By Noman Baig

To propose and teach a practice-based course in a highly academic setting is a formidable task. Practitioners usually face resistance from theoretically minded academics who perceive hands-on training as a lowbrow vocation. Last year in 2020, after practicing Islamic calligraphy for a year under a disciple of Kashif Khan (b. 1978), I decided to teach an undergraduate course on the subject at the newly established liberal arts college Habib University in Karachi, Pakistan. My home department, Social Development & Policy, rejected my proposal on the pretext that traditional art has no place in developmental studies; that it does not address pressing challenges in the way the discipline of economics does.

After initial resistance, the newly launched Comparative Humanities program[1] agreed to host the course as a creative practice requirement. Designed as an experimental course, Divine Proportions: Introduction to Islamic Calligraphy fused drawing and thinking into a singular aesthetic experience of the Islamic arts. The challenge was teaching aesthetic theory in tandem with drawing. The gap was overcome when I took the lead in teaching the historical-mythical aspects of the art. The calligrapher Ustad Kashif Khan took the responsibility of teaching calligraphy. In the first half, students discussed the readings and delivered presentations. In the second half, Ustad Kashif Khan taught them the art of drawing letters.

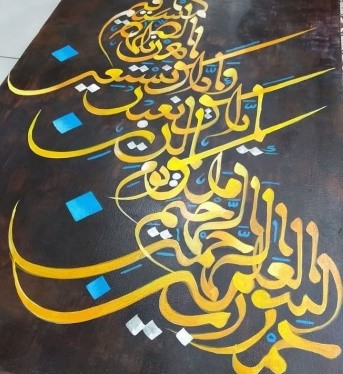

The syllabus had a vision of introducing students to Islamic calligraphy, beginning from when scribes used papyrus and parchment. It covered medieval calligraphers, exploring the mystical dimensions of letters, and finally, modern calligraphers. The course objective and learning outcomes focused on exploring fundamental concepts and themes in Islamic art and aesthetic theory, introducing students to the classical and contemporary forms of Islamic calligraphy, practicing writing with traditional methods, cultivating aesthetic sensibility in students and explaining the effects of writing on Muslim cultures globally.

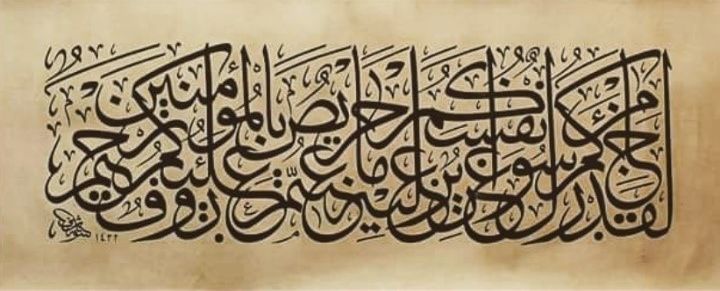

We assessed students on the class presentations, practice book, and two assignments: calligraphic letters and Surah Al-Fatiha. Given the logistical challenges and limited time (15 weeks), Kashif Khan suggested teaching the modern Kufic style. “You don’t need a reed qalam for Kufic. It is drawn on graph paper with the right ratio and then transferred onto a drawing paper sheet. We can easily have an output in fifteen weeks,” said Khan. After agreeing on the script, we started the first session on the concept of beauty in Islam. Sheila Blair’s magnum opus Islamic Calligraphy proved helpful in historicizing the art in its various iterations. The students’ reactions were phenomenal. The class had thirty students from social sciences backgrounds and the majority showed extraordinary enthusiasm towards learning calligraphy. We were then able to display the students’ final projects online.

In Lines: A Brief History, anthropologist Tim Ingold claims, “Every line is the trace of a delicate gesture of the hand.”[2] I extend the statement that every gesture of the hand is the result of nature, and every force of nature is the effect of cosmic vibrations. Islamic calligraphy is a perfect example of manifesting divinity through lines and dots, which I seek to explore from an artist’s life. Always on the run, riding a motorbike from one corner of the city to another, attending to clients, informing potential students of class timings, and managing family matters, the artist embodies the art of drawing Arabic letters as a paradigmatic aesthetic experience of the Islamic tradition.

The Artist: Kashif Khan

Kashif Khan has just turned 43. He comes from the working-class town of Karachi. The area is known for ludic behaviors and humorous characters, colorful personalities, and a vibrant carnivalesque-like milieu in neighborhoods and alleys. Sufi-inspired Islam shapes the people’s religious imagination. “Our house was open for artistic activities. The local musicians used to visit our home,” says Khan. His father’s elder brother was a painter/calligrapher who designed posters and banners for commercial purposes. During the early 1990s, when Karachi was reeling from ethnic conflicts,[3] the city’s dominant ethno-nationalist political party, Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM), made them write political messages of Yom-e-Sog (Day of Mourning) in the aftermath of the killing of a political activist. The party placed these banners across the city, calling for a complete shutdown of business and everyday activities. “My uncle asked me to help him out with the banners. I used to color the banners with him,” says Kashif.

I asked him how he got into Islamic calligraphy.

A friend from the neighborhood saw me designing banners on the street. He often brought calligraphy books with him. I started taking an interest in it. We used to read and tried to understand the grammar of calligraphy from the books. Few years of engagement with the text cultivated an eye for the basic rules of writing. We decided to start designing shop billboards on Burns Road – a popular commercial area of Karachi. One day, the same friend took me to a famous calligrapher’s house. We found out the calligrapher had passed away a few years ago. However, his son allowed us entry into his father’s room, and a whole new world opened up for us. What we saw in the room was Ustad’s artistic work, which was very different from what we were designing for shop billboards. Then I decided to learn from a master.

Gradually, he started showing interest in painting and writing, and within a few years, opened his shop for designing commercial billboards. These were the days when digital technology was limited, reminisces Khan.

I kept an eye on billboards and shop names written in calligraphic styles. Some famous masters had written the signs with their hands. They were unique. I even offered a renowned ice cream shop to write its name beautifully for free. However, people are not interested in it anymore. The traditional style has disappeared from the city’s shops.

The commercial work did not satisfy Khan from the inside. It did not synchronize with the innate instincts of an artist. He felt his heart was somewhere else. Within three years of opening his own shop, he decided to close the shop and seriously pursue calligraphy. But traditional arts require a master who can cultivate the craft and wholly transform the student’s existential and ethical disposition. When we spoke, Khan usually shared stories of his teachers. A personality trait often repeated in his anecdotes is sadgi, simplicity of character. For example, Kashif Khan mentions that one of his teachers ensured that his pupils sat with him on the floor in a circle. “He finished his plate so neatly that it hardly required washing,” reminisces Khan on the etiquettes of eating.

I sought guidance from three teachers simultaneously. One taught me to write in Thuluth, the second taught me Nastaliq, and the third trained me to paint. The master who taught me Thuluth did not have any formal classroom. Every Friday after the noon prayers, we gathered around him inside a mosque where he offered classes. Sometimes we had lessons under the trees of the National Museum park near Burns Road.

He emphasizes ‘drawing’ as an underlying skill needed to become a multitalented fine artist who can dabble in different media with ease. For example, his drawing expertise allowed him to become a watercolor artist. He sold his first painting for Rs. 1,000 (approx. 16 USD). It might be clear from what I have already said, but Khan does not have a formal higher education; he was trained traditionally. At the age of seventeen, he did a short course in fine arts from a local school where he was introduced to a watercolor artist. The artist took him to an established painter, Ustad Abdul Hai (1948-2020).

In early 2000, I started visiting him at the fishing port near the Karachi harbor. It was a favorite spot for the watercolor painters. Wooden fishing boats, fishing net; the sea gave a rich material for us to draw. For the first two years, I did not draw. I just observed the teacher. Sometimes the teacher met us in the city center. We followed him as he drew the hustle-bustle of the markets. Eventually, after I started drawing, my teacher hired me to work for his studio. I made paintings for him. A few years later, I independently sold my work.

The traditional art flourishes under an intimate master-disciple relationship. Many master calligraphers do not charge any fee from students keen on learning the art of writing. The master transmits creative skills from one generation to another, forging a continuous chain of transmission of knowledge and disposition, going back to Islam’s first followers. Since it requires patience, calligraphy is slow for a fast-paced modern institutional culture, thriving on speed and acceleration. The masters ideally teach the art in an environment free from the push and pull of the anxieties and anticipations of material achievements.

The masters ideally teach the art in an environment free from the push and pull of the anxieties and anticipations of material achievements.

Someone recommended that I get a formal education or diploma in fine arts from the university. One day I went to the Department of Visual Studies at the University of Karachi. I took some of my paintings. The department chair saw my work and recommended that I do not enroll in the program at the university. She said, “You will waste your energy here.” A few years later, by God’s will, I started teaching calligraphy in the same department. I felt reinforced as a calligrapher.

As a passionate learner, Khan pursued art in many different ways. Due to a lack of state sponsorship in Pakistan, Islamic art has not flourished the way it has in Iran, Turkey, and other Arab countries.

For many years, I would visit the Quranic section of the National Museum in Karachi to learn to copy calligraphy and illumination from the old manuscripts displayed. The gatekeeper often threw us out of the gallery, but I was tenacious and kept on visiting. For hours I would observe the script, the floral design, and the paper texture. This was the only way we could watch the actual manuscript. The Internet came later into our lives, and that too was extremely slow in the beginning. It would take us hours to download a calligraphic image on the drive. We were also frightened to visit Internet cafes in the neighborhood as police raided the cafes and arrested people for watching porn or indecent acts.

A few years ago, he started an institute called Sareerul Qalam,[4] meaning the sound of a pen. “Sareer” refers to the screeching sound that comes from a bamboo pen during writing. He rented a two-room apartment in a commercial area of the upscale neighborhood of Clifton. Several female students from well-to-do backgrounds joined the art classes. I attended classes every Saturday morning. However, the COVID-19 pandemic forced him to close down the institute. During the lockdown period, he offered online courses charging a nominal fee from his students. A few of his students were from the Pakistani diaspora. After the lockdown, he again rented one room, and this time, the number of people interested in learning calligraphy increased. The lockdown has paused everyday life, opening some free space to do something different. His oldest student is a grandmother who has now mastered enough skills to display her art in a calligraphic competition.

Expressing Divinity

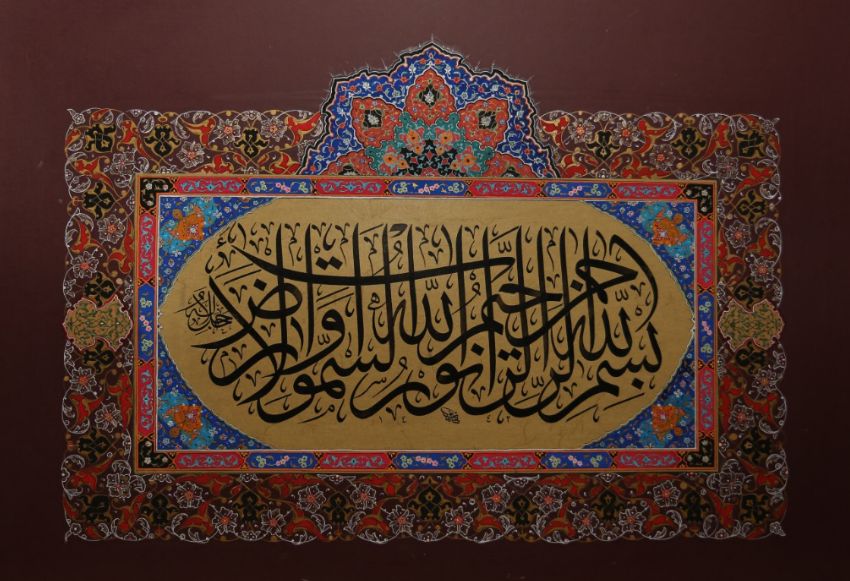

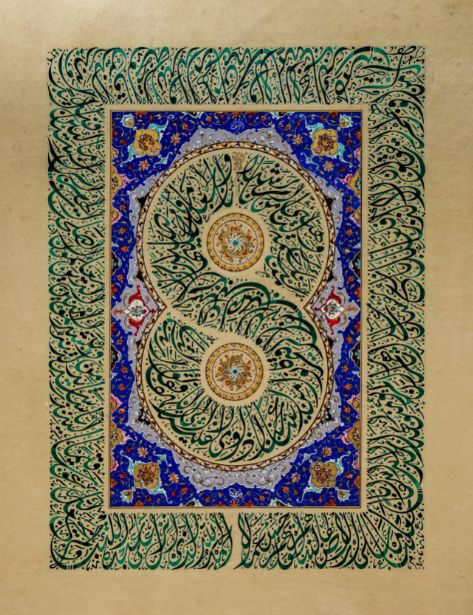

In the last couple of years, I had an opportunity to visit Makkah, Medina, and Mashhad, the resting place of Shi’i spiritual guide Imam Ali Reza, in Iran. In all three places, the Arabic calligraphy stood out prominently. The walls, ceiling, doors, and windows decorated with geometrical patterns and calligraphy indicate aesthetic significance. The tessellating design of calligraphy, each letter piercing into the other, as if tightly holding and embracing, gives the impression of continuity and strength. In contrast to Mashhad’s ornamental design, the aesthetic sensibility was austere and minimal at the sacred sites in Saudi Arabia.

Sufi-Shi’i-inspired homes are open to religious iconicity compared to Wahabi-Salafi Islam. Islamic calligraphy is decorative art. Many households adorn walls with Islamic calligraphic art known as tughra, like a cross of crucifixion in a Christian home. A popular belief that Quranic art endows God’s grace on the house makes Islamic calligraphy a popular art form in the Muslim world.

Writing holds paramount significance in Islamic cultures. Throughout the centuries, Muslim scribes and calligraphers perfected the art of writing, grounding students firmly in the art and science of letters. It combines the sacred awe and the embodied experience of letters. In addition to its artistic and spiritual dimensions, calligraphy became an integral aspect of the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal courts. “The princes and princesses did calligraphy in the old days,” mentioned a calligrapher, who tried to convince amateur students of the significance of the Islamic aesthetic tradition.

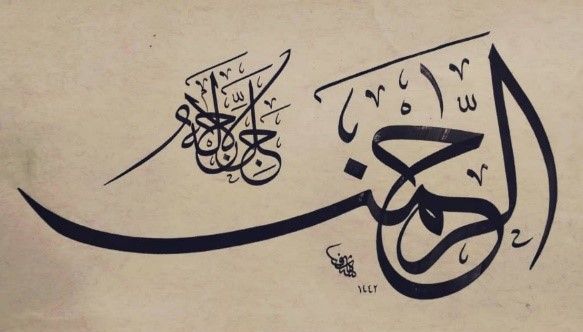

In Islamic origin myth, God created the qalam, the pen, before everything else. The 9th-10th century Persian historian al-Tabari wrote, “The first thing created by God is the pen. God said to it: Write!, whereupon the pen asked: What shall I write, my Lord? God replied: Write what is predestined! He continued. And the pen proceeded to (write) whatever is predestined and going to be to the Coming of the Hour. Then, (God) lifted up the water vapor and split the heavens off from it.”[5] The mythology surrounding the act of writing runs supreme in Islam. Often the script is represented in romantic manners. For example, “The calamus introduces the daughters of the brains into the bridal chambers of the book.”[6] In Islamic calligraphy, the qalam comes from the reed or bamboo or various other kinds of wood grown in different parts of the world. The qalam tip is then shaved to create a precise nib of multiple sizes.

Islamic calligraphy is an ancient art practiced to this day. In the early periods of Islam, 7th-8th centuries, calligraphers wrote the sacred text on papyrus and parchment. With the invention of paper, kaghaz, in China, paper became the preferred medium for writing.[7] During the 10th-12th centuries, under the Abbasid dynasty, Islamic art and philosophy flourished. Some of the brilliant calligraphers, such as Ibn Muqla, al-Tawhidi, and Ibn al-Bawwab, mastered the art of writing. Ibn Muqla, in particular, stylized the Arabic letter in perfect proportions, arresting alphabets in measured geometrical form. Ibn Muqla’s handwriting has not survived, but the following quote revealed his genius: “He is a prophet in the field of handwriting; it was poured upon his hand, even as it was revealed to the bees to make their honey cells hexagonal.”[8] Some of the sayings from 11th century documents on calligraphy extol the art as follows: “Handwriting is the tongue of the hand. Style is the tongue of the intellect. The intellect is the tongue of good actions and qualities. And good actions and qualities are the perfection of man.”[9]

Calligraphy as a Spiritual Exercise

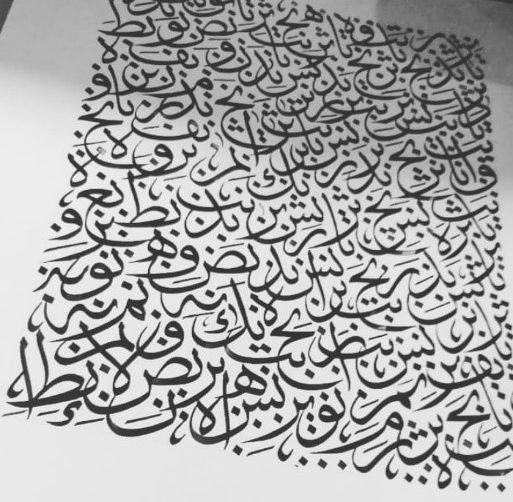

I see calligraphy as a spiritual exercise for self-fashioning the perfect proportions within a soul. It functions as an instrument for “the formation of bodily and linguistic abilities.”[10] Therefore, calligraphy, either as a ritual or spiritual exercise, cultivates inner being. It is a dialogical process: the drawing and the self-fashioning happen simultaneously.

I see calligraphy as a spiritual exercise for self-fashioning the perfect proportions within a soul.

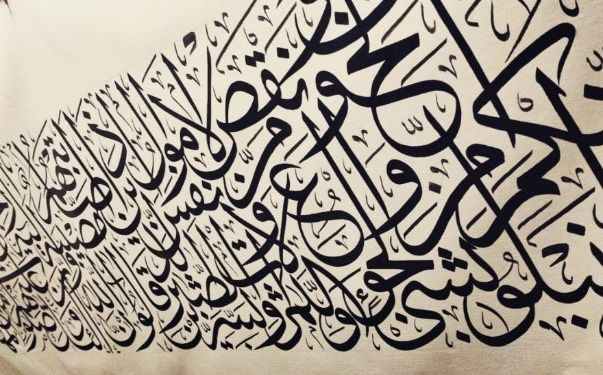

Islamic calligraphy demands submission of will, temperament, desire, thought, and muscle. The practice of writing one letter at a time or even just drawing a stroke for months builds muscle memory. Gradually, the alphabet becomes embodied, and the writing starts coming naturally. It is a kinesthetic experience, unifying bodily impulses on the nuqta, the dot – a primary unit measuring letters in symmetry. The exercise of gathering oneself on the dot unifies the senses on a common point, perhaps allowing the emergence of a point at which all senses unite.

Calligraphy is an exercise in the gathering of senses. “Don’t write. Draw. Hold your breath when drawing long lines and curves.” Khan often repeats these words when he instructs his students. Respiratory frequency shapes the letters. They are mutually co-constructing. That is why Khan often ascribes anthropomorphic attributes to alphabets, such as forbearing, graceful, gait, coquette, content, and grandeur. Each Arabic letter carries personality traits, symbolic significance, mathematical weight, and esoteric meanings. The first letter, Alif, particularly, has a more extraordinary cosmological aura in Sufi-philosophical circles. The literal meaning of Alif refers to unity, unifying, gathering, and becoming singular. Alif represents singularity, the axiomatic first principle of Islam known as tawhid, the oneness of God. The rest of the letters either emerge from Alif or are the distorted form of it.[11]

Alif represents singularity, the axiomatic first principle of Islam known as tawhid, the oneness of God. The rest of the letters either emerge from Alif or are the distorted form of it.

According to Khan, “Arabic calligraphy is slowly reviving in Pakistan. People, especially students, in various institutes are taking interest in the art.” At Habib University, incoming students often inquire about taking an Islamic Calligraphy course. This time, however, we are designing a year-long course that will offer students an enhanced aesthetic experience. In conclusion, aesthetic education –the ability to think creatively and to sense beauty– can curtail some of the disillusionment arising from a fast-paced techno-consumer world.

I thank Kashif Khan for offering his precious time, sharing the images, and teaching calligraphy.

Noman Baig is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology in the Social Development & Policy program at Habib University in Karachi, Pakistan.

1 Habib University’s Comparative Humanities program seeks to “understand and analyze the human experience in all of its complexity and range of meanings, across both time and geographic space.” For more information, click here.

2 Ingold, Tim. Lines: A brief history. Routledge, 2016, pg. 131.

3 During the 1990s, Karachi suffered a low-level civil war between different ethnic groups and state forces. Major political groups such as the Urdu-speaking MQM fought urban battles with the armed forces for the control of the city. Later, in the mid-1990s, extremist groups entered the fray and the situation got bloody. The sectarian conflict between Sunni militant groups and the Shi’a minority further escalated the situation.

4 For online or in-person calligraphy classes with Ustad Kashif Khan, contact him through Sareerul Qalam‘s Instagram page found here.

5 Rosenthal, Franz, ed. The History of Al-Tabari Vol. 1: General Introduction and From the Creation to the Flood. Vol. 1. SUNY Press, 1989, pg. 200.

6 Rosenthal, Franz. “Abu Haiyan al-Tawhidi on Penmanship.” Ars Islamica 8, no. 9 (1948), pg. 11.

7 Blair, Sheila. Islamic calligraphy. Edinburgh University Press, 2006.

8 Rosenthal, Franz. “Abu Haiyan al-Tawhidi on Penmanship.” Ars Islamica 8, no. 9 (1948), pg. 9.

9 (Ibid. 11)

10 Asad, Talal. Genealogies of religion: Discipline and reasons of power in Christianity and Islam. JHU Press, 2009.

11 For a more elaborate account of esoteric meanings of Arabic alphabets, see Ibn Al’Arabi’s “Science of Letters” in The Meccan Revelations.

I am one of Sir Kahsif’s online student, and Alhamdulillah im happy to say that Allah blessed me with such a wonderful Ustadh. He is the finest and the best Ustadh. Insha’Allah im hoping to continue learning from him till i can.

Love this article. Would love to learn arabic and calligraphy together.

Assalam o alaikum I am Rukhsana Ali, student of sir kashif khan he is a really good teacher and amazing caligrapher .As a person he is very sincere and dedicated. I feel proud that he is my teacher. TRuhank you.

Since my childhood learning from ustad kashif khan, such a human being, creative and energetic person. His passionate activities regarding art and Islamic calligraphy are unforgettable on national surface.

Taking the Kufic Calligraphy was one of the most memorable experiences as a student of Habib. Ustaad Kashif and Dr. Baig’s class shaped the direction of my thesis and I’m forever grateful for them to formally introduce me to the world of Islamic Calligraphy. What a wonderful read about Ustaad Sahab’s life!