The digital exhibition had been introduced to the cultural heritage scene before the pandemic, but since Spring 2020, it’s here to stay, in part because of the accessibility of the form and in part, because increased familiarity with digital curation has allowed students, independent researchers, and others to partake in carefully bringing together objects and pairing them with one another. However, very few, if any, have tackled a digital exhibition exploring scent. That’s the challenge the curators of Bagh-e Hind, Bharti Lalwani and Nicolas Roth, have set themselves. The exhibition explores 17th and 18th century India through both the lens of scent and the garden: each exhibition room is based around either rose, narcissus, smoke, iris, or kewra, featuring not only paintings where the scent is part of what is being communicated, but poetry in translation, other objects related to those scents, and the curators’ notes, so we can follow along behind the scenes.

As Bagh-e Hind represents the collaboration between an academic and a perfumer (who is also an art critic), it sits nicely at the nexus of the communities Hazine is trying to cater to. Beyond simply documenting the curation of such an exhibition, there’s also something intriguing about the history of olfaction, which is often thought of as elusive: yet, Lalwani and Roth bring together multiple wells of knowledge to allow us to smell the past and challenge our ways of knowing.

What are the origins of the project? How was the initial idea conceived?

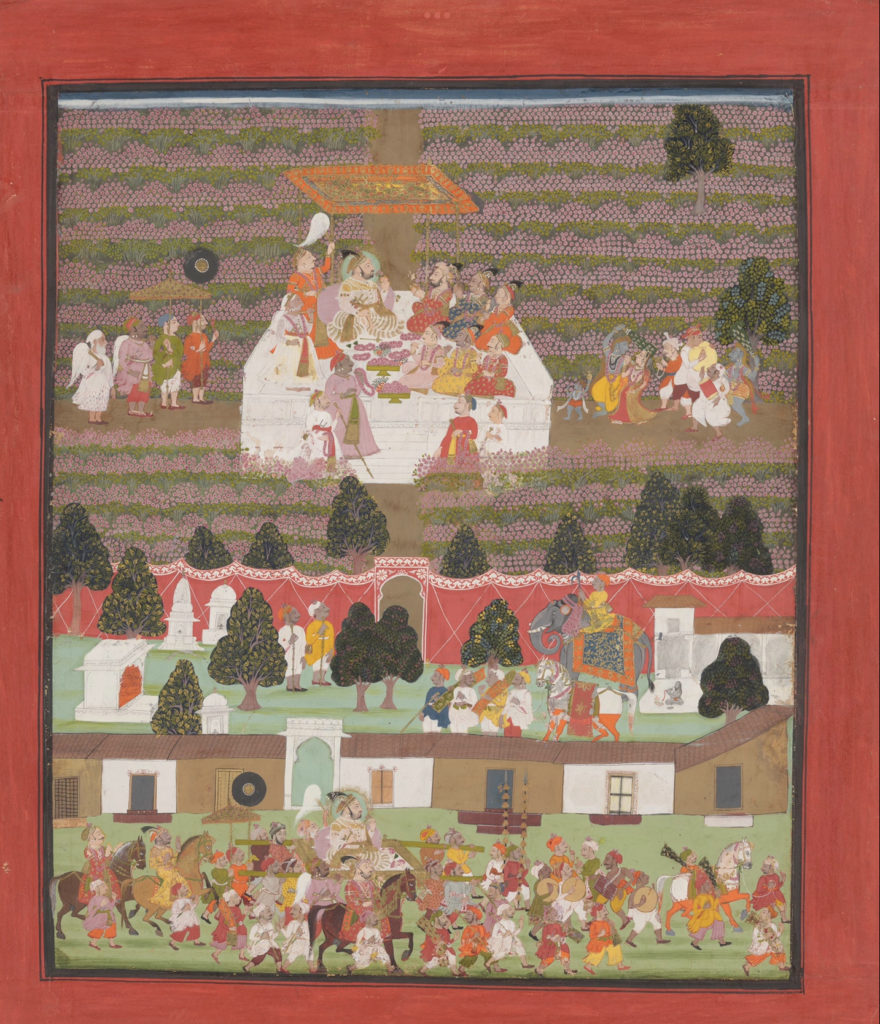

Bharti Lalwani: Bagh-e-Hind first took shape in 2018 as a fragrance translation I created of a 17th century painting The Emperor Shah Jahan with his Son Dara Shikoh, a folio from the Shah Jahan Album, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. It was not the subject of the folio itself but the flowers, trees, clouds, birds and insects painted into the frame that immediately made me think of notes and flavours of honey, frankincense, mango, peach and jasmines.

The fact that such paintings, while bursting with olfactive prompts, have not been recontextualised with tangible scent translations, was puzzling to me. I thought about exploring this in depth with a historian who would anchor the concept to the context of this period. Last year, around May 2020, I came across the recent work of gardener-scholar Nicolas Roth, whom I then extensively interviewed for my Journal. In May 2021, after reading much of his published work and having put my own ideas of synesthesia to the test, I extended an invitation to him to partner with me on Bagh-e Hind to explore, refine and present these concepts in a cohesive manner.

It appears straightforward but for readers I would like to contextualise the spark for Bagh-e Hind: By late 2017, I made the decision to exit the contemporary art and academic scene. These are highly entrenched systems that repeatedly reward mediocrity while feigning scarcity of opportunity. My own temperament as an independent critic blisters against such machinations, so I set out on a new path to create opportunities for myself in a horizon beyond constraints and (financial /emotional) exhaustion.

Bagh-e Hind came together between June-September 2021 with a self-funded production budget of $600, of which approximately $350 was spent on sourcing perfumery ingredients, commissioning handcrafted glass perfume bottles, incense and acquiring a small number of vintage objects. The rest was spent on shipping perfume and Edible Perfume™ samples to Nicolas in three lots. There are other running costs that continue to add to this budget. Bagh would have cost a lot more were it not for my patrons who generously sent me samples of Narcissus extract, ethical Mysore sandalwood oil, and so on.

By funding this project myself, I ensured that in the process of building this space of beauty and wonder, both Nicolas and I remained autonomous, free to take our concept in any direction without fear of being censured, co-opted or neatly reduced to our identities. The sale of Synesthesia artworks produced for this exhibition, or sales from my own perfumery practice, funds the honorariums for essays produced by contributors to our curatorial catalogue. It may have taken three years to gather the resources and wherewithal for this exhibition but ultimately it is the goodwill that I have cultivated over the past decade that now accelerates this project’s ambition.

How did you distribute labor between the two of you?

B: While our vision for Bagh-e Hind is shared, the design, production, press and publicity remain in my purview. Nicolas on the other hand has shaped the botanical and art historical dimension of this project. Apart from our dialogue on painting to perfume and flavour notes, published in each of the five chapters, his curation of paintings, photographs of garden sites, and translations of Urdu poetry from this period breathes life into the project.

As we continue to expand the scope of our collaboration, I still marvel that such an extraordinarily sensuous exhibition can manifest through the contrasting minds of two individuals who did not know one another at the beginning of this project, exist in entirely different contexts and have never met (except virtually). Our partnership is no doubt unique in the way we combine facets of early modern South Asia, olfaction, art and literature. However, I know of only one such example that set a precedent for us — the collaboration between historian James McHugh and master-perfumer Christophe Laudamiel in 2008 to create scents based on McHugh’s research on aromatics and perfumes in pre-modern Indian culture and religion. While Laudamiel is one of my key mentors who in fact sent materials such as narcissus extract for this project, McHugh was one of Nicolas’s dissertation research advisors — a detail he happened to reveal much later into our project. I thought it a very fortuitous coincidence and we are very lucky that Bagh-e Hind receives their support and confidence.

This collaborative process, for me though, has not been without its challenges. In the course of working together in this remote manner, I have at times felt that our creative and academic worlds were clashing, our expectations out of sync with one another. But Bagh would not be the scintillating exhibition that it is if we were not honest and compassionate towards each other – the historian did not let me make mistakes and I am full of praise for the ethics he has brought to the project.

Photo credit: Nicolas Roth

Nicolas Roth: I would say that Bharti also frequently provides more daring creative impulses, pushing us to think of new concepts and modes of presentation to communicate our research and creation to different audiences on- and offline. At the same time, and as this is an ongoing conversation, my concern has been that the elements we incorporate –from the paintings and other artworks we feature to the plant species we discuss, the fragrance notes we incorporate in products, and the poetry we use to contextualize both paintings and botanicals –are both historically accurate and cohere with both of our aesthetic visions; what Bharti refers to as the ethics I have brought to the project. However, another way in which I think our collaboration has been particularly fruitful, harmonious, and enriching –at least for me! –has been on the level of the aesthetic, that is the development of the visual and olfactory output that constitute the primary ways in which our audiences experience Bagh-e Hind. Decisions as seemingly minute as how to cluster paintings and images of flowers on the website were worked out in mutual consultation, and the smells and tastes tweaked based on both our verbal discussions and my responses to the samples Bharti would send me, until everything just “fit” – and if it does not for one or both of us, we keep developing and exploring it further.

While, as Bharti has noted, we come from such different backgrounds and contribute different areas of interest and expertise to the project, we have been continuously discussing, listening, and learning from each other in creating the look and smells of our “garden.”

The exhibition includes poetry and music, as well as visual art. Tell us about how you both approach intermediality and how that plays into the world of scent.

B: As I designed the exhibition-galleries, I grew steadily ambitious: I wanted the audience to gasp, I wanted to take their breath away as they browsed each chapter. But how was the viewer to smell and taste my craft, while Nicolas’s selections of paintings and flowers were more straightforward to delight in?

The answer was poetry: it would supplant the seductive language I was already employing to describe the fragrance and flavours being created. To put it crudely, I wanted to embed “hot poetry thirst traps” across the exhibition, smouldering so discreetly so as to take the audience by surprise.

Midway through our collaboration, the substance of this poetry became a bit of a sore point between Nicolas and me. He was concerned with finding just the right verses in terms of time period and botanical references. Meanwhile, I couldn’t help feel that what scholar and translator Frances Pritchett describes as “sex, drunkenness, madness, death” the smell-language-embers of the late Mughal world, were missing in our exhibition, especially in Chapter 2, Narcissus, which is resplendent in erotic-romantic, sacred to sacrilegious subtext. Finally, around August, we gave Frances a preview of Bagh-e Hind where both she and Nicolas patiently explained to me that the poetry of the 17th and 18th century is substantively different from the later verse of, say, Ghalib for example – which would not be an appropriate fit.

The internet is already a cold space. The last thing I wanted to do was build an online exhibition that was tame, bland and one-dimensional. Throughout the process of crafting Bagh, I functioned as a hyper-efficient spider weaving several complex webs at once. I constantly dismantled ideas, assailed them from all sides, then rebuilt them with an added edge. Hence, I stressed on the inclusion of poetry that could add fiery sensuality as transgressive cues to the nuanced yet stunning visual material. So, much to the irritation of my co-curator I’m sure, I kept probing ways to subvert the sweetness he steadily brought to the show.

If that all sounds intense, then the classical Hindustani music that Berkeley-based architect Uzair Siddiqui selected to match each painting, perhaps heightens the atmosphere of our collaboration that allows viewers to experience the depth of its salty-sweet flavour. The scores for Painting 2 and 5 are especially evocative, as are the selections of poetry that Nicolas eventually curated into our garden.

N: When Bharti raised the excellent idea of incorporating poetry in the project, my primary concern was that it would make sense relative to the artwork – in terms of time period and themes – and the plant species our project highlighted. I have stuck to Urdu poetry from the 18th and very early 19th century so far, before the sociopolitical changes and colonial censure of the 19th century began to subtly but fundamentally change the outlook and thematic focus of the tradition. At some point, I might also bring in Indian Persian poetry from the 17th and 18th centuries, which would have been an essential component to the cultural environment in which “our” paintings were originally created and viewed, but which is at an even further remove for most contemporary South Asian audiences than historic Urdu verses. Part of the challenge in using this material in a project like ours is that the full aesthetic impact often requires considerable literary context to be appreciated. As a result, just how clever, evocative, or racy a verse really is may not be apparent without considerable knowledge of the tradition – and selecting pieces that would immediately read as sensual and transgressive to a contemporary audience the way Bharti envisioned was not a straightforward undertaking!

B: I would like to add that our collaboration has granted me –and by extension, the public–the keys with which to access the abundant olfactive cues embedded in 17th and 18th century paintings. Our conversations have certainly expanded my appreciation for the poetry of this period – and how painting and verse ought to be viewed in parallel, keeping close attention on the elliptical use of flowers, their form, colours and significance.

What consideration did you take into mind when building the exhibition website? Was anyone else involved?

B: While I am not tech savvy, I had some experience building Litrahb Perfumery by early 2021 which contains sumptuous visuals and a Journal that communicates my research in a clean, jargon-free format.

However, building an online exhibition requires better software and I was painfully aware of the lack of sophisticated tools that would allow one to satisfactorily enlarge paintings. So we circumvented this: while each painting in this exhibition, and even most of the objects can be magnified up to 300%, they are captioned with their source link so audiences can go to the institution-site to explore further. One more note to add is that our exhibition creatively comes together with objects and paintings from museum-vaults, majority of which are not on display, while legitimately avoiding the high image licensing fees they charge. I had to write to at least two major museums to ensure permissions for digital use were free and fair for public access.

N: Where possible, we also tried to use images from the Stuart Cary Welch Islamic and South Asian Photograph Collection, a remarkable body of free-to-use images of art and architecture made available by the Harvard Fine Arts Library. I have been contributing to its ongoing digitization as a researcher and cataloger for the last couple of years, which is in fact how I first encountered several of the artworks that now form part of Bagh-e Hind. That being said, responses from museums whose works we feature, insofar as we have received any, have so far been positive as well.

I also admired how the digital exhibition format allowed you layers of accessibility not afforded to all in-person exhibitions: it was (ironically) scent-free and you could view it at home anywhere in the world at no cost, critical in a world still in the midst of a global pandemic. How did you both approach accessibility in building the exhibition?

B: I have seen some well executed exhibitions across Southeast Asia, China, South Korea and the Middle East between 2008-2019. I have also had excellent mentors in this field who have sharpened my outlook: I learned from their practice in order to strengthen the format of Bagh-e Hind that can now go from digital to phygital iterations over the coming years. Two aspects were crucial for me: The intellectual and aesthetic splendour of the exhibition and the curatorial catalogue. My blueprint is Negotiating home, history and nation: two decades of contemporary art in Southeast Asia, 1991-2011. Apart from the fact that this catalogue included several comprehensive research essays and one short story by Malaysian novelist Tash Aw, this was in fact the first exhibition I saw in 2011 that forced me to unlearn my training in western art history/theory, and to look instead at Southeast Asian contemporary art on its own terms within the ambit of its own history, culture, religion, and politics. I expect our catalogue to take form over the coming year as I have commissioned Nicolas and other critics and perfumers to contribute essays on a range of fragrant subjects. Nicolas and I have also compiled an unusual Reading List concerning gardens, scent, perfumery and flavour.

Ironically, I got to build this exhibition at a time when everyone globally has moved online, so I had complete confidence in building a digital sensory show that would be well received. I also wanted to treat this with all the seriousness of a “museum” exhibit. I thought – if everyone was now bound to experience art online, then was there a difference between viewing a virtual collection of paintings on the Met or on Bagh-e Hind?

So, I went further. As any museum would, I planned an online VIP Opening Night on 10th September 2021. Incense from our exhibition with handwritten invitation-notes reached most of our international guests of honour in time so they could arrive at the opening with tangible scent references. Our event included a narration of a fragrant Urdu qissa, love story, by academic Pasha M. Khan. Neha Vermani shared her novel research on food practices during the Mughal period; I gave a quick curatorial tour and Uzair spoke on the significance of the classical music he had chosen to match each painting. I then invited responses from our guests among whom were Frances Pritchett, Dipti Khera and James McHugh. Maybe the presence of some minister for a virtual ribbon cutting ceremony was the only thing missing.

As if all of this effort was not enough, I have been offering curatorial strolls through our Bagh, just as any museum curator would. I offer my time to academics, journalists and cultural producers to give them access to aspects of the show that would otherwise remain invisible. The general public can book a sair with me via the Gift Shop – oh yes, I also devised a Gift Shop like a proper museum. So there are many ways the public can actively show their support for Bagh-e Hind.

I love conducting these tours because it gives me a chance to connect with my audience while offering them insight into, among other things, the general behind-the-scenes of how perfume is made, and how the opaque fragrance industry still retains an orientalist lens. I treat each tour as a thought-experiment; I have under two minutes to hook my audience in and earn their admiration. Each time it is a thrill to see my guests going away thoroughly inspired, full of awe, fire and wonder!

N: For me, Bharti’s vision for a virtual exhibition was exciting especially because of the opportunity it provided to bring early modern Indian paintings in direct conversation with both their art historical context and with the material culture they reference in a way traditional museum shows rarely do. We were able to virtually bring together works held in collections around the world, presenting each painting that we translated into scent among a cluster of works representing the same genre and theme, illustrating both patterns in Indian painting and the cultural significance of the olfactants they feature. Similarly, we could pair each set of paintings with a gallery of photographs –most of them by me, many from my own garden– of the exact plant species and varieties featured in the paintings. We were also able to add music representing the rāgas and rāginīs or Indian musical modes figuratively represented in many historic Indian paintings. Altogether then, the virtual format has in some sense allowed us to create a more comprehensive and immersive experience that does not present individual artefacts in isolation but invites the viewer into a whole web of art, plants, scent, sound, poetry, and so on.

The inclusion of smoke as a scent in this exhibition was really inspired. How did you decide which scents to include?

B: I was quite delighted by Nicolas’s essay Verbal (Re)constructions: Reading Architecture in the Urdu Masnavī. Our agreement was that the selections of the five paintings for this project would be left to him. But I have hilariously meddled at so many points in this process, in particular for Smoke and Kewra. While his essay discusses codified architectural idioms in Mughal and Awadhi paintings and long form poetry in the 1700s, my eye –and nose– were drawn to the various illustrations of fireworks in the paintings he chose to accompany his essay. I instinctively knew that Smoke would be a genius concept to play with as it would challenge audience-perception of what a “Mughal garden scene” could smell like on a night of festivities. Instead of highlighting floral notes, the smokey notes of pink pepper, patchouli, vetiver, cedarwood and iso-e-super sparkle and hover over the receding indolic fragrance of night blooming flowers such as tuberose, jasmine and honeysuckle.

Apart from the perfume translation, the synesthesia iterations were a joy to conceptualise! I’ll let Nicolas say more about the ‘Smoke’ perfume and flavour I created from ambergris, black cherry jam, tonka bean, cocoa, spice and menthol crystals that pairs with the Indian Monsoon Malabar Coffee, and the camphor incense included in this Synesthesia Box.

N: When Bharti first asked me to select the original five paintings at the heart of Bagh-e Hind and explain their olfactory references so as to develop scents based on them, her only request was that one of them should be a work featuring fireworks, which I thought was quite brilliant. Smoke is such a complex smell element –from the sulphurous, acrid fizz of firework smoke to resinous sweet incenses like aloeswood and frankincense– and quite ubiquitous in early modern Indian paintings and literatures. Nonetheless, it does not really enter into the way people generally “read” paintings or gardens today, even though Bharti’s scent and flavor creations make abundantly clear just how vivid, evocative, and rich a part of our “smellscape” smoke is. The “firework smoke” flavoring Bharti created is one of the most striking elements of any of the Synesthesia Boxes she has created. As soon as it hits the tongue, whether as edible perfume powder by itself or in the corresponding coffee, one immediately gets a bright, titillating, slightly metallic and slightly acrid sensation of firework smoke, unmistakable and fully realistic yet pleasant. The camphor incense supports this same effect, yet in a perhaps even more playful way, since in the case of incense, smoke itself is the medium through which fragrance is delivered. There is thus already a smokey note to incense as it is, yet the metallic-medicinal brightness of the camphor subverts one’s expectations of what exactly that smokey odor is.

If your audience could take one thing away from their visit to Bagh-e Hind about scent and smell, what is it?

B: Defiance. This project emerges from my refusal to be erased while opting to chase pleasure instead. In fact, our garden cedes pleasure to the audience, an indulgent daydream where weary minds can rest on abundant beauty or slowly meander between fragrant parterres of the past and the present. Bagh-e Hind is an invitation to viewers to fall asleep beneath the flowers.

N: How central plants and aromatics were to the lived experience, arts, and aesthetics of people in the not-too-distant past. I think Bagh-e Hind really asks audiences to think through the materiality of the (idealized) worlds imagined in early modern Indian painting, and to viscerally experience aspects of that world through senses –smell, taste, hearing– that we do not usually utilize when responding to the visual arts. In doing so, I think it also highlights the importance of the “details” that encode these sensual references in the paintings, the intentional evocation of moods and sensory memories, apart from questions of ideological import, stylistic development, or technique that have more commonly occupied scholars.

Whether in trying to understand paintings or poetry, knowing the correct flowers and fragrances, their uses and associations is not trivial. Rather, it is essential to how these artworks were conceived and meant to be experienced, to what makes them meaningful. To put it differently: a painting of two young aristocratic men holding flowers while sitting on a terrace like the one that is the starting point for the ‘Narcissus’ section of Bagh-e Hind, for instance, might just seem a pretty picture, but it gains layers of meaning when one knows that the flowers are narcissi, painted with botanical accuracy and precision. If one knows these flowers, one knows that they have a fresh, sharp fragrance – a fragrance which in early modern Iran and South Asia was considered an exhilarant that “opened” and invigorated the mind and strengthened one’s respiratory system and sense of smell. On that level, then, the purposeful depiction of the narcissi points towards excitement, stimulation, and intellectual activity; the two young men are elegant, cultured, and consciously preparing to engage in sophisticated repartee and perhaps more.

Moreover, if one is familiar with the symbolic language of Persian and Urdu poetry, one would immediately associate the narcissus with eyes – to which they are traditionally likened due to the shape of the flowers – and vision, an association which evokes amorous glances and longing, as well as the desire to (visually) consume and comprehend, underpinning the mental acuity and inquisitiveness meant to be supported by the flower’s fragrance. The floral and olfactory element of the painting is thus in fact far from coincidental, but highly deliberate and key to the scene the painting is intended to convey – a scene that is far more complex, sensuous, and titillating than a cursory viewing of the painting might suggest.

The exhibition includes your notes as you discussed the exhibition and development of the scents. What motivated you to draw back the curtain and let the audience know about your curatorial and collaborative process?

B: This was deliberate on my part as I wanted the audience to understand the dynamics of our unique collaboration. All through our process, we exchanged notes regarding the contextual matter of the paintings and the corresponding fragrance translation. This meant sometimes devising inventive ways to communicate with Nicolas about the sense and scent of a garden-site. As a perfumer, I am unusual in the sense that I work with floral extracts while having no clue what fresh bouquets of narcissi, violets or iris smell like as I have never encountered them. So I have to rely on the gardener-scholar’s description of the fragrance of fresh blooms!

Nicolas’s expertise is on plants, and mine, on plant aromatics, which is what makes our intellectual and artistic pairing so perfect. His specificity of smell-descriptors led me to narrow down on the appropriate aroma chemicals. Take for instance Painting 4 which depicts a garden scene with no obvious floral notes, except faint smelling iris and poppies. Among the first batch of samples I sent him, I included a vial of perfume as a suggestion for this painting. Once he had a tangible reference, we could focus on what the olfactive notes should not be. I then created a questionnaire for him to which he could respond with a yes/no or pick a number from a scale of 1 to 10 to gauge the temperature of the painting. This helped us agree on notes of iris, orange blossom and cedarwood, which more than met his imagination.

As curators, it is our responsibility to gently guide audiences through our premise and process, to demonstrate how our decisions were based on deep understanding of our respective intellectual spheres without overwhelming them with too much informational text.

I want to add a note here about how insidious the function of smell is. This process reminded me of my days in Singapore where racial hierarchy is a social, political and economic tool that plays out in the minutest of ways. As a brown person, I would be warned by landlords that I was not to cook “smelly curries” that would offend my (Chinese) neighbours. That smell reflexively brings to the surface, unguarded, an individual’s biases, preferences and prejudices is intriguing to me. In this vein, our collaboration certainly brought up my own irrational loathing of the Kewra-note which led me to resist Nicolas’s selection of Painting 5. I even asked him to pick a different painting but upon some mulling, the source of my contention appeared to not be the actual extract itself but the synthetic kewra perfume which I had to employ as the prominent base-note: sharp, cloying, cheap-sweet, an all out assault on my senses.

The natural extract possesses a pleasant soft-sweet-milky note, and as Nicolas showed me, was praised by Babur in his memoirs and described as superior to animal musk. The only reason to use the synthetic version in perfume is because the natural attar is in fact a skin irritant. But this exchange made me think about how the historian and I should expand Bagh-e Hind with new research material to illustrate how and why such a rich and luxurious botanical lost its lustre over the centuries, as in present day it is used primarily as inexpensive food flavouring that sits, barely used, at the bottom of the ingredient hierarchy in contemporary (Euramerican) perfumery. I would like to flip this narrative with new fragrant compositions with historical references that Nicolas brings for us to explore together. The common confusion between Pandanus amaryllifolius native to Southeast Asia and Pandanus odorifer (kewra) native to South Asia also amuses me.

To return to the point about the potency of smell explored through our months-long collaboration, the historian and I have revealed ourselves to one another throughout our process whether we intended to or not. For instance, Nicolas’s responses to each perfume I produced tells me plenty about him. The scent-translation of Painting 4 being his favourite, additionally informs me of his exquisite (and expensive) taste as this formulation contains two of the most rare and precious perfumery extracts, orris and costus. On the other side of this, he has held, inhaled and tasted my brain and heart.

N: I would add that the creative exchange throughout this project is such a rich site of learning and reflection for both of us: not just regarding the other’s respective technical expertise or associations with a particular smell and the roots of those associations, but also the possibilities and limitations of communicating with our audience through scent and aroma in different media –perfume, incense, soap, food, drink, etc–and what it was that we were aiming to get across in any particular instance. Our different responses to particular fragrance ingredients and sometimes varying emotional associations with the finished scents highlighted the unpredictability and importance of individual experience in the reception of this art form. I think this enriches Bagh-e Hind tremendously, because it allows for members of our audience to have entirely new associations and experiences beyond the already rich tapestry Bharti and I have woven. To this end, too, I think it is essential to the project that we share our working notes, because they do not only reveal us –my instinctively expensive tastes in perfume! –and our collaborative process but should also serve as inspiration and a point of access for others to partake in Bagh-e Hind more fully.

How has the project been received? Do you have a sense of what kind of audience is enjoying the exhibition?

B: At our first curatorial meeting with potential collaborators in July, I found myself repeatedly asserting that this exhibition was not for academics but for the general public. I find academia extremely frustrating, a space full of constraints where everything needs to be quantified and drained of its colour! Whereas I thrive in an abstract landscape of dream, play and exploration that requires a degree of flexibility and agility in thought. If Mughal folios depicting fireworks were “common” (to academics) – so what? The public has not seen this prolific genre of paintings, much less experienced them in the context of sound, poetry, fragrance and flavour. We ought to bring out more of such paintings and objects for audiences to experience in imaginative ways.

Bagh-e Hind is a highly original concept that certainly possesses whimsy but it is not frivolous. Certainly historians have been translating perfume-related texts of this period but as far as I knew, no one had made the connections to contemporary perfumery practices, or conceptually linked “edible perfume” to the art, botany, poetry, literature and material culture of the 17th and 18th century all at once. My own attempts in 2018 to locate a historian who would treat these ideas seriously and be willing to partner in earnest, without devaluing my intellect and labour, were unsuccessful. So, while I guarded the concept closely over a few years, I realized the odds of materializing Bagh-e Hind were already stacked high as it not only challenged but ventured well beyond established narratives.

My initial anxieties about how such an unusual exhibition might be received drove me to not only double down on the premise but also to test it rigorously among my network of scholars, museum curators, exhibition designers, one scientist and a perfumer, who gave me their responses through July and August. Considering I had the added responsibility of presenting the historian’s research with the respect it deserved, I functioned as a critic-on-the-offensive to buttress the concept and ensure the presentation was impeccable and unassailable. I may even think of Bagh as a provocation: a contestative space full of radical ideas of love and pleasure that lays siege to the anosmic academic approach.

I am much more relaxed since the show launched on 10th September 2021 and am thrilled to see everyone, academics and the general public, gushing about the show.

N: Beyond the outpouring of overt praise and interest in the project that we have been so fortunate to receive, we have also noted that aspects of the subject matter of Bagh-e Hind –scent and flora as a an aspect of history or a lens through which to approach Indian painting, for instance–already appear to be taken up or at least acknowledged by scholars and creatives much more than we used to see before the launch of our website. It often is impossible to say whether this was directly our doing, of course, but I would like to think that we are at least contributing to this novel interest in things floral and fragrant.

What projects are you both working on, separately or together, that we can anticipate for the future?

B: First, let me say that ours is a garden that invites pollinators. I love the enthusiasm with which curators have reached out to encourage us to propose exhibition concepts so we may draw this project out into physical spaces. Considering the stressors of the past year, institutions seem more willing to engage with fragrance and the need to reconnect with nature. I, for one, wish to view Bagh as garden-pavilions in multiple cities; so I would ask curators of garden museums, botanical spaces and even university-libraries to get in touch with us!

We are working with the Institute for Art and Olfaction in Los Angeles, for instance, to bring Bagh-e Hind to their gallery in tangible form in July 2022. By November 2022, Bagh will also appear in some form at a major museum in the US, but I would like to emphasize we are keen on working with smaller institutions and universities. I have compressed Bagh to such a point that it can exist on a shelf or it can be expanded with such opulence to occupy an acre of garden space.

Apart from developing proposals, I continue my exploration of Edible Perfume™, Perfumes by the Season, and soap as a means to experience an architectural and historical artefact. One of my latest soap-projects that has been a year in the making reflects on the form of a Rajasthani stepwell. I am also frequently commissioned to create fragrances for contemporary art exhibitions that gently shape audience perception and experience of the art. In the coming year, my aim is to understand how advanced smell-technologies enable diffusion of scent in the safest way possible, especially within a museum space where fragile objects are on display.

N: As regards Bagh-e Hind itself, my forthcoming curatorial essay will discuss in greater detail the plants and plant materials that appear in the paintings in the exhibit and their cultural and historic significance, including how they relate to the period’s literary culture as represented in the poetry selections included in the project. Moreover, I will be adding a reading list for anyone interested in more on the history of gardens, plants, and scent in medieval and early modern South Asia, which will hopefully also be a resource for other scholars adding to this field of study. For those specifically interested in the horticultural side of things, there will also be an annotated list of plant species and varieties that defined the period’s horticulture depicted in the paintings we feature and which they might want to grow.

Beyond further additions to the project itself, Bagh-e Hind has inspired some new avenues of research. For instance, it has brought me back to investigating a category of early modern Mughal preparations that seem to have straddled the boundary between medicine and recreational stimulant, perfume and food. Made primarily of aromatic substances and spices and sweet foodstuffs like nuts and honey, sometimes with the sumptuous addition of gold leaf and ground up precious stones or pearls, these mufarriḥāt or “exhilarants” seem in some sense like precursors to our edible perfumes, and suddenly make a lot more sense in light of the latter.

I am also currently working on various other research: contributions to two projects of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (one on histories of soil and the other on the Hortus Malabaricus, a monumental illustrated flora of Kerala published in Amsterdam between 1678 and 1693) as well as pieces on the cultivation and cultural importance of grape vines in the early modern Deccan and Indian visions of Afghanistan under the Mughals.

Returning to our current project, however: as Bharti has so eloquently said, our garden invites pollinators; that is, we are happy for it to inspire others, be they artists, researchers, or any other type of creative practitioners, to further explore the materials, artefacts, and histories it touches upon, and produce their own original work to contribute to both our knowledge and our enjoyment of this subject matter.

Bharti Lalwani

Nicolas Roth

Bharti Lalwani is an art critic and perfumer. Find her on Instagram.

Nicolas Roth received his PhD in South Asian Studies from Harvard University. His research explores the history of gardens and horticulture in early modern India, as well as the material and intellectual culture of the region more broadly. He draws on materials in Persian, Sanskrit, and various forms of Urdu and Hindi as well as painting and other art forms. When not reading 17th- and 18th-century South Asians’ accounts of their gardens, he can usually be found trying to grow what they were growing. Find him on Instagram @nic_in_the_garden.