Canadian arts magazine, BlackFlash, has long been platforming the diverse and divergent in visual contemporary art. In its latest issue for Fall/Winter 2021, Infinities (38.3), it focuses on Islamic art, defined loosely, generously and inclusively; applied to everything from Instagram posts to ceramics to Microsoft Word, as a medium. The issue represents an important moment in the history of Muslims living in Canada, which understands them as part of the art scene, but also seeks to highlight how many immigrant Muslims are also taking accountability as settlers living on colonized land; the essays and artists in the issue question their relationship to the land and their responsibilities to its Indigenous peoples, as well as other systems of oppression such as anti-Blackness and Islamophobia. Infinities even looks beyond Canada and includes on its front cover an image of Palestinian tatreez by artist Samar Hejazi, which, as a medium, by sheer means of its existence, is a stand against Israeli settler-colonialism.

One of the reasons the Hazine team was so excited to highlight BlackFlash was that the prospect of an Islamic arts issue of BlackFlash was novel: documenting such a project is critical to anyone who identifies with Islamic art –Muslim, however that is defined, or non-Muslim alike– and might want to embark on a similar project. The careful curation of BlackFlash 38.3 is due to its guest editor and BlackFlash editorial committee member, Nadia Kurd. She tells us in this interview how this issue came to be, how it fits into BlackFlash’s overall vision, working with writers, and how Infinities might inspire the Canadian art scene.

All images provided by Nadia Kurd.

You can order a digital or physical copy of Infinities here, read much of the issue online here and enjoy some of the web features related to the issue here. Additionally, Kurd commissioned a series of responses to the issue, which are forthcoming.

At Nadia Kurd’s recommendation, we encourage you to support the Canadian Council of Muslim Women, NISA Homes, and the Indian Residential School Survivor Society.

Tell us what prompted this special issue and who else has been involved.

For the past few years, I have been reflecting on the number of artists and writers in Canada who, in various ways, have drawn from the diverse practices associated within the broad spectrum of Islamic art. However, given the current pandemic, there were limited opportunities to showcase this work in a wide-ranging and accessible way. As I was already on the editorial committee of BlackFlash Magazine, I approached managing editor Maxine Proctor with this idea and her positive, swift response was encouraging and really spurred me to think about the project more concretely.

I should also mention that the project really isn’t a survey; I wanted to engage writers and artists who had personal connections to Islamic visual heritage as a way to emphasize that there are diverse perspectives that may or may not be shared in broader communities, be they cultural or religious.

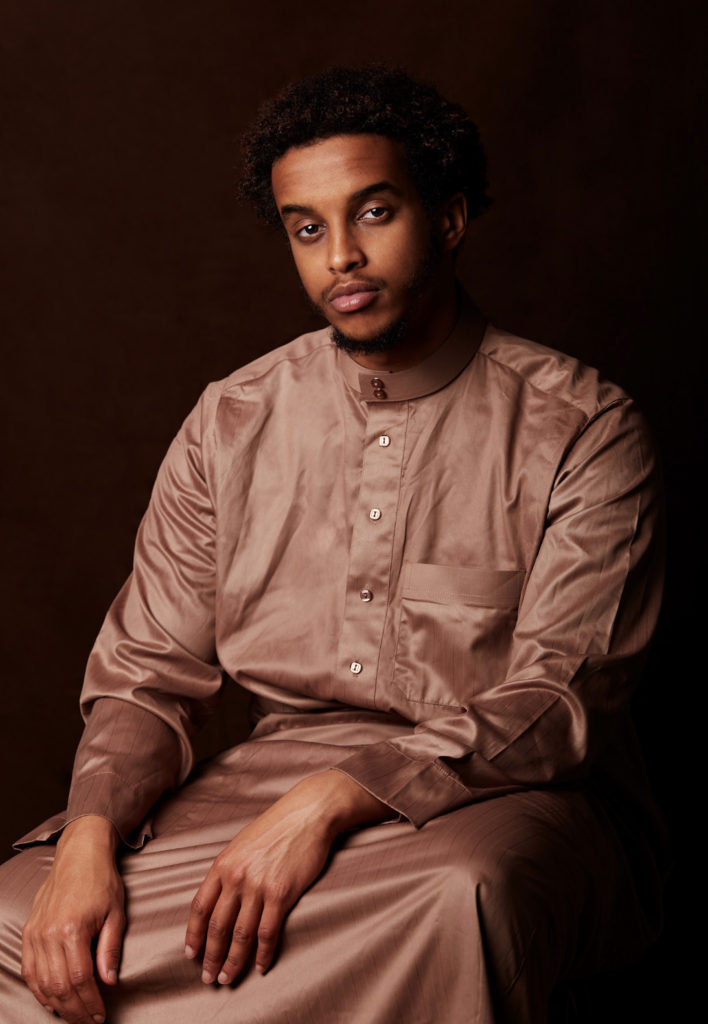

There have been a number of incredible people involved in this project, namely Jamelie Hassan, Abdi Osman, Farheen HaQ, Tammer El-Sheikh, Alize Zorlutuna, Shaheer Zazai, Azadeh Elmizadeh, Habiba El-Sayed, Timiro Mohamed, Nehal El-Hadi, Sam Shahsahabi, Faisa Omer, Tazeen Qayyum, Yasmeen Nematt Alla, Riaz Mehmood, Rolla Tahir, Moska Rokay, Samar Hejazi and Sanaa Humayun.

In addition to the issue, I have also invited additional writers to expand the conversations and ideas contained in the print version. These writers include artists/writers such as Ibrahim Abusitta, Charlene K. Lau, Susan Blight, and Nur Sobers-Khan. Their responses will be available online at BlackFlash.ca this spring.

What has been BlackFlash’s audience and do you hope the special issue will expand its audience?

As a magazine based in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, BlackFlash has long been a Prairie-focused publication. Its audience has primarily been artists and organizations committed to lens-based, contemporary art. The magazine was founded in 1983 by one of Canada’s earliest artist-run centres, The Photographers Gallery. The magazine was also originally published as Photographers Gallery, but was renamed BlackFlash the following year as it was quickly recognised as an important platform for contemporary photography in the region.

In the past three years, BlackFlash has expanded its editorial focus and looked beyond lens-based practices. This has really opened the possibility for the production of an issue like Infinities. I do hope that this issue not only expands the magazine’s reach, but also provides its long-time readers with a fresh perspective of the arts in Canada. I am also encouraged by the increased readership by those outside of Canada who will engage with the ideas in the issue, which are also globally relevant.

Most of all, a number of the artists and writers in this issue have been first-time contributors to a national publication – and I hope that they are encouraged to write for other magazines in the future.

How have Muslims shaped the art scene in Canada and how have they previously been represented in Canadian art media?

I think the contributions have been immense yet largely unacknowledged. Artists like Jamelie Hassan have really paved the way for Canadian artists to weave Islamic visual culture with contemporary social and political concerns since the 1970s. Her ability to do this has long inspired me – going back to my time as a fine arts student. For example, the work Bench from Cordoba (1981) recalls the everyday beauty of Andalusian designs and tile work, but brings attention to the context and time of such benches. This work also has material and historical connections to the work of emerging artist Habiba El-Sayed who also examines the historicity of ceramics and the circulation of patterns, ideas and gendered tropes in her work.

There have been a number of important exhibitions by artists like Jamelie Hassan, Tazeen Qayyum, Abdi Osman, but also other creative endeavours such as Zarqa Nawaz’s television series Little Mosque on the Prairie, which ran for six seasons (2007-2012). There are numerous writers as well and in particular, this past year, I was very much inspired by a beautiful piece by Nehal El-Hadi in This Magazine. To go back even further in time, the artist Ameen Sied Ganam (1914-1994) known as ‘King Ganam’ was a fiddling legend in Canada from the 40s to the 60s. The special issue of BlackFlash provides a glimpse of what is happening in Canada at the moment.

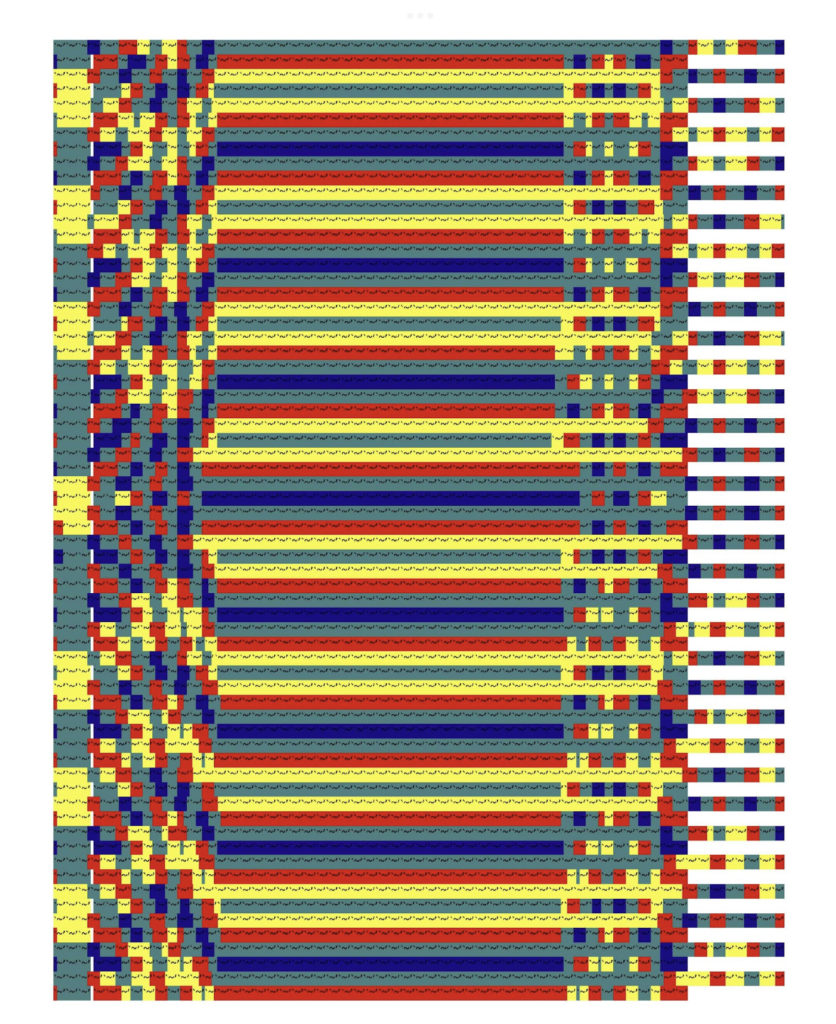

With each issue of Infinities, readers get a beautiful print that resembles a rug, but has something a bit…digital about it, even in its material, printed form. Can you talk a bit about the process and intention behind the inclusion of Shaheer Zazai’s risograph work ‘BFM8.511?

Artist Shaheer Zazai was selected for the art commission piece for BlackFlash because of his ability to transform the medium of Microsoft Word to create works of art that draw inspiration from the tradition of rug making. His work is intricate, colourful and most of all, innovative in its conceptual and artistic approach. Each of his prints are vastly different in their patterning. However, the process to create the warp and weft of the image follows the conventions of the software. Creating a risograph for this project was a challenge for Shaheer as he had to then translate his process to the requirements of risograph printing – it was great seeing the final product!

Another side of the commission involved contrasting his art with the overemphasis on exhibits focused on the production of ‘war rugs’ from Afghanistan which scholar Jamal Elias points out, “are produced for the market” and ignore the “realities of rug brokers and dealers.” Shaheer’s work cuts through this narrative conceptually, materially and ethically – leaving an impression of dynamism of this living art form.

What was your approach to assembling the Infinities issue of BlackFlash?

For this issue of BlackFlash, I wanted to capture the rich diversity of practices, ideas, artists and cultural backgrounds. Additionally, I wanted to engage established, mid-career and emerging contributors. Given this range, the name of the issue ‘Infinities’ seemed fitting as it also emphasizes both the breadth of inspiration, approaches and materiality used by the artists. Of course, this term also resonates with Muslim religious practices and thought.

In conjunction with the magazine, there are a series of web stories focused on emerging artists Shaheer Zazai, Habiba El-Sayed, Alize Zorlutuna and Faisa Omer. In these videos, we hear each artist describe their influences, mediums and how they came to their practice; this is also an important component of the project and for me, another avenue for audiences to enter the issue. The contributors had significant leeway to discuss the themes and concerns that mattered to them the most, and in many ways, I simply provided a platform for participants to explore their ideas.

Overall, I hope that the dialogue and exchange I’ve had with each artist in the production of this issue continues in other facets of my future curatorial work.

The issue, although centered on Muslim artists, also displays sensitivity to Indigenous artists and open acknowledgement that Canada is a settler colonial state. How important was it to you as the editor and to BlackFlash as a publication that this perspective was reflected?

Oh, this was critically important to the publication and for me as the editor. In recent years, BlackFlash has made important steps to include and profile Indigenous voices and their issues.There is also a growing awareness within various arts communities of the need to address the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation calls to action. Many Muslim settlers –Muslim immigrants, not the descendants of enslaved Muslims– in Canada recognize how Indigenous peoples have been subjugated and treated like second-class citizens by the state, really not even as citizens at all of their own traditional territories.

The histories of settler colonialism are interrelated with and depend on narratives that mythologize the past. As a result, they minimize reality and at times, even co-opt stories to present an illusion of change in society. I think the role of artists and writers is to connect and discuss some of these issues in path-breaking ways. We also live in a time and place where there continues to be inequality, not just in Canada but globally. By centring Muslim artists –or rather, artists who are Muslims to varying degrees– some of these histories can be illustrated. We need these collective efforts to change how things are typically conceived, processed and done in our contemporary society – one where Muslim people of colour are not considered as secondary citizens, or at worst, illogical and inhuman.

I admire the choice to include Palestinian tatreez on the cover in a stunning piece by Samar Hejazi. Oftentimes, Islamic art excludes tatreez, which is seen as craft because it is embroidery and is worn in everyday life. The field of Islamic art history theory, represented well in the work of Wendy Shaw, has been working to change that and broaden the terms. How do you define Islamic art in the issue? How does your definition understand method and technique?

Much like Shaheer Zazai, Samar Hejazi is also innovating with textile arts. Also like Shaheer, I believe she recognizes that these practices are not part of the ‘minor arts’, but fulfil our deep connections to places and heritage. Samar’s work shows the durability of tatreez and is cognizant of its symbolic value to conversations about Palestinian self-determination, cultural preservation and knowledge. Her work also indirectly emphasizes women’s roles in keeping cultural traditions alive – the decision to place her work on the cover was to present tatreez with all of this complexity – and to convey the unequivocal message that Palestinian self-determination and the right of return is a global human concern.

In terms of my definitions of Islamic art, I really don’t have any. I do, however, think of Islamic art as a living and evolving tradition; one that has both Muslim and non-Muslim contributors, but one ultimately connected to the history of Islam in the world. For this issue, it was up to each contributor to define what this meant to them – some chose to and some did not.

Archives and Canadian Muslim archival projects are included in the issue, through a lovely essay by Moska Rokay. How do you understand the relationship between art and archive?

There are a number of artists and writers, like myself, who draw from archival research to understand and make sense of the past. Most arts organizations – both small and large – rely on keeping archives for institutional memories and early work, which are connected to the development of art histories. Archives, which can often be inaccessible either because there are expensive paywalls, lack of open online sources or even the locations of archival holdings in a vast country like Canada, are also deeply important to tell stories and situate communities.

The Muslims in Canada Archives (MiCA) initiative is an important institutional project that preserves the histories of Muslims. Their mandate to help Muslims in Canada “to seize their narrative power” is a formidable one. As they point out, the burden of seeing Muslims through the lens of terrorism, violence and extremism is great – and MiCA is a strong step towards combating some of the animus against Muslims. However, I think combating anti-Muslim sentiments has to be much broader and must also come from elected officials across the country; only this past summer, Canada witnessed a violent hate attack on a Pakistani Muslim family, which saw the deaths of four members of the Afzaal family. I think archives can help build narratives on the histories of Muslims in Canada and offer insights into our connections to places.

What do you hope for the future of Islamic art in Canada? Specifically, what role do you think BlackFlash will take in shaping that future?

My hope is that there is an increase in conversations, exhibits and writings on artists who engage with the field of Islamic art history. I believe that this needs to be largely community-driven and ideally also brings together people outside of mainstream art communities and from various socio-economic backgrounds. I also hope that such trajectories lead to projects that emphasize collective practices and work towards a greater awareness of Islam and Muslims in Canada.

In the past, I have seen museums and galleries mount exhibits that cause harm to Muslim communities and frame cultural production from Muslim majorities only through the lens of war. One does not really have to look far to have representative curators, writers and artists that can take on more nuanced approaches to Islamic art. I am encouraged by the work of the contributors of this issue of BlackFlash and feel that there is so much potential to change the narrative and capacity of Muslims in Canada; this issue was a small step towards this goal.

All images were supplied by Nadia Kurd.

Nadia Kurd (she/her) is an art historian and curator based in Amiskwaciwâskahikan / ᐊᒥᐢᑲᐧᒋᐋᐧᐢᑲᐦᐃᑲᐣ (Edmonton) in Treaty 6.