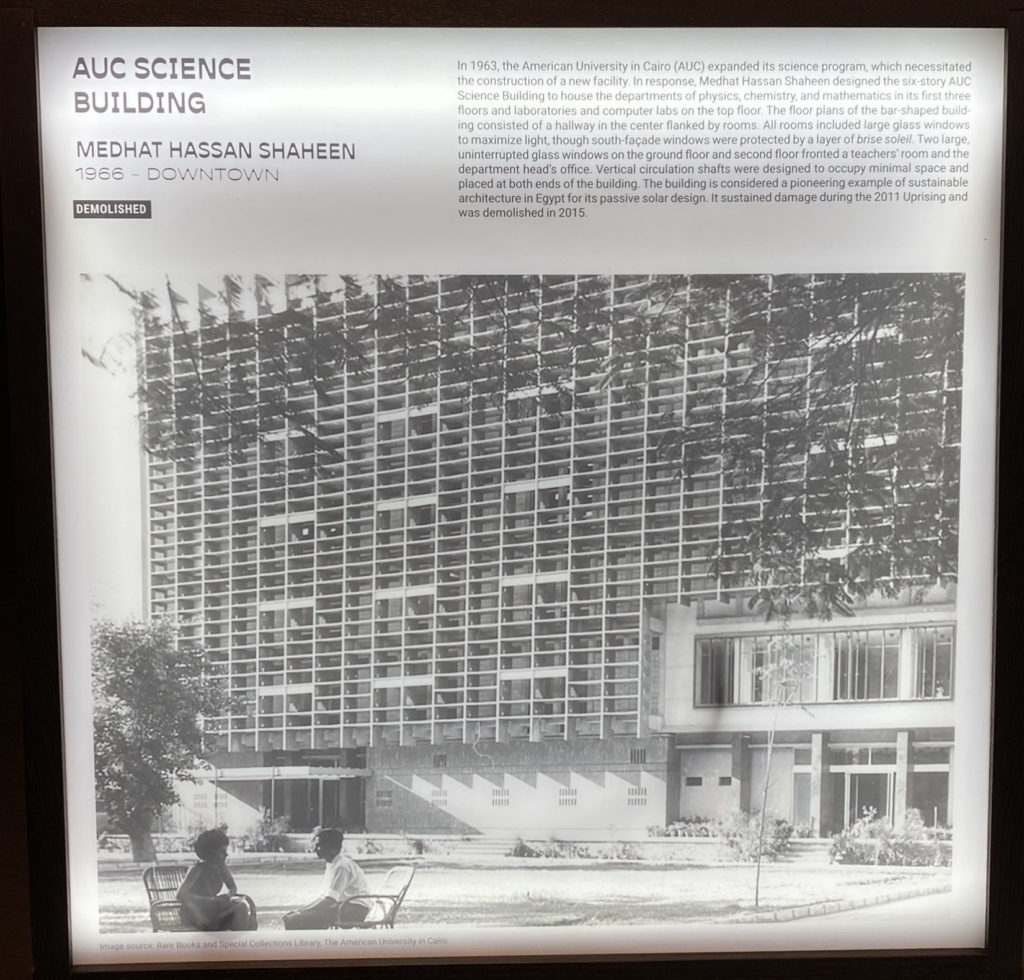

A backlit black-and-white image at the center of the room shows a woman in a striped shirt and knee-length skirt, flanked by palm trees and bamboo lawn furniture, the sort that’s still ubiquitous at sporting clubs and cafés across Egypt, posing for the camera on the Nile’s Mounira Island. A thirty-one-story high-rise towers in the background. Another image shows a pair of students seated in those same bamboo chairs on the lawn outside the American University in Cairo’s six-story Science Building, its large glass windows protected by an elaborate brise soleil.

While the scenes feel timeless, the focus of the exhibition is not the characters at all. Instead, the focus is on the built environment they inhabit. The images have been brought together, in part, to challenge the anthropocentrism of history and underscore the impermanence of modernist buildings in this city on the Nile. The Sabet Sabet Building, built in 1958, which rises in the background of the image from Mounira, still stands in Garden City. But the Science Building on AUC’s downtown campus, designed by architect Medhat Hassan Shaheen and built in 1966, has been abandoned and demolished, victim to what academics call Cairo’s urbicide.

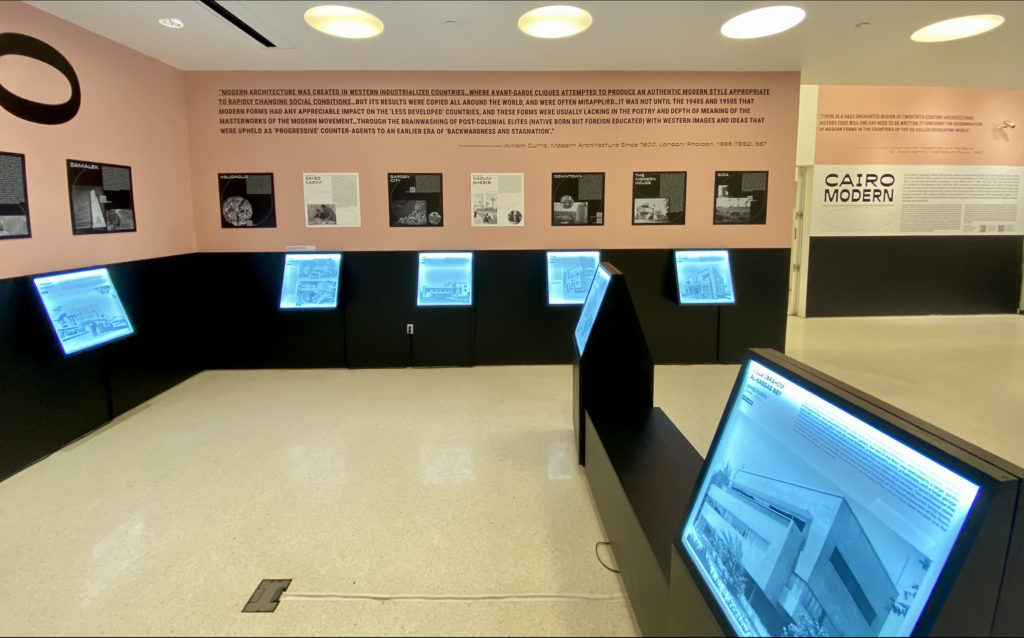

The images comprise Mohamed Elshahed’s exhibition, Cairo Modern, which was on display from October 1, 2021, to March 12, 2022. It is one in a string of curatorial and written projects from the Egyptian architectural historian and curator that situate Egypt’s modern architectural movement within global architectural histories while simultaneously calling for the decolonization of the field of architecture and the protection of Cairo’s Modernist buildings. Occupying the Center for Architecture’s ground-floor gallery, the exhibition is organized in three tiers, one above the other. The first encompasses a series of large-print quotations embossed on the gallery’s flamingo pink walls that speak to the place of Egypt, and more generally the Global South, within architectural history. These are shown above images of prominent buildings constructed across Egypt’s capital city roughly between 1930 and 1970, illuminated on lightbox panels at waist-level. The majority of the work was done by elite university-trained male architects for clientele who were also middle- or upper-class Egyptians.

Sandwiched in between is a final tier of eye-level panels, offering biographical and historical commentary on Egypt’s twentieth-century master plans, neighborhoods, and architects. The panels display personal details about the lives and work of elite Egyptian architects Sayed Karim and Naoum Shebib, who was behind the Sabet Sabet Building, and the Italian-born architect Mario Rossi, who worked at Egypt’s Department of Public Works and served as one of the three chief architects on Cairo’s neo-Mamluk style Diwan al-Awqaf (Ministry of Religious Endowments) in the early twentieth century. Following these panels around the room counter-clockwise from the entrance leads you to a series of technicolor covers of Sayed Karim’s al-Emara magazine, published in Cairo from 1939 to 1950, spread across one wall like dealt cards, alongside a description of the rise of architectural periodicals in the Middle East beginning in the 1930s.

The images and panels also contrast with the wall-sized texts, three of which feature problematic and egregious misrepresentations of architecture in Egypt and the Global South from architectural historian William Curtis and the American doyen of Modernist architecture Frank Lloyd Wright. This jarring arrangement is meant to force visitors – as soon as they step into the space – to question the position of practitioners and the built environment of the Global South and Egypt, in particular, within the western-produced canon of modern architecture.

However, while Curtis might serve as a successful foil for Egyptian architecture to the trained architect, for visitors unanointed in the field and unaccustomed to reading the built environment as source material, Egyptian voices feel muted. The decision to thrice frame quotes from Curtis and Wright on walls looming over the exhibition’s other panels draws focus away from Egyptian architects and their works. With the exception of Sayed Karim, who is granted a wall-sized quote on the connections between materiality and local forms of design – in particular, the arch, the column, and the dome – twentieth-century Egyptian architects are relegated to smaller biographic panels or photos of their projects. It seems the words of these English and American architects continue to hold power over both the curator and the exhibition. They may have been better left out.

A redeeming feature for the layperson, opportunities for interested visitors to explore further are sprinkled throughout the exhibition. Many panels feature QR codes that link to Google Maps’ locations, documentary films, and further reading. Just past the covers of al-Emara, a detailed timeline of twentieth-century architectural moments is splashed floor to ceiling across an entire wall. From a few paces away, bolded moments and select images stand out along the timeline, allowing visitors to contextualize the exhibition and challenging them to question their conceptions of Modernism’s Western-centered chronology. If you spend long enough standing in from of the timeline, you’ll also spot more obscure details, like a picture of a young Zaha Hadid used to mark the architect’s birth in 1950 or that famous Egyptian composer and trained architect, Abu Bakr Khairat, earned his master’s degree in planning in 1939. A copy of Elshahed’s monograph, Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide (American University in Cairo Press, 2020), which serves as a companion text to the exhibition, is also available for perusal at the entrance.

Before venturing further into the exhibition, one might also stop to ponder another, more implicit question: What is Cairo’s place within the historiography of Egypt and the Global South? Cairo is at the center of most historical narratives. That Cairo holds an outsized place in Egyptian historiography may have to do with the abundance of source material on the city and its role as a center of political power throughout recent history. However, this tends to elide the fact that Cairo extracts its wealth and power from the landscapes of the Nile Delta and Upper Egypt. Cairo’s hegemony in historical writing plays out in today’s politics and pop culture –tangibly demonstrated through films– as Egyptian administration remains centralized in Cairo and the needs of the governorate of Cairo are given greater weight than those of provincial cities and towns. Cairo’s hold on Upper Egypt, its people, and its economy is almost colonial.

While Elshahed’s exhibition again centers Cairo, its call to decolonize architecture and recenter historiographies also hints at other significant questions. Although it has not done so itself, the exhibition asks us to consider, as researchers, historians, and storytellers, how we can pick up the slack and center underrepresented peoples and peripheral spaces in our work. Within the fields of urban and architectural history, publications like Arab Urbanism, a magazine founded by a collective of urban historians, geographers, and architects, offer a path forward in this respect.

Beyond Cairo Modern’s critique of architectural studies of Modernism, the exhibition also challenges an Egyptian state that shows open contempt for its Modernist architectural heritage, preferring instead to demolish twentieth-century villas, residential high-rises, and administrative buildings and spend state funds parading what historian Hussein Omar aptly called “military futurism in pharaonic drag” through the buildings’ remains. “In many cases,” reads a block of text near the exhibition’s entrance, “the published images of the now-demolished buildings … are the only surviving evidence such buildings ever existed.” The regime flaunts Egypt’s ancient past as propaganda for foreign audiences and bait for tourist dollars. It neglects its more recent heritage as a means of obscuring the nation’s modern history of ruinous economic reforms, political turmoil, soaring rates of political incarceration, and the specter of revolution. “Modernism in Egypt has not been granted national heritage status,” writes Elshahed, “as if history stopped at the threshold of the twentieth century.”*

The regime’s interest in curating a sanitized statist historical narrative through selective architectural conservation is part of what urban researcher Omnia Khalil has called its “political urban agenda.” So, too, is the muddled mass of new construction — 7,000 kilometers of roads, the world’s widest cable-stayed bridge, an in-progress skyscraper that promises to be Africa’s tallest — carved into Egypt’s landscape in recent years. With costs in the billions of dollars, these concrete vanities are intended as symbols of modernity and progress. International financial institutions laud them as evidence of the nation’s mighty construction industry as they dole out development loans, whose conditions, including increasing public transportation costs and cutting subsidies on staple foods, require ever greater sacrifice from Egypt’s poorest. Building owners also have an economic interest in ensuring Egypt’s Modernist buildings remain unprotected, sometimes purposely damaging a building’s structural integrity to speed the process of securing a demolition permit, allowing them to build anew and turn a profit.

As the regime demolishes twentieth-century Modernist buildings to make way for new construction, it also uproots public squares, paves over parks, and levels semi-autonomous or “informal” neighborhoods, called ashwa‘iyyat, home to the nation’s urban poor. In doing so, it replaces spaces that might foster assembly among Egyptians still desperate for the demands of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution — bread, freedom, social justice — with dystopian structures, like strategically placed elevated highways that double as watchtowers for the state.

Thus, the exhibition is also part of a greater mission to preserve Egypt’s Modernist past. It is itself a way of memorializing twentieth-century Egyptian Modernism through photography and magazine culture and an antecedent to a larger archival survey of Modernist architecture in Egypt and the region that has yet to be completed.

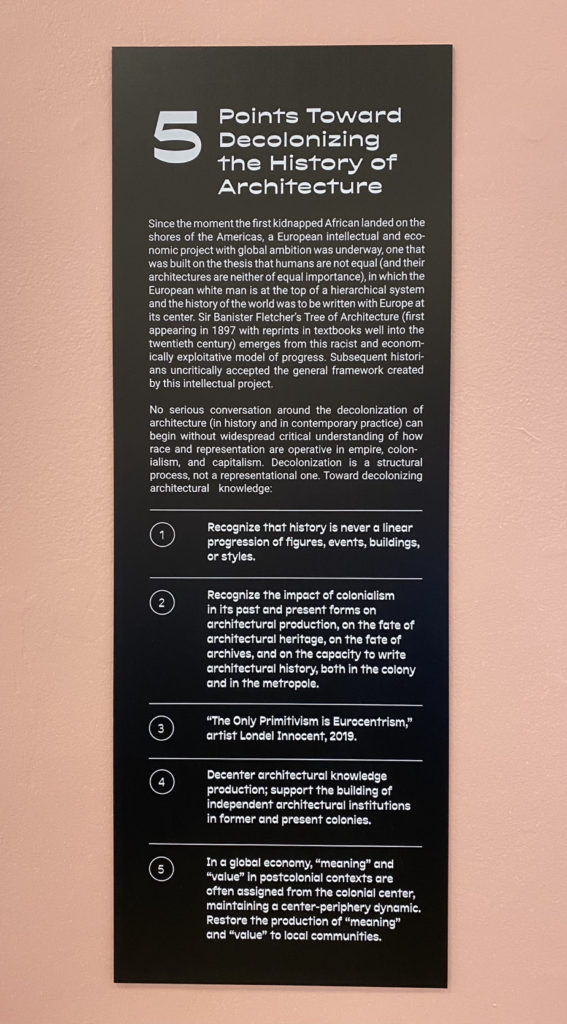

Ultimately, a tour through Cairo Modern is bound to leave visitors feeling like Elshahed has a lot more to say, which the size of the one-room display makes impossible. The invitations for further engagement that Elshahed has nestled throughout, like the QR codes on many of the panels, give the exhibition life outside the walls of the Center for Architecture. They also hint that everything on display is part of a much larger project: a continuation of Elshahed’s oeuvre and a call for the decolonization of the field of architecture. Centered on a pillar adjacent to the timeline of architectural moments is a placard that lays out Elshahed’s manifesto for decolonization: “5 Points Toward Decolonizing the History of Architecture.” This call to action is an attempt to move the pendulum of agency away from the west as the signal progenitor of design and building and give agency to works that western historians have historically left out of the canon. The exhibition works toward this project by platforming architecture and design in the Global South, specifically, Egypt, and creating a rich repository of texts and images from Modernist Egypt. These resources could one day form the core of a new grassroots-led institution to support education on Egypt’s architectural heritage and history of its built environment, fulfilling one of Elshahed’s 5 Points: “Support the building of independent architectural institutions in former and present colonies.”

As for giving the indigenous architect a platform, beyond the few chosen for representation in the western canon – like Hassan Fathy – Elshahed’s exhibition and book pave the way towards including a number of prominent architects and designers, like Sayed Karim and Naoum Shebib, in the curriculum of Global Modernism. Further, by including Frank Lloyd Wright and William Curtis, Elshahed begs architects to critique their positionality in light of colonialism and today’s neoliberal capitalist remaking of cities. When we can demystify these architectural giants and re-center local architectural achievements, maybe then can we move towards a truly decolonized history of architecture.

With similar themes in mind, Elshahed has curated several other exhibitions in North America, Europe, and the Middle East. Each explores modern Egypt through its architecture, infrastructure, and objects of everyday life — a black Singer sewing machine decorated with a golden sphinx, a worn, plastic radio with a white dial and orange face, a rusted metal cooler that once held Coca Cola. His Modern Egypt Project, a pop-up exhibition, showed in downtown Cairo in 2016 before parts were moved to the British Museum in London. Modernist Indignation, a predecessor to Cairo Modern, introduced British audiences to al-Emara and was named the most outstanding overall contribution at the 2018 London Design Biennale. New Schools, Future Egyptians, shown at the 2019 Sharjah Architecture Triennial, co-curated with with Farida Makar, revealed the infrastructure that facilitated Nasser-era education reform. Each of Elshahed’s projects grapples with similar questions: How do architects from Egypt and the Global South practice and adapt Modernism to their own styles? What does it mean to be modern? What implications does Cairo-centrism have on the narrative? Who holds the power to say which architects and which works should be canonized? With Cairo Modern, Elshahed has once again invited audiences to engage with these questions.

While the exhibition in New York City has closed, versions of it are already on display or scheduled to be shown at Ain Shams University and Cairo University in Cairo and in Mexico City, again revealing Elshahed’s commitment to raising the status of Egypt’s Modernist architecture across the Egyptian populace and the Global South.

*Mohamed Elshahed, Cairo Since 1900, p. 29.

Mohamed Gamal-Eldin is a historian who graduated from the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University-Newark. His dissertation was entitled: Cities of Sand: Reshaping the Environment, Building Towns, and Finding Modernity in the Isthmus of Suez, 1856-1936. His most recent article, “Searching for a Past: French Colonial Memory of Ismailia in the early 20th Century,” was published in 2022 by Monde Arabe.

Marianne Dhenin is a disabled journalist and historian. Currently, she is a Ph.D. candidate in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Basel, a researcher in the Leibniz Cooperation Project “The Historicity of Democracy in the Arab and Muslim Worlds,” and a member of the academic staff at the Leibniz Institute of European History. Her dissertation explores how disease and public health shaped the social and spatial order of late 19th- and early 20th-century Egyptian cities.