Let’s face it: every publication is better with images. Whether it’s a presentation, a blog post, a book, or just a paper, images engage an audience instantly. The internet is flush with images from Islamic art, architecture, and society, but reliable sources (with credit information) are more difficult to track down. So we’ve done it for you! Here are some of the best sites for finding credited visual resources for Islamic, Middle Eastern and North African Studies. Feel free to suggest more in the comments and we’ll update the list! Note this list is specifically focused on images and visual resources, but not necessarily manuscripts (for a guide to online manuscript collections, look at Evyn Kropf’s list here).

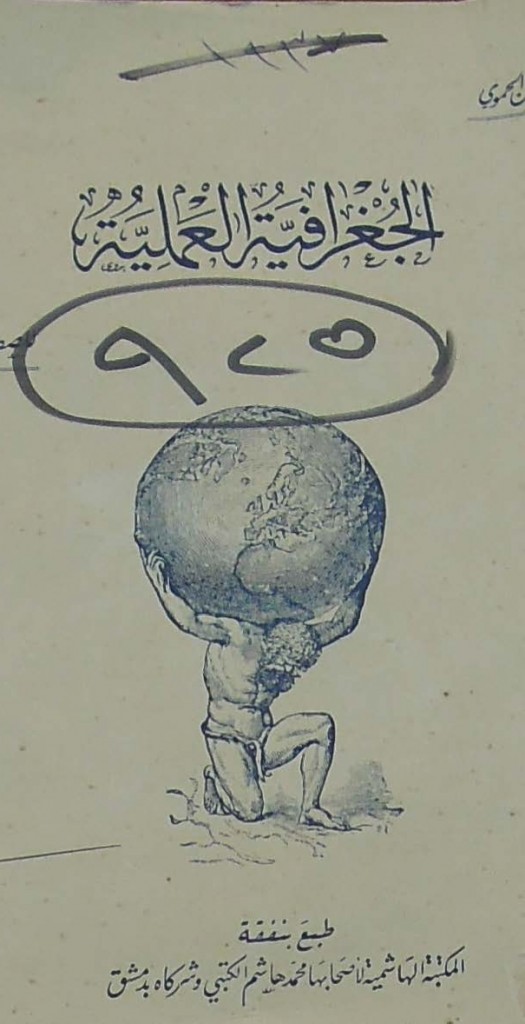

The Museum of Textbooks (Jordan)

The Museum of Textbooks or “Matḥaf al-Kitāb al-Madrasī” is a unique resource for historians interested in education, not only in Jordan, but also in Palestine, Egypt, Syria and Iraq. The museum is located on the grounds of the secondary school for boys in Salt, approximately twenty miles from Amman and houses textbooks used in Jordan, but written and published throughout the region. These textbooks mainly date from the 1920s through the present but also include a few Ottoman-era works, as well as documents relating to Jordanian education, particularly at the Secondary School for Boys.

History

The Textbook Museum originated in 1982, when its purpose and plans for establishment were outlined in the Government Gazette. It falls under the authority of the Ministry of Education. The Jordanian Ministry of Culture attributes the concept to Dr. Sa‘id al-Tel, Minister of Education in 1982. As the museum fell under the authority of the Ministry of Education, its original purpose was to collect textbooks used in the schools of Jordan and Palestine since 1921, as well as ministerial documents relating to the history of education in Jordan. These regulations were amended in 2006 and stipulated a number of significant changes to the museum’s central mission. Specifically, the museum planned to archive all educational material issued by the Ministry of Education and contribute to research on educational affairs by collecting and preserving educational documents regardless of their source, as long as they had been used in Jordan. Moreover, the museum planned to augment its public outreach through permanent exhibits on educational affairs, curriculum, and textbooks from Jordan and abroad, The museum opened in its current building in 2008.

Collection

The Museum contains a wealth of material relating to government-sponsored education in Jordan, as well as Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, and Iraq, particularly during the Mandate era. Its main interest, as is clear from its title, is in collecting schoolbooks used in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan from the early 1920s through the present day. Collectively, the museum and the school’s archive contain a variety of documents relating to education in Jordan. The documents pertaining to Boys’ School in Salt are also notable due to the school’s significance, as it was the only full high school in Jordan during the Mandate period.

As of 2012, there was no catalog. Textbooks are displayed on glass shelves, and arranged in cabinets organized by the decade they were published, although sometimes this can lead to confusion, as a later edition of a textbook may be located in the decade of its original publication. As Jordan did not produce its own textbooks for much of the Mandate period, its government relied on works from the rest of the Middle East, particularly Egypt and Syria, even for subjects such as civics. This means that researchers interested in education throughout the Arab world can find textbooks and pamphlets at the museum, particularly those dating from before the 1950s. After this period, most works were published in Jordan. The textbooks include all subjects taught in Jordan’s curriculum: history, Arabic language and grammar, English, religion, geography, elementary science, ethics, civics, and mathematics. The majority of the textbooks are written in Arabic, but there are many works in English that were used to teach the English language such as elementary readers and introductory histories.

The interior of the one-room museum is surrounded by framed documents in display cases. Researchers interested in education, and governance, in Jordan and Palestine should take care to look at these documents, which include diplomas from the Arab College of Jerusalem, exam certificates and results from Palestine and Jordan, and letters from the Department or Ministry of Education in Jordan to employees of the secondary school, generally focusing on nationalism and exhibitions of Arab unity. For example a 1923 letter written by the director of education describes the nationalist activities of teachers in the district of Ajlun.

The school possesses an archive documenting its own materials, although the classification status of these materials fluctuates depending on the date of the documents, as well as the schedule (and disposition) of the principal. These materials are housed in the school’s main building, and one should take care to meet with the principal first if one is interested in these materials. Documents on school attendance, teachers’ salaries, and student grades are contained in binders and on CDs, although I was not given access to the electronic materials. Recent documents are more difficult to access than those from the Mandate-era. Inside the school are photographs depicting its teachers and students from the beginning of the school through the present.

Since my visit, the Museum has created a Facebook page, and there is an informational video on YouTube (in Arabic).

The Research Experience

Few researchers, particularly foreign researchers, make use of this archive although that appears to be changing. This means that researchers may often find themselves alone with the employees of the museum. They speak little English, but are kind, friendly and very willing to help to the best of their ability. They are also quite interested in the research and life of researchers; be prepared to chat, eat, and drink while you work. There are tables and folding chairs set up, giving the researcher a surface on which to place the books, and to photograph them. The museum has no central heating, but is comfortably cool in the summer. There are restrooms, which generally work, including a western style toilet (at least in the ladies’ room), but bring your own toilet paper.

The school is very much a working school. This means that if you venture to seek documents from the school’s archive, you will be subject to the rhythms and interests of school life at a boys’ high school. When I was there, students were protesting the lack of central heating, which meant that every few minutes the principal and various teachers were dealing with the head of the student council throughout the morning while I was photographing documents.

Access

The Museum is open from approximately 8:00 until 14:00 or 15:00, depending on the availability of the museum’s employees. It is not open on Friday or Saturday.

It is useful to bring a letter of introduction from your university, and your passport, although these things are not necessary to use the Textbook Museum. I also found it useful to mention that I had heard of the Museum from a previous researcher. Feel free to mention my name as well.

It is more difficult to use documents from the school archive. I was initially allowed to photograph these documents, but a few days later I was refused. I was lucky in that the Minister of Education visited the school and Museum while I was there, and took the PR opportunity to give me permission to view the documents. My advice is to be polite, and persistent. However, most researchers will probably be more interested in the textbooks that are explicitly accessible to all.

Reproductions

The museum allows researchers to photograph all the materials within the museum without charge. In 2012, there were no facilities for photocopies, although the principal does have a photocopier that can be used for certain school documents.

Transportation and Food

The museum is approximately a twenty-minute drive and thirty to forty-five minute bus ride by bus from Amman.

The best way to get to the museum by public transport from Amman is to take a minibus in front of the University of Jordan. These small buses will have “al-Salt” written in Arabic on the side. There will also be a man yelling “al-Salt, al-Salt” from the door of the bus. It costs .5 JD, passed up to either the shouter or the driver during the ride. The ride takes approximately thirty minutes, depending on traffic and the number of stops to pick up passengers. The bus makes several stops along the way, but the al-Salt bus station is the final stop. The bus actually stops just above the station, coming from Amman.

To get to the museum, which can be seen up the hill, go towards the town but take a left, and continue winding up the hill. There are now signs pointing to the museum. If confused, ask for directions to the “al-madrasa al-thanawiya lil-banin.” Enter the main gate of the school and continue straight. The museum is on the right, down the hill. The boys and staff members are generally happy to give directions as well. To get back to Amman, retrace your steps but this time enter the bus station (a large parking lot of buses at the bottom of the hill) and take either one of the larger or smaller shared buses towards “al-Jami‘a” (the University of Jordan). As in Amman, there will be men shouting where each bus is traveling. Smaller buses often leave more quickly, and both are the same price. The bus towards “al-Jami‘a” stops in front of the university, by the Burger King.

There are grocery stores, and several restaurants in al-Salt, but little within a five minute walk of the school. As the museum’s hours are limited, it is best to pick up a snack on your way, which you are allowed (encouraged) to eat as you research. There is an open-air produce market in the main street of the town, which generally has fresher and cheaper produce than in Amman.

Miscellaneous

Salt also boasts a museum, in the Abu Jaber House, on the history of Salt that is well worth visiting. Its informational displays are well-researched, clear and new. This museum includes a prominent section on education, and has maps of Salt’s historic trail that includes directions to various architectural and cultural sites.

Contact information

Director: الأستاذ عمر العمايرة

Phone number: 0096253552118 (taken from here)

Resources and Links

-There is no catalogue available. Books are arranged in cabinets by decade.

For further information on the museum in English, see Professor Laurie Brand’s account of her research:

There is an informational video on the museum on youtube

The ministry of culture also has two segments of its website on the mission and regulations of the museum here and here

______________________________________

Hilary Falb Kalisman is a doctoral candidate in the History Department at the University of California, Berkeley. Her research focuses on the relationships between government-sponsored education and political culture in the late nineteenth through mid-twentieth century Middle East.

Citation information: Hilary Falb Kalisman, “The Museum of Textbooks (Jordan)”, HAZINE, 9 Oct 2014, https://hazine.info/museumoftextbooks/

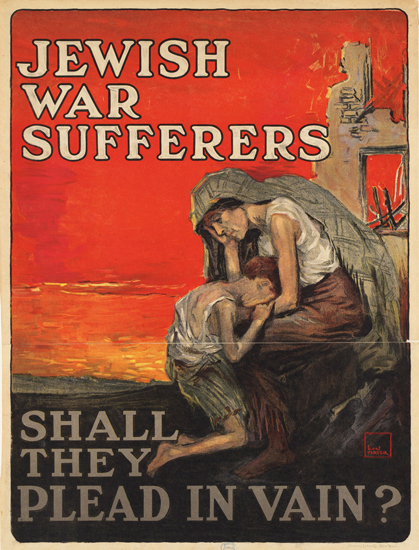

The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives (Jerusalem)

Written by Anat Mooreville

The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, known as the JDC or the Joint, is an international Jewish philanthropic organization started after the First World War to assist Jewish refugees in Eastern Europe and Palestine. With records of activities in over ninety countries dating from 1914 to the present, the JDC Archives are a significant resource to understand not only American Jewish relief efforts abroad, but also Jewish social, cultural, political, and economic conditions around the world. For the Middle East, the JDC Archives include records created primarily between 1940-1977 from Aden, Algeria, Cyprus, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Syria, Tunisia, and Turkey. Middle East specialists will find this archive particularly useful for conducting research on Jewish history in the Middle East and North Africa in the second half of the twentieth century. The archive has two locations—Jerusalem and New York City.

Collection

The JDC Archives are located in two centers, one at the JDC’s New York City headquarters and the other in Jerusalem in the Givat Sha’ul neighborhood. These centers are not equal in size and scope. The Jerusalem archive is the larger and more comprehensive of the two; in fact, all the records of the New York archive are available in Jerusalem in microfilm format.

The archive in Jerusalem houses the records of JDC field offices throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia, along with the records of JDC operations in Israel. The bulk of the Middle Eastern and North African records of the JDC are part of the Geneva Files (1945-1977), which were subsequently shipped to the JDC Archives in Jerusalem after the Geneva Office—opened in 1957 as the European headquarters of the organization—was closed in 1977.

Although this review focuses on the Jerusalem archives, I will briefly outline what is available in the New York collection. The New York archive houses American headquarters communications with governments, national and international agencies, and JDC field offices. The bulk of the archival record concerns relief, rescue and support activities in Europe between 1914 and 1945. Later materials concern JDC activities in the Displaced Persons (DP) camps of Germany, Austria, and Italy, and JDC activities in Eastern Europe during the Communist period. For the Middle East historian, the New York archives detail the medical, educational, vocational and relief activities in Palestine starting in 1914 through the Second World War. These include institutions established to help the disabled and orphans. A detailed list of these files are available online through the finding aids (search by country). They also contain information on refugee and aid activities in North Africa during the Second World War.

The JDC Archives includes over three miles of text documents, 100,000 photographs, a research library of more than 6,000 books, 1,100 audio recordings including oral histories, and a collection of 2,500 videos, covering 90 countries throughout the twentieth century. Many of the collections are arranged chronologically, others by subject or office of origin (e.g., Geneva, Rome, Istanbul). At the same time, the JDC is an active Jewish humanitarian assistance organization. All JDC historical records older than thirty-five years are open to the public with the exclusion of materials containing information that the JDC believes would adversely affect its ongoing work.

For the period following the founding of the State of Israel, the JDC Archives in Jerusalem contain files related to Malben (נֶחֱשָׁלִים בְּעוֹלִים לְטִפּוּל מוֹסְדוֹת “Institutions for the Care of Disabled Immigrants”), the social service organization created jointly by the JDC, the Jewish Agency, and the Israeli government in 1949. Malben provided institutional care and social services; established hospitals, clinics and old-age homes; trained nurses and rehabilitation workers; and fostered the development of private and public organizations in Israel for the care of the disabled. Files also document missions and programs to help settle Jews from North Africa and the Middle East in Israel. For example, the JDC organized Operation Magic Carpet, which evacuated about 48,000 Jews from Yemen to the newly established State of Israel and Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, which brought approximately 120,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel.

Records related to the Middle East and North Africa document the JDC’s medical, educational, and vocational support in these regions from the late 1940s through the 1970s. These social efforts were wide-ranging and expansive. In North Africa, JDC initiated public health programs with OSE (Œuvre de secours aux enfants) to combat diseases such as tuberculosis and trachoma. The JDC frequently offered assistance to local Jewish educational organizations such as Ozar Hatorah and Alliance Israelite Universelle. Numerous country reports document local demographic, economic, political, and social conditions from the perspective of the JDC’s staff.

The photography collection of the Middle East and North Africa is quite large and can be fully searched by title, description, date, subject, location, photographer, and other fields on the JDC Archives’ online catalog. To see the range of photographs available, we recommend the galleries on Algeria in the 1960s, Tunisia in 1950s, and early Palestine.

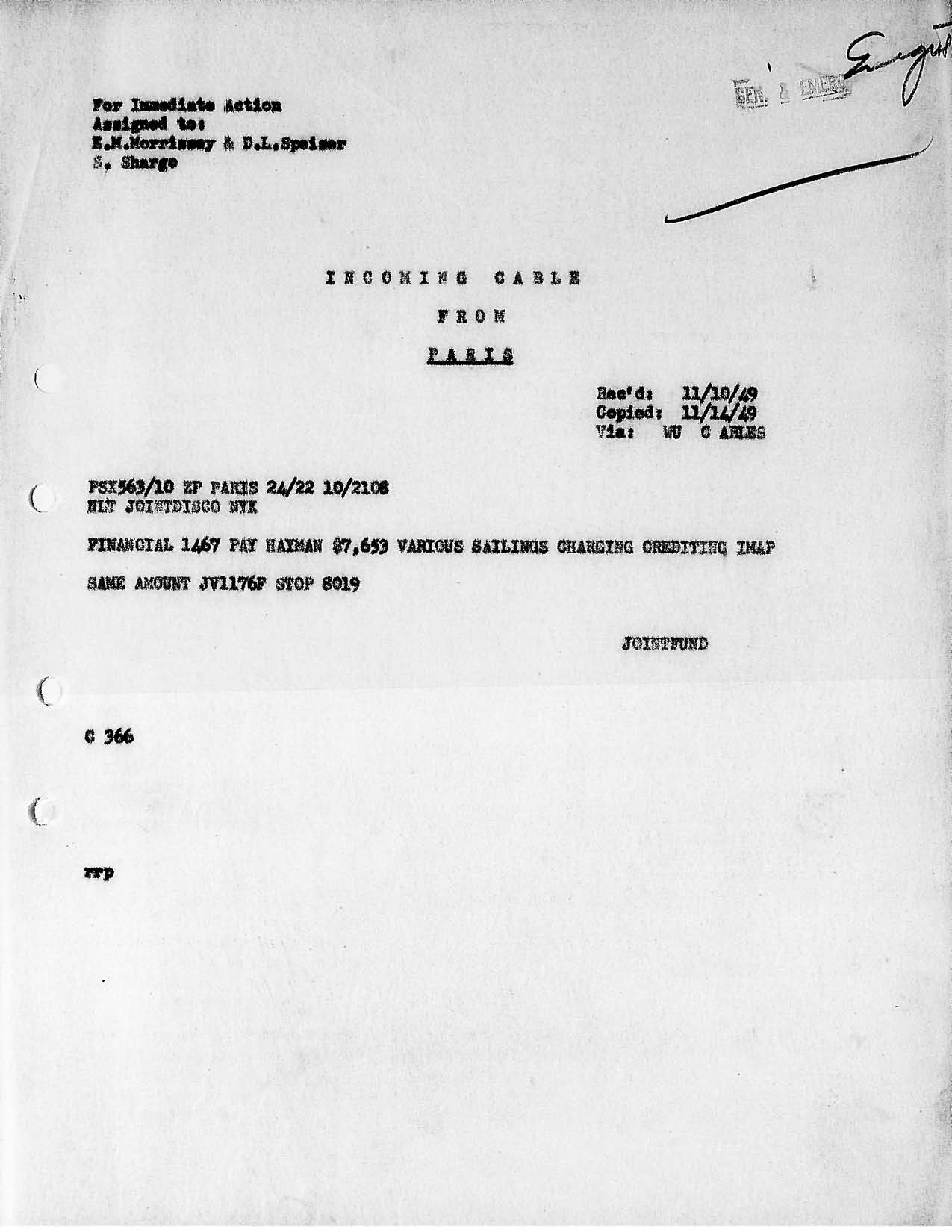

A sampling of the range of materials available in the JDC archives include correspondence, committee and board meeting minutes, field reports from worldwide staff, financial statements; memoranda, lists of aid recipients and supplementary allocations, program descriptions, passenger lists, cables, supply lists, restitution laws and statutes, summaries of statistical reports, personnel files, legal files, case files, conference proceedings, lists of names, audits, brochures, press releases, pamphlets, and news clippings.

Research Experience

The JDC Archives is in the process of digitizing its collections. While the photo database is fully available online, other text resources are only partially available. The online catalog is a good place to begin your search, and some documents can be accessed through the website directly, but keep in mind it is in no way exhaustive, especially for Middle Eastern material. There is a very brief finding aid for the Geneva Office of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee 1945-1954 records, but it does not detail the Middle East/North Africa collection. The records of the Istanbul office (1943-47) or the Geneva office (1955-1978) are not available online. You can learn more about how to search the online database by viewing the archive’s video tutorials or reading its guide. The JDC Archives staff has access to a more comprehensive online catalog that is password protected.

To access the full catalog of the JDC Archives in Jerusalem, one must first e-mail Shachar Beer to make an appointment to visit. Only one or two researchers are allowed at a time, as the archive is located in one of the working offices of the JDC. On your first visit, Mr. Beer will give you a stack of binders that contain the full catalog. Unfortunately, they are not arranged by country, and it is advisable to spend the first day examining all the binders for relevant material and noting the title and file code that you wish to order during subsequent visits. Researchers should note that since March 2013 the archive has been in the midst of reclassifying its files and consequently the code which appears on the physical file may differ from its new classification. You therefore may not be able to order material on your first day. Material can only be ordered once a day and is limited to five or six boxes (more if the material is microfilmed). These should be ordered in the morning or emailed to Mr. Beer before your visit. The time of retrieval of material is not routine, but it usually arrives from the warehouse before 11:00. Once requested, it usually takes about thirty minutes to an hour for material to be prepared for the researcher. One should also coordinate with Mr. Beer the time of arrival to the archives in the morning, which can be as early as 9:00 or as late as 11:00, depending on his schedule.

Since the JDC Archive in Jerusalem only accommodates one or two researchers per day, I would recommend allotting at least a few days for research to get the most of out of your scheduled visits. It takes some time to become familiar with the full holdings because they are not online, and one can only see a limited number of files per day.

There is one microfilm machine, as well as a spare office and a conference room in which Mr. Beer directs researchers to work with original files. The catalog does not indicate whether the file exists in microfilm or only as an original. Since the archives are in the office of a working NGO, it is mainly full of JDC staff, the archivist, and perhaps one other researcher.

Access

In order to visit the archives, one must fill out an application located online. Once permission is received (usually less than a week), you need to email Mr. Beer to schedule an appointment.

Although the stated hours of the Jerusalem Archive are Sunday-Thursday 9:00-15:00, the actual hours depend on the appointment times scheduled with Mr. Beer. Generally, researchers may work at the archive until the JDC office closes around 16:00.

Reproductions

Reproduction services (photocopy and microfilm printing) are not available. You are allowed to use a digital camera to photograph files and microfilms. There is a one shekel fee for each photograph. Researchers tally their own photographs and report them to Mr. Beer at the end of each session. In some cases, Mr. Beer will waive the fee for photographs of microfilm material.

Transportation and Food

The archive is located in the industrial park neighborhood of Givat Sha’ul in West Jerusalem. It is not easily accessible from downtown Jerusalem. Buses 33 and 67 stop outside the archive, and it is about a ten minute walk from the Kiryat Moshe light rail station.

There are many chain restaurants and cafes in the archive building and nearby that cater to the business crowd. There is free coffee and tea in the archive itself. You can also bring your own lunch and eat it in the archive.

Miscellaneous:

The JDC Archives offers a fellowship to conduct research in either the New York or Jerusalem Archives. Check the website for details and application.

Future Plans and Rumors

The archive is in the midst of digitizing its collection, so the state of the online catalog and available digitized files is constantly changing.

Contact information

JDC Archives

Beit Hadefus Street 11, Lobby 2, Floor 3

02-653-6403

General information: Archives@jdc.org.il

Archivist: Shachar Beer <ShacharB@jdc.org.il>

Resources and Links

The online catalog is sophisticated and contains 900,000 digitized pages. However, it is not complete, especially in regards to Middle Eastern and North African materials.

The archives website is quite expansive and details the history of the JDC, the archives, and contains various finding aids and resources on how to search the archive.

**Information about the history and holdings of the collection comes from the JDC Archives website.

Anat Mooreville is a doctoral candidate in the UCLA History Department where she studies twentieth-century Jewish and Middle Eastern medical history.

Cite this: Anat Mooreville, “The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives (Jerusalem), HAZINE, 2 Feb 2014, https://hazine.info/2014/02/02/jdc/

Gazi Husrev Begova Library

Written by Nir Shafir

Gazi Husrev-Begova Biblioteka (hereafter GHB) is the largest collection of Islamic manuscripts and documents in the Balkans. Located on the premises of the mosque complex of the same name in Sarajevo, the well-catalogued collection and brand new library is one of the premier locations for the study of the Ottoman Empire in general and the Balkans in particular. At the beginning of 2014, the library will officially open a state-of-the-art building to researchers and the general public.

History

Like many manuscript libraries in the Islamic world, the collections of Gazi Husrev Beg Library coalesced as it aggregated the manuscripts and papers of various medresas, Sufi lodges, and private libraries over the years. The complex that houses the library was constructed by that great sixteenth-century benefactor of Sarajevo—the eponymous Gazi Husrev Beg. Starting with a medresa, dzami, hanikah, and a market, it grew to include various tombs and a clock tower displaying lunar time. In 1697, however, Eugene of Savoy razed Sarajevo, supposedly destroying many of the books and ledgers in the process. While the medresa was endowed with a small group of books, a separate library building was only built for the medresa in 1863. (Two other library buildings in Sarajevo predate this library though they are no longer extant.) In the twentieth century, the library began to incorporate the collections of other institutions and private individuals. The first volume of the catalog was published in 1963 and followed by subsequent volumes of equal detail over the years. During the 1991-1994 war, the manuscripts and defters were hidden away in private homes and bank vaults and so they were spared the fate of the Oriental Institute collections, which were completely destroyed in a fire started by the shelling of Serbian artillery. In January 2014, a new, ultra-modern library building, built with the generous donations of the Qatari royal family, will be opened. The al-Furqan Foundation has also supported the continued publication of the high quality catalog. The library has recently completely digitized its collections, which continue to grow today through the donations and bequests of individuals.

Collection

The library’s main collections consist of Islamic manuscripts, printed books, documents such as court records, and photographs. The manuscript collection contains around 10,500 volumes in Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and Bosnian (in Arabic script). Of these languages, the first two tend to predominate. Given that many of the books in Sarajevo apparently did not survive its razing in 1697, the manuscript collection is heavily weighted toward topics, authors, and copies from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The collection seems to include a much higher than average concentration of moralistic, dogmatic, and sermon-like texts than other manuscript collections and so researchers can find a wide array of texts condemning practices like tomb visitation or tobacco smoking. Similarly, there is a large number of manuscripts copied by medresa students, as evinced by the surfeit of treatises on education. While such treatises were popular throughout the Ottoman Empire, the local origins of many of these copies provide researchers a glimpse of the local intellectual

culture. Researchers can gain further insight into this local culture by reading the small but significant number of treatises written in Bosnian, the vernacular of the region. These treatises, too, are often prayer books or moralistic exhortations. At the same time, the collection points to the many Bosnian scholars who traveled to Syria, the Hijaz and Istanbul in the early modern period. There are, of course, a good number of older and more “precious” books and the library’s promotional brochure highlights some of these.

In addition to its manuscripts, the library contains one of the largest collections of early print in the Balkans. The library’s holdings comprise over 25,000 printed treatises in Arabic, Turkish and Bosnian (in Arabic scripts). In addition, it also has a collection of around 35,000 books in Bosnian and other European languages in Latin script.

The library also houses various documents from the Ottoman period. Of these, the most comprehensive are the court records (sijillat) of Sarajevo and the more limited collections for the neighboring cities of Mostar, Tuzla, and Fojnica. For Sarajevo, these records exist primarily for the eighteenth century, starting from 1707 and ending in 1852. Records from before that period are presumed to have been destroyed in the razing of the city in 1697. Three volumes of sixteenth-century court records do exist, however, for the years 1551-1552, 1556-1558, and 1565-1566. For Mostar there are two registers covering 1766-1769, for Fojnica a single register covers the years 1763-1769, and a partial register from Tuzla exists from the first half of the seventeenth century. In addition to this, there are 1,600 endowment charters (vakifnama), 500 as individual documents and 1,100 within the court record defters. Paired with these, there are around 5,000 documents produced by the Ottoman bureaucracy. Library patrons consult these documents as digital copies.

Finally, the library houses a special collection documenting the Muslim community of Bosnia. The community’s archives cover the period of 1882-1993 and complement the large collection of 5000 photographs, postcards, and posters held in the library. The library also holds complete collections of many nineteenth-century Muslim newspapers from Sarajevo.

Research Experience

The manuscript collection of Gazi Husrev-Begova Library, along with those of the other manuscript libraries in Sarajevo, bears the distinction of being extremely well-cataloged. The eighteen-volume printed catalog, written by numerous individuals, is essentially divided into two: the first nine volumes or so describe collections present in the library until around 1970 and the second half details acquisitions after that date. In both halves, works are categorized topically. The catalogers made a smart choice to maintain the conceptual unity of each codex: all the treatises in a mecmua, which comprise the vast majority of volumes, are listed after the first entry. Codices are placed under specific topics according to their first work, which means that the topical organization of the catalog is slightly loose. Researchers should browse through indices of every volume of the catalog if they are looking for particular authors or titles. The catalogers were particularly attentive to the details of manuscript production; they mention copyist names, owners, locations, physical characteristics, as well as any unique aspects or contents of a manuscript in each entry. Excellent indices exist for author name (in Arabic and Latin scripts), title, copyist, owner(s), and location. Mistakes, while present, are rare. The catalog is written in Bosnian, but there should also be an English translation available. The catalog often quotes material directly in Arabic, so researchers can simply read the quoted text. There had been an electronic catalog available, although the library removed it recently from its website due to poor performance. In its place, the library is actively developing a new electronic catalog that it hopes to roll out in the coming months.

The printed works in the library have traditionally received less attention than the manuscripts although this is quickly changing. The library has recently finished cataloging them and once the new electronic catalog is online, researchers should be able to access the catalog of printed works. Some of these printed treatises were even part of the collections of the Ottoman-era libraries from the eighteenth century, though the new catalog might not list the original collection name for each entry, and therefore researchers must go through the volumes individually to find this information.

It is very pleasant to conduct research at Gazi Husrev-Begova Library, especially since the opening of the new building. The building has a large general reading room with excellent desks and ample windows overlooking the medresa complex. The desks have good overhead lamps. The reading room should eventually have a large collection of reference material but is empty for now.

To request a manuscript researchers should first browse through the printed eighteen-volume catalog of the library. A Bosnian- and English-language copy of the catalog is kept behind the reception desk and the staff will let you browse a couple of volumes at a time. Once the library introduces the new computer catalog, researchers should also be able to use the single computer terminal at the reception desk to find relevant manuscripts. You must stand to use this computer since it was not set up for consultations longer than a few minutes. Once researchers identify a manuscript they wish to consult, they can fill out a form and request up to twenty manuscripts at a time. After twenty minutes to an hour, the digitized copies of the manuscripts are transferred to a computer terminal in a second reading room behind the reception desk for consultation. If library patrons wish to buy copies of the digitized manuscripts, they must fill out a further form that is then sent to the director for approval. The staff might let you simply delete unwanted files on your terminal and burn the remaining images onto a CD or they might prepare the specific pages you request. Researchers can request to see the physical copy of the manuscript only after receiving permission directly from the director of the library.

The new GHB library was largely designed with digital research in mind. The quality of the digitized manuscripts is generally high, though there are the occasional low-resolution images. Generally speaking, the binding of a manuscript is photographed though this might be limited to the cover itself. Conveniently, an information slip from the catalog listing its title and author precedes the digital copy of each work, even separate treatises in a mecmua. The only inconvenience is that researchers cannot access the digitized manuscripts directly from the computer catalog.

The staff of the library are extremely helpful and professional. The working language of the library is Bosnian, though employees at the reception desk should be able to speak English, Turkish, or Arabic.

Researchers should note that as the library settles into the new building, new protocols and procedures will be instituted, so some of this information might change in the near future. For instance, there is a large reference library of books in Bosnian, English, Arabic, Turkish, and more available to researchers, but it is not currently on the shelves. The library, however, is constantly striving to improve researcher experience and will make changes as needed.

Access

The library is open Monday to Friday, from 8:00 to 15:00. It is closed on the weekends along with secular and religious holidays. Researchers are advised to talk to the receptionist to keep abreast of religious holidays in Bosnia, which can be a bit different from those in other Muslim countries.

The library, like all research institutions in Sarajevo, is very welcoming to researchers. After a short registration process, in which researchers might need to provide a formal ID, researchers can access the collection.

The main entrance of the library might not be wheelchair accessible, but researchers in wheelchairs should be able to enter from the employee entrance on Mula Mustafe Bašeskije Street.

Reproductions

Digital reproductions are provided in the form of a CD. The price is a somewhat costly at €1 per exposure and the CD will be ready for pick-up three days after the initial request. The delay is a bit odd, since all the material is already digitized, but researchers in a hurry might be able to expedite the process with the help of an accommodating staff member. In the future, the library hopes to introduce a system that will allow researchers to request digital reproductions remotely. Researchers are not allowed to take their own photographs as they are not allowed to see the original manuscript or defter.

Transportation and Food

The library is located in the center of the old city of Sarajevo and is easily accessible by the tram. Researchers can alight at either the cathedral or the last stop— Baščaršija. The very modern looking library building is located in between the two stops, next to the Gazi Husrev Begova Dzamija complex and the Old Synagogue/Jewish Museum. If researchers stay at hotels or hostels near the historic center, the library is easily reached by foot.

There is no shortage of eating options near the library as it is in the center of the historic city. Next door there are a variety of cafes and burek sellers as well as quite a few more touristy restaurants. There is also a small café in the library itself that serves Turkish tea, Bosnian coffee, and espresso.

Miscellaneous

The library also houses a museum in the basement that exhibits certain rare manuscripts and various material artifacts related to writing, reading, and daily life in Sarajevo. Various marble inscriptions from Sarajevo dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are also displayed in the basement for the time being. There are also conference facilities in the library itself.

Since 1972, the library has also published a journal titled Anali Gazi Husrev-begove biblioteke, of which free copies are available online. The informative journal highlights the historical research of scholars from the area. Although the journal is written in Bosnian, researchers can render the text searchable and then copy the text into Google Translate for a relatively functional translation.

Future Plans and Rumors

The library will officially open to researchers on January 15, 2014. Some of the protocol listed above will inevitably change as the library streamlines and refines its procedures. As stated earlier, the library hopes to reintroduce a new computer catalog on its website and even provide researchers the chance to request copies remotely.

Contact information

Gaza Husrefbeg no. 46 Sarajevo 71000 Bosnia and Herzegovina

Phone: +387 33238152, +387 33 264 960

Fax: +387 33205525

Resources and Links

Gazi Husrev Begova Biblioteka main site

Annals of Gazi Husrev Begova Library

23 December 2013

Nir Shafir is a doctoral candidate at UCLA researching the intellectual history of the Ottoman Empire during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Cite this: Nir Shafir, “Gazi Husrev Begova Library,” HAZINE, 23 Dec 2013, https://hazine.info/2013/12/23/ghb_library/

Central Zionist Archive

Written by Liora R. Halperin

The Central Zionist Archive (hereafter CZA) in Jerusalem is the main archival resource for scholars researching the history of the Zionist movement, both within Palestine/Israel and internationally, and the history of the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine) during the British Mandate and late Ottoman periods. Any scholar researching a topic that relates, either directly or indirectly, to the Jewish community in pre-state Palestine or the international institutions of the Zionist movement (e.g. the World Zionist Organization, the United Israel Appeal, or the Jewish Agency) will find the CZA to be an important archive.

History

The Central Zionist Archive was founded in Berlin in 1919 as the archive of the Zionist Movement; its goal was to collect the documentation of the branches of the Zionist movement located around the world, as well as the personal archives of key Zionist leaders. The first director of the archive, Georg Herlitz, began ordering the archive according to the organizational structure of the various offices that produced the documents in the collection. In the wake of the Nazi rise to power in 1933, the archive was moved to Israel and opened to the public in 1934. At this point, the collection’s focus expanded well beyond the history and bureaucratic activities of the global Zionist movement to include also the history of the Yishuv and Jewish settlement in Palestine. Alex Bein, the long-serving director of the archive, worked to realize the expansion of the collection as well as the transfer of Theodor Herzl’s archive to Palestine in 1937. Bein also gathered the personal archives of several other early Zionist figures. After being located for decades in the basement of the Zionist institutional offices on King George Street, the archive was moved into its current location in 1987.

Collection

Next to the Israel State Archives, the Central Zionist Archive is the largest archive in Israel. The Central Zionist Archive has, according to one estimate, about 80 million documents—a quantity which one writer described in 2007 as “ten kilometers of Zionism” (Anat Banin, “The Treasure Vault of the Jewish People” The Jewish Magazine, Hanukkah 2007). The CZA contains the archives of, among other bodies, the committees, subcommittees, and offices of the World Zionist Organization, as well as the Jewish Agency, the Jewish National Fund, the United Israel Appeal (Keren Ha-Yesod), and the Jewish National Council (Va‘ad ha-Le’umi). It also holds the records of other Zionist organizations and institutions in countries around the world and in Palestine/Israel, the records of Zionist Congresses, and over 1500 personal archives as well as extensive collections of periodicals, images, and maps. Most of these documents were produced in bureaucratic offices, mainly in the twentieth century, with a smaller number of documents from the late nineteenth century and a growing collection oftwenty-first-century collections from currently active Zionist organizations around the world. Approximately one-third of these documents are from the period of the Holocaust, making the CZA an important source for materials pertaining to Zionist activity during the Second World War. It also has a large collection of newspapers, maps, and half a million photographs and negatives. The CZA also has a unit for family research, and charges a fee of 100 shekels for individuals and 150 for institutions to look into immigration records, primarily for those who entered the country between 1919 and 1974. It also possesses a large book collection.

The contents of the CZA’s collections and sub-collections are listed on the archive’s website, which was updated relatively recently and is user-friendly. Researchers are advised to use the online lists and come on the first day of research with an initial list of materials they wish to order.

It should be noted that the documents held in the Central Zionist archive, with a few exceptions, were those either created or received by the Zionist movement, or, more specifically, associates of the Zionist Organization, as opposed to affiliates of the Labor Zionist or Revisionist movements. A wide range of organizations associated with the Zionist labor movement including MAPAI, Ha-Shomer Ha-Tza‘ir, the Kibbutz HaMe’uhad, the Histadrut, as well as the archives of the Revisionist Movement and of local municipalities, are held in other organizational or municipal archives located around Israel. Moreover, while the Central Zionist Archive is a central archive for the history of pre-state Zionism and the proto-state institutions of the Yishuv, the archives of the British mandatory government in Palestine are not held at the Central Zionist Archive, but rather at the Israel State Archives, where they were transferred after the creation of the state. A basic understanding of the structure and political diversity of the Zionist movement is essential to predict whether a given document or collection is likely to be held at the CZA or a separate archive elsewhere in Israel.

While the CZA holds materials from the Jewish community of Palestine up to 1948, it also contains and continues to collect the documents of certain international Zionist organizations outside the direct purview of the Israeli state. Given the worldwide nature of the Zionist movement, the archive contains materials from all major sites of Zionist movement activity including Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and South America. It contains materials from Palestine and from other Middle Eastern locations where the Zionist movement was active. Given the global reach and extent of these materials, the archive has important information on other topics, for example, global Jewish communities, resistance to Zionism, major events in Jewish history, the Arab population of Palestine, etc. However, visitors should plan their research mindful of the explicitly political and ideological logic—chronicling the history of the Zionist movement—by which the collection was assembled. The bulk of the collection is in Hebrew, but Zionist records from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century are more likely to be in German, and the records and correspondence of Zionist organizations around the world will likely be in the state languages of their respective countries.

Research Experience

The collections are organized, by and large, with reference to a document’s institutional place of production. In other words, the structure of the collections follows the structure of the institutions from which they came. Each top-level archival designation refers to a different institution. Some of the largest are the Va’ad Ha-Le’umi (Jewish National Council, archive code J), the Jewish Agency (archive code S), the Jewish National Fund (archive code KKL), Keren Ha-Yesod (United Israel Appeal, archive code KH), Zionist Organization Offices in various cities (archive code Z), and the Zionist Commission (archive code L). The number following the initial letter usually refers to a particular office or committee within the organization (e.g. J2 or S25). The number following the slash is the folder number. Personal archives have designations starting with the letter A. Although it is possible to find files by keyword, it is helpful to pay attention to the top-level letter and number for any given source in order to understand accurately its bureaucratic origin.

There are two basic ways to access catalogs. The computerized catalog is the main way to search for files, and one can search by keyword, as well as by year and other parameters. The operation of the computerized catalog is not immediately intuitive, and researchers should plan to ask for help from the reading room staff.

The second way to search the collections are through the bound volumes for each archival unit, which are organized by letter and are located to the left of the main desk in the reading room. Some of these volumes are missing, but if the one you need is on the shelf, the low-tech browsing method can be a useful way to understand the overall organization of each archival unit. Researchers normally request material through the computer system. In the event that the computer system is inoperable, researchers may continue to make requests using the paper slips. In my experience, computer outages are not uncommon, but this issue may have been resolved.

Thanks to support from the Judaica Division of the Harvard University library, the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC, and the Claims Convention, the organization that distributes and allocates the funds of German Holocaust reparation payments to Israel, the CZA is digitizing its collections and researchers should expect that a good proportion of their documents will be viewed not on paper but on the computer terminals located in the reading room. Digitized documents are not always high quality, and, except for maps and other full-color documents, scans are in black and white. It is therefore occasionally difficult to read documents. Moreover, the functions for zooming and moving between pages are sometimes frustrating and the overall experience of dealing with scanned documents may be more difficult and less efficient than handling paper documents. In cases where the digital copies of documents are illegible, one can request paper files, but there is not an organized or streamlined procedure for such requests.

There are five pull times over the course of the day: 9:00, 10:00, 11:30, 13:00, 14:00. Five items (a book, a folder, etc.) may be requested at each of these times, for a maximum of twenty-five items over the course of a day. This means that researchers who intend to look at a large number of files will need several days before all their files can be brought. However, once a set of files is requested, it can be stored on a hold shelf indefinitely as long as you are still working with it. Files that are scanned can be accessed at any time, so it makes sense to start the day focusing on what files need to be ordered, and then work with scanned files while waiting for the paper files to arrive.

The reading room staff are helpful. It is important for researchers to enter with the mindset that they need to continue asking questions if they find the initial responses insufficient. The reading room staff speaks some English but researchers who do not know Hebrew often find this to be a real impediment to their research. It is also not a bad idea to ask other archive users for help if the archive staff is away from the desk. The reading room staff, though they can answer questions about the procedures of ordering files or making copies, are not the ones to answer research questions or questions about the organization of the archive. Instead, researchers should turn to Batia Leshem, Head of Institutional Archives, or Rochelle Rubenstein, Deputy Director of Archival Matters, for those sorts of conversations. Their offices, as well as the offices of other archivists, are located one level below the reading room. Ask at the security desk in the lobby for specific directions to their offices.

The reading room is sufficiently comfortable. It tends to have enough room for the number of researchers who are normally working there without feeling either empty or overcrowded. It is air-conditioned. Researchers are asked to deposit their belongings in a locker outside and not bring in food or water. There is not an extremely rigorous search process in this regard but researchers should be prepared to abide by these regulations.

There are a wide range of reference volumes in the reading room itself, including dictionaries between Hebrew and a variety of other languages, a range of different historical and biographical encyclopedias, and a range of books about the history of the Zionist movement.

Access

The archive is open between 8:00 and 15:30, Sunday through Thursday. Users should be aware that the archive is closed for all major Jewish and Israeli national holidays, including often the whole day or half day of the eve of a holiday. Given the seasonal arrangement of holidays, this means that researchers planning travel in September-October and April-June in particular should consult a calendar and make sure that they are not planning research during a period of multiple holiday closures. In addition, the archive closes for a break in mid-August (call ahead before you come since closure information is not always posted on the website).

Access to the archive is granted after the submission of a short application. Researchers should make an application appointment and come to the archive with their Israeli identification number or foreign passport number.. Researchers have gained access without a formal letter of introduction, but it is not a bad idea to have one, especially for doctoral students. Once one is in the system, one does not have to fill out subsequent paperwork for future visits, even if one is working on an entirely different project, but it is helpful to consult with the archive staff to orient oneself around each new topic.

The archive is wheelchair accessible.

Reproductions

Researchers are asked to pay (as of 2012) 40 agorot per page for photographs taken on a personal digital camera. This is charged through self-reporting. It is useful to be able to customize one’s own images, zoom or crop as desired. Also, this is the cheapest form of reproduction available.

If one wishes to have photocopies made of paper files, they must be marked on a special ordering sheet and cost 1 shekel per page. They are normally ready within a week.

Documents that have been scanned cost 1.50 shekel per page if printed and 2 shekalim per page if emailed and they must be ordered and take some time to arrive (this is another reason why it is often a boon to chance upon files that have not yet been scanned that you can photograph with your own camera).

Transportation and Food

The CZA is located directly across from the Jerusalem Central Bus Station and next door to the Binyane Ha-Umah International Convention Center. The CZA is extremely well serviced by public transit. The light rail makes a stop outside the Central Bus Station and any bus, whether in the city or inter-city, that serves the Central Bus Station will do (from the bus station cross Jaffa Road and Zalman Shazar Ave. Follow Josef Herlitz Rd off of Zalmar Shazar Ave to the right of the Convention Center to get there.) In addition, it is useful to know that it is only about a twenty-minute walk between the Central Zionist Archive and the National Library at Hebrew University’s Giv’at Ram campus. This proximity between institutions is useful to maximize one’s working hours, as the CZA closes at 15:30, while the National Library remains open until 19:45.

There are a couple food options near the Central Zionist Archive. A small food cart on Zalman Shazar Ave. near the bus stops sells snacks and basic prepared sandwiches of poor quality. The other option is crossing over to the Central Bus Station, which has a food court with decent fast-food style options. The bus station is also a reasonably pleasant place to get coffee or a pastry and it has free wi-fi and various shops. If you want to make the most of the research hours between 8:00 and 15:30, however, the best idea is to pack a lunch.

Miscellaneous:

The archive occasionally hosts lectures and symposia related to topics in the history of the Zionist movement. Sometimes it also organizes small exhibits in its lobby space.

Future Plans and Rumors

The archive plans to continue digitizing files.

Contact information

Website: www.zionistarchives.org.il

Address: 4 Zalman Shazar Avenue, Jerusalem

Director: Yigal Sitry

Phone number: 972-2-620-4800

Fax: 972-2-620-4837

Main contact email: cza@wzo.org.il

Other emails and phone numbers:

| Academic Director | Dr. Motti Friedman | 02-620-4803 | motif@jazo.org.il |

| Administrative Director | Gili Simha | 02-6204800 | gilis@wzo.org.il |

| Deputy director for archival matters | Rochelle Rubinstein | 02-6204816 | rocheller@wzo.org.il |

Heads of Departments:

| Institutional archives | Batia Leshem | 02-6204818 | batial@wzo.org.il |

| Private archives | Simone Schliachter | 02-6204817 | simones@wzo.org.il |

| Photograph Collections | Anat Banin | 02-6204825 | anatb@wzo.org.il |

| Graphic Collections and Maps | Nechama Kanner | 02-6204810 | nechamaka@wzo.org.il |

Resources and Links:

3 December 2013

Liora R. Halperin is assistant professor of History and Jewish Studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Her research focuses on Jewish cultural history, Jewish-Palestinian relations in Palestine and Israel, language ideology and policy, and the politics surrounding nation formation in Palestine in the years leading up to the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. Her first book, tentatively titled Babel in Zion: Hebrew and the Politics of Language in Palestine, will be published by Yale University Press in 2014.

Cite this: Liora R. Halperin, “Central Zionist Archive,” HAZINE, https://hazine.info/2013/12/03/central-zionist-archive/, 3 Dec 2013