By Jean Druel and N.A. Mansour

In light of recent events in Lebanon, we want to encourage you to donate to support domestic workers via Egna Legna, an Ethiopian domestic worker-run organization based in Beirut Lebanon, which has over the past three years assisted domestic workers including victims of horrible abuses to the best of its ability. We also recommend donating to Beit el Baraka. Use this tool to find more places that need donations.

If you’re an Arabist, think about the digital library or archive catalogues you use and then try to count the number that have interfaces and data available in Arabic. There are few in Arabic, although there are more catalogues and tools that are in Turkish. In addition, the design of these resources often is adapted without much alteration from tools produced for European-language materials for European-language audiences. It dismisses even the possibility that other intellectual histories rooted in different contexts function differently and require different things from their organizational standards; it also dismisses the notion that technologies are neutral and that they are inclusive.

The Arabic intellectual tradition is built around commentaries all expressing different and often diverging opinions, although they are often tied to the same text. So in order to study, for example كتاب سيبويه Kitāb Sībawayh, you need to be familiar with existing critical editions of the text. You might also want the commentaries written on it. You also naturally want the secondary sources on it as well: Arabic journal articles and monographs, as well as those written in other languages. Your institution’s standard catalogue might not be as much help here. You need a catalogue built to these bibliographic purposes. The AlKindi catalogue, developed by the Dominican Institute for Oriental Studies (IDEO) is the best solution to this problem of needing research tools in Arabic, built for Arabophone audiences with the Arabic intellectual tradition in mind. It’s also the solution to our bibliographical problems, essentially letting you browse online more effectively. It’s not perfect yet, namely in that it does not include every Arabic book ever written but each day, the catalogue becomes a stronger engine, as more data is added to it and as more people use it; it is often the first result you find when using a standard internet search engine to look for a text, like, say كتاب سيبويه, Kitāb Sībawayh. The cataloguing team has needed to expand multiple times to accommodate the work-load and under the direction of Mohamad Malchouch, it is full-steam ahead for the project. Here, we’ll be giving you an introduction to using the system, as well as a crash-course in cataloguing standards.

Everything began in 2001 when the IDEO decided to develop a digital catalogue in order to replace the paperboard one. At that time, there was no available software that could catalog in Arabic-script, not to mention recording the names of the authors (complete with different naming conventions shuhra, nasab, kunya, laqab, nisba, etc…), the Hijri dates or the relations between the works (i.e. commentaries, refutations…) So the IDEO decided to develop their own. Their main philosophy was that technology had to adapt to culture, not the opposite. The brain behind AlKindi is René-Vincent du Grandlaunay, IDEO’s head librarian since 1995. He worked with French volunteers to build the catalogue until 2011, then with a French IT company (2011‒2013), then with an Egyptian IT company (2013‒2015), then the IDEO hired its own IT team of Egyptian developers.

AlKindi works well because the IDEO, based in Cairo, is a library dedicated to the study of Islam; the physical library contains around 150,000 books and 1,800 journal titles. The IDEO party line says that the IDEO collection focuses on the pre-1000 AH period in Arabic, but if you ask anyone who works on the post-1000 AH period, they are being modest: the IDEO collection is extremely strong for that period as well. In other words, the catalogue only has to accommodate one intellectual body –the Arabic tradition– and can cater to that tradition specifically. The lucky users can then dip into a text’s intellectual iterations by clicking a few buttons and then filling out request slips. But like we said, plug the name of a classic text in the Islamic intellectual tradition into a search engine and it is likely you will get a link to AlKindi somewhere on the first few search pages. The Dominicans have said their goal is to eventually be the meta-data for every edited and published book in the Islamic tradition, feeding into search engines. So what you have – even if you don’t have access to the physical IDEO collection– is a bibliographic discovery tool. For many texts, this is a more efficient way of finding a text and the published texts linked to it than going to Brockelman, for instance, because this is a way of finding which primary source texts have been edited and published as critical editions, as well as the studies on that work in multiple languages. In addition, ‘authorities’ or individuals who write or publish texts can be connected to each other to display family and academic relationships.

Before We Get to How to Use AlKindi as a Bibliographic Tool: an Intro to Cataloguing Systems

If you are trained as a historian or an Islamicist, it is important to know, when it comes to describing books and manuscripts, there is a difference between a conceptual model and a data format. In some ways, because of how digitized manuscripts are increasingly essential to the work of Islamicists, especially right now, when the internet is a huge treasure trove of materials, we all need to be educated on meta-data and how it functions. For now, a brief introduction to different cataloguing standards.

Until 1998, the prevailing conceptual model was ISBD (International Standard Bibliographic Description). Created in 1954 by IFLA (the International Federation of Libraries Associations and Institutions), it consists of nine zones (0: media type, 1: title, 2: edition, 3: maps and electronic resources, 4: publication, 5: material, 6: series, 7: notes, 8: identifier). A complete ISBD may look like this:

0: Text: unmediated

1: A manual for writers of research papers, theses, and dissertations: Chicago style for students and researchers / Kate L. Turabian ; revised by Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, and University of Chicago Press editorial staff.

2: 7th ed.

3:

4: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2007.

5: xviii, 466 p. : ill. ; 23 cm.

6: (Chicago guides to writing, editing, and publishing).

7: Includes bibliographical references (p. 409-435) and index.

8: ISBN 978-0-226-82336-2 (cloth : alk. paper) : USD35.00.

Inside each field, the data has a specific format called MARC (Machine Readable Cataloguing), with sub-fields and labels. The aim of having a defined format is to facilitate import and export of data between machines. When properly tagged in a database, the fields and sub-fields are searchable. MARC was developed in the 1960s by Henriette Avram at the Library of Congress in the United States with the introduction of computing systems to information sciences. The advantage of such a system is how much data can be loaded into a single entry. MARC is the standard applied to North American institutional libraries, for example.

Another data format is EAD (Encoded Archival Description). Published in 1998, its purpose is to describe archival documents and manuscripts. Its focus is not the text (Kitāb Sībawayh) but the object (Milan, Ambrosiana, X 56 Sup.). Objects are unique (identified by a shelf number in a collection), texts are not (there are around a hundred manuscripts of Kitāb Sībawayh in the world). Another possible data format sometimes used to describe archives, although primarily developed for the electronic text edition is TEI (Text Encoding Initiative). The type of metadata usually encoded in the EAD and TEI formats is very rich from the ‘object’ perspective (material description of manuscripts, equivalent of ISBD zone 5) but indigent at the ‘text’ level (ISBD zone 1). An example of TEI you might have seen, especially if you have worked with manuscripts, is Fihrist, the union catalogue for Islamic manuscripts in the UK.

In 1998, IFLA published a new cataloguing model called FRBR (Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records), and in 2017, they launched the latest version called IFLA-LRM (Library Reference Mode). This new conceptual model is not a one-dimension model, like ISBD, but a four-level one, from the more theoretical to the more physical: Work, Expression, Manifestation, Item. Each level can be attached to a different authority, bear a different date, and be linked to other entities at the same level. If we consider Kitāb Sībawayh:

Work: al-Kitāb, authored by Sībawayh in the second century AH.

Expression: the scientific edition of Derenbourg in 1881‒1889.

Manifestation: reprint by Olms in 1970 of the 1881‒1889 Paris edition.

Item: offered to the library in 1989 by G. Troupeau.

As for the format of the data (here above, the data is not formatted), a new standard was published in 2010 called RDA (Resource Description and Access), which is specially designed for IFLA-LRM.

This new model is much more powerful than ISBD because it enables the recording of relations at each level. Kitāb Sībawayh, as a Work, has been commented, refuted, glossed, and studied, and this has nothing to do with the lower levels. So there is a Work—Work relation that is independent of whatever edition of the Kitāb is in our hand. This can be called a ‘horizontal’ relation at the level of the Work. This ‘horizontal’ network of relations represents the cultural history of the texts.

But in the same manner, ‘below’ this one Work by Sībawayh I can record the different scientific editions and translations. For example, in the IDEO’s library we have 3 manuscripts, 13 editions, and 6 translations of the same Kitāb Sībawayh. And of course, these Expressions are connected: Derenbourg worked on Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, arabe 3987, among other manuscripts, for his scientific edition. Again, at the Manifestation level, one given edition can be reprinted, photocopied, or digitized. One can thus consider that this ‘vertical’ links, from Works to Items, represent the editorial history of the texts.

Whereas MARC was never intended to describe manuscripts, hence the creation of EAD, IFLA-LRM intends to gather under one model both document types, manuscript and printed. There is an ongoing war in the quiet world of libraries between librarians and archivists. The former ones focus on texts whereas the latter focus on objects. IFLA-LRM wishes to gather both by integrating both logics in its model.

In 2011, right after RDA was first drafted, IDEO decided to reshape AlKindi in order to implement an online application to catalogue both manuscripts and printed books, according to the IFLA FRBR then LRM model, using the RDA data format. When scholars open our database AlKindi, they have access under one given Work to its manuscripts, editions, and translations (‘vertically’) and to all the others Works in relation (‘horizontally’). For example, in the case of Sībawayh’s Kitāb: 1 Work, 22 Expressions (3 manuscripts, 13 editions, and 6 translations), 29 Manifestations, 30 Items. And this Work is in relation with 232 other Works (commentaries, refutations,…), which in turn have been commented, refuted and studied (more ‘horizontal’ Work—Work relations), but also edited, translated and reprinted (‘vertical’ editorial history of each Work).We’re about to see how all of this data can help you gather bibliographic data.

What made the FRBR (later LRM) model so appealing to IDEO is that the library very often holds more than one edition of a given text, plus we wanted to record the relations between the Works, which is such a prominent feature in the Islamic heritage.

Using AlKindi as a Bibliographic Tool

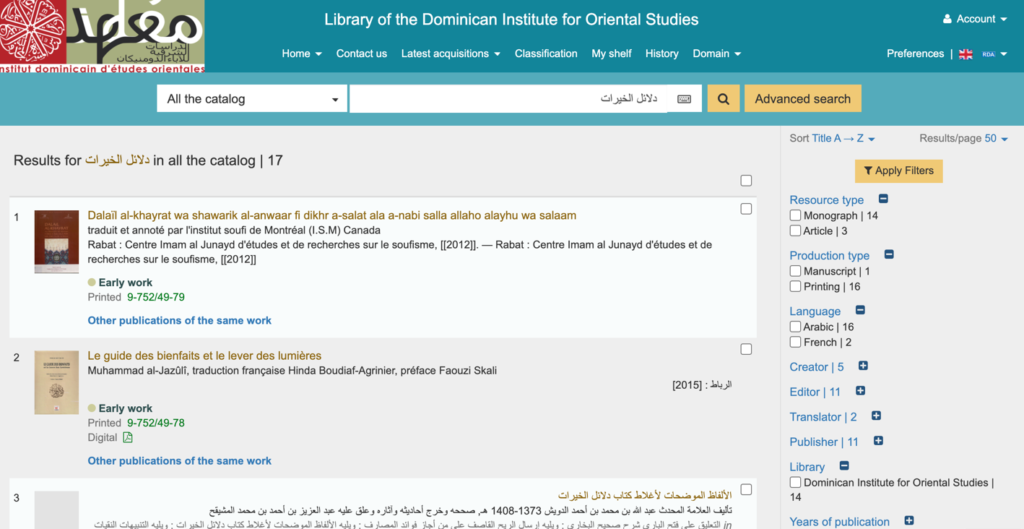

As with any catalogue, your use of it is going to eventually mirror your thought process and the nuances of your particular project. It is a case of playing with the software and getting used to it. However, there are some ways of getting started. We’ll switch from using Kitab Sibawayh and use the classic devotional text Dalāʾil al-Khayrāt دلائل الخيرات by Imam Muḥammad ibn Sulaymān al-Jazūlī to do the search. We’re looking for critical editions of the text, secondary sources in multiple languages, and commentaries on the text itself. Note we’ll be using simplified transliterated text for these examples.

Method 1: Go Directly to the Text you’re using*

- Search the title of the text you desire. Since the text is originally in Arabic, we’ll do the search using the title in Arabic script. The first result looks promising. We are going to click “Other Publications of the Same Work.”

- This takes us to a page dedicated to the work itself: it lists different editions, translations, a manuscript edition (shared with Maʿhad al-Makhṭūtāt), and relations to other works.

- Do note: if we had gone from the main page of the catalogue to an edition of Dala’il al-Khayrat, much of the data on these other publications would have been viewable on the right-hand side of the page.

*Do note that the policy of AlKindi regarding transliteration has recently been modified. By default, the IDEO encodes in the same alphabet as on the resource, whatever it is. If all the publications of a given author are in the Arabic script, the search engine would not bring any result in transliteration. But if this author has been edited, translated or studied and published in another alphabet, the IDEO will create the corresponding entry. Recently, because the IDEO now collaborates with the French National Library, we tend to transliterate more, including Work titles and author names, even if we only have them in Arabic script. Another rule is that the search engine brings only data in the same alphabet as the query, although all the data is connected in the database. The safest way to find exhaustive result is to search in Arabic script (also to avoid transliteration standard issues) and then move to the higher levels (author’s record, Work’s record). In IFLA-LRM terms, this means that the “All the catalog” result page only displays Manifestations in the very alphabet used in the query.

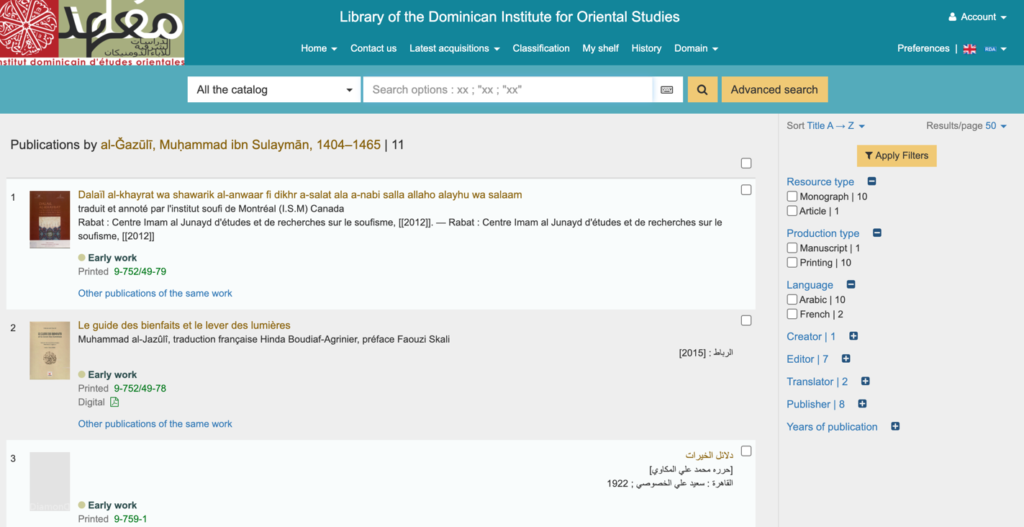

Method 2: Search by the author

- You can either search for the author’s name or look for a text they wrote, then click the author’s name. AlKindi tries to account for variant names, including different transliterations. We’ll search ‘al-Jazuli’, for Imam al-Jazuli, the author of the Dala’il.

- Searching al-Jazuli alone got us to a few secondary sources, in non-Arabic languages but that’s not what we want for now (see below for a note on how IDEO handles transliteration). We’ll bookmark a few of the search results for later, notably those by Hiba Abid.

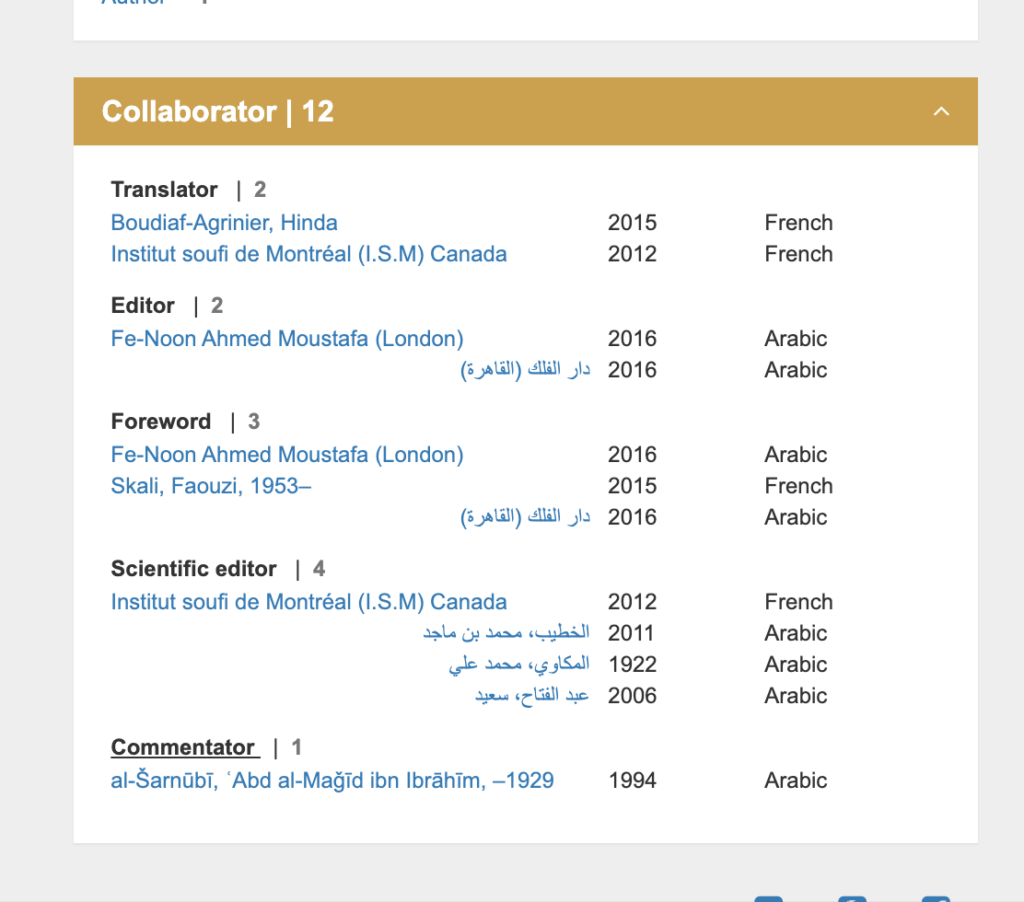

- We’ll try again with the Arabic al-Jazuli الجزولي. We were more successful so we clicked an entry. This is a translation of the work. Then we clicked al-Jazuli’s name in the entry in the ‘Explore’ Box.

- The author’s page lists the authorities in the tabs on the left—hand side: note that you can see Variants under Access Points.

- The author’s page is also useful for the Collaborator section. This lists anyone who produced work linked to the primary author.

- However, let’s go back to finding Dala’il al-Khayrat. We click through to ‘Publications by this Authority’ and in a separate tab, clicked publications On this authority, since we’re looking for secondary sources as well. We’ll focus on Publications by This Authority’ for Now. This took us back to a summary of catalogue entries. Since al-Jazuli was known primarily for this text and it is extremely popular, all of the results are related to the text. Here, I could find different critical editions of the Dala’il that I can use in a variety of ways (i.e. tracing the publication history, weighing critical editions against each other, etc). This is also a way of finding commentaries on the text (see Method 1).

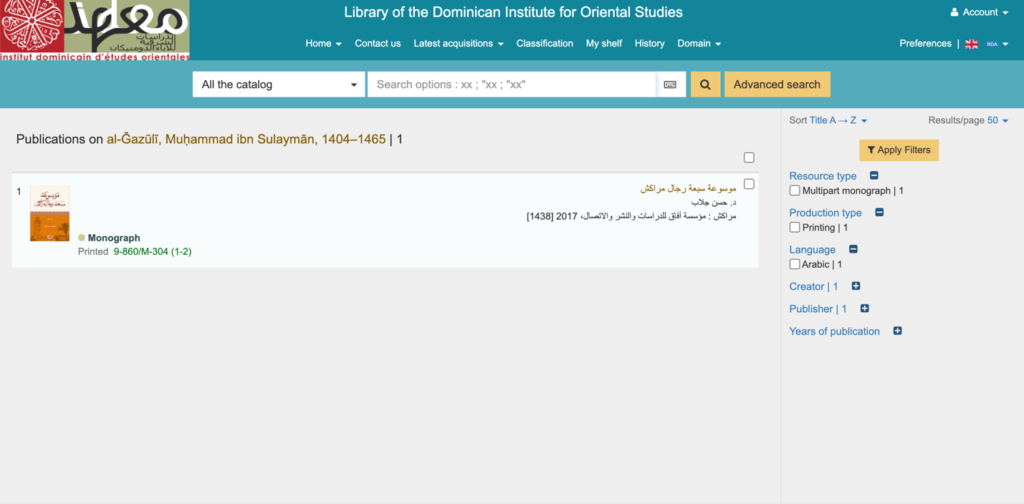

- Recall we also, on the page for al-Jazuli, clicked the ‘Publications on this authority.’ This has led me to a great find: a secondary source in Arabic on men from Marrakesh. I can use this to fill out al-Jazuli’s biography, in addition to obviously filling my knowledge of the historiography of al-Jazuli in Arabic.

Further tips

- Check here to see what resources exist for critical editions and open-access sources. A word of caution: we have listed several for Arabic and Persian that do not respect the rights of critical editors. Try to acquire the books via programs that respect copyright and the rights of editors.

- You can use AlKindi in a similar way to do work on manuscripts and book history. If you can find commentaries on a text using the AlKindi catalogue, you can then take those titles and apply them to manuscript catalogues, online manuscript collections (we recommend starting with Evyn Kropf’s guide to online collections), and al-Furqan’s search engine.

- Make an effort to cite the AlKindi catalogue where you can and thank the team for their work by mentioning their names, which are all here.

- Because IDEO understands the researcher, they also apply a classification number to each article in an edited volume: they turn up in keyword searches as well as individual items, like in the example below.

- You can use AlKindi in conjunction with other catalogues, including your home institution. Because the IDEO is based in Cairo (and particularly because they spend an immense amount of time each winter at the annual Cairo Book Fair updating their collection), they have an excellent collection of monographs in Arabic; they also subscribe to many Arabic-language academic journals. So AlKindi can be used to see what monographs exist, especially because you can see how the primary source texts you study are connected to monographs and journal articles. You can then request them from your home library or put in a request they order it or subscribe to the journal. It also, as you may have noticed, makes looking for Arabic secondary sources easier because of how the linked data functions but also because the IDEO collection is so good.

AlKindi and the future

In the future, the IDEO wishes to distribute AlKindi to more libraries specialized in Islamic studies, and manuscript libraries in particular. So far, three libraries use it, in addition to the IDEO: the Arabic Manuscript Institute in Cairo, the Giorgio La Pira Islamic Library in Palermo, and the French Archaeological Institute in Cairo for its manuscript collection. Negotiations are underway with the Vatican Library for its Arabic manuscripts.

On the technical side, the IDEO is also planning to integrate two more features of the IFLA-LRM model in Diamond, the software that builds the AlKindi database: Manifestation Aggregates and Subjects. These are technical issues but they will facilitate search and connection with other catalogues.

In the end, AlKindi will probably not become the “Google for Islamic texts” 😉 but if developed properly with the Semantic Web and the international identifiers for authors and works in mind, AlKindi can greatly contribute to simplifying the life of Islamic scholars through tools as simple to use as Google Search.

Jean Druel is French and lives in Cairo. Since October 2014, he has been the director of IDEO. He completed a PhD thesis in the history of Arabic grammar under the supervision of Pr. Kees Versteegh (Nijmegen, 2012). He is currently editing the manuscript Milan, Ambrosiana X 56 Sup. (Sībawayh’s Kitāb).

N.A. Mansour edits Hazine.