By Layla Azmi Goushey

This piece is the first in our series on pedagogy, focused on themes of inclusivity and equity. The introduction to the series can be read here and pieces in the series will be linked in the introduction as we publish them.

I met for coffee with a friend, a retired English faculty colleague, a few years ago and after catching up on current events, we got onto the subject of our teaching methods. She had taught at my campus for 36 years, and I occupied her previous office. I described a few of my approaches to inclusive pedagogy and expressed my interest in cutting edge theories of teaching and learning. As we compared notes, I realized that my colleague had utilized many of my “cutting edge” approaches in the 1970s. “Yes, we tried that,” she thoughtfully said. I had mentioned my interest in encouraging students to write without self-criticism toward their “home” language or dialect, the natural way we all speak (and text). Writing is recursive. We can always seek feedback, self-edit, review, and revise.

At first, I was discomfited as I mulled that my cutting edge method existed 45 years earlier, but then it occurred to me that my colleague was a trailblazer. I had inherited her and her colleagues’inclusive, institutional framework. The ongoing conversation about inclusive pedagogy at my college was initiated by them. She had been at the forefront of one of the most transformational moments in education: The creation of the community college.

Between 1946 and 1947, U.S. Commissioner of Education George Zook oversaw the creation of a seminal document for U.S. higher education –Higher Education For American Democracy: A Report Of The President’s Commission On Higher Education, also referred to as the Truman Report. Included in the report, commissioned by President Harry Truman, were recommendations for establishing inclusive education and pedagogy as a foundational philosophy. These were not completely new ideas. Education theorists such as Mezirow, Dewey, Vygotsky and others had contributed to our understanding of constructivist, self-directed, student-centered learning since the late 1800s. The Truman Report, however, combined these theories with postwar social and political needs to propose a new framework for education in the United States. The report said:

We need to perceive the rich advantages of cultural diversity. To a provincial mind, cultural differences are irritating and frightening in their strangeness, but to a cosmopolitan and sensitive mind, they are stimulating and rewarding.

And

If all students are to attain common goals, much experimentation with new types of courses and teaching materials will be required. Only as these are developed, appraised, and modified to meet the widely varied abilities and needs of students in a democracy can all attain common objectives.

While some of its references and vocabulary are today dated, the Commission was firm and clear in its intent to educate for democracy, asserting that “Legislation in those States which now require segregation of white and [Black] students should be repealed at the earliest practicable moment.”

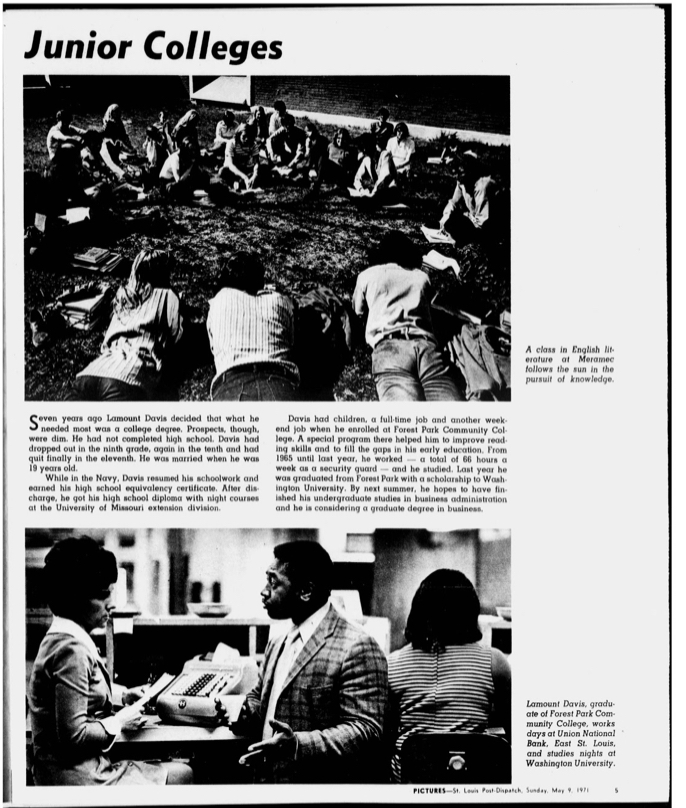

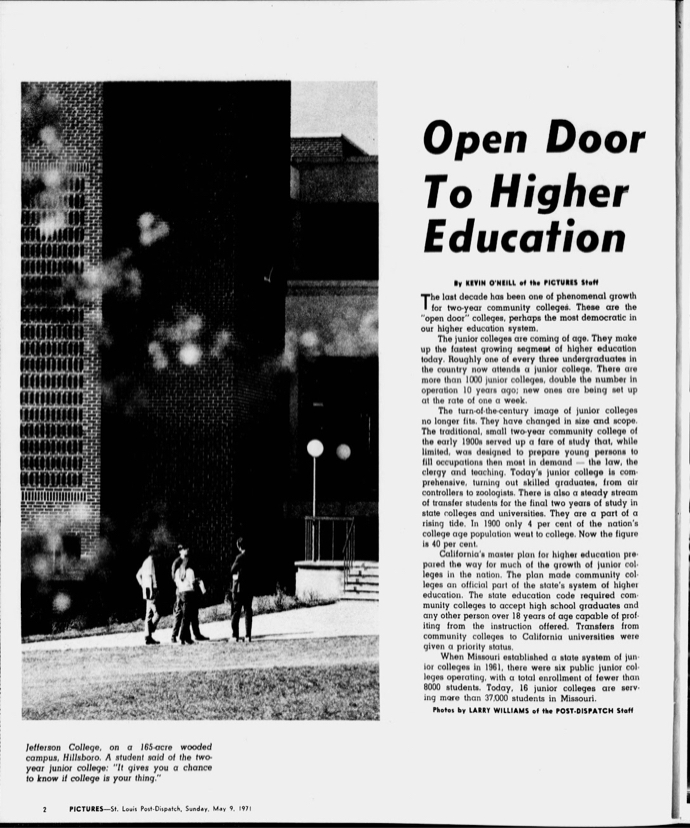

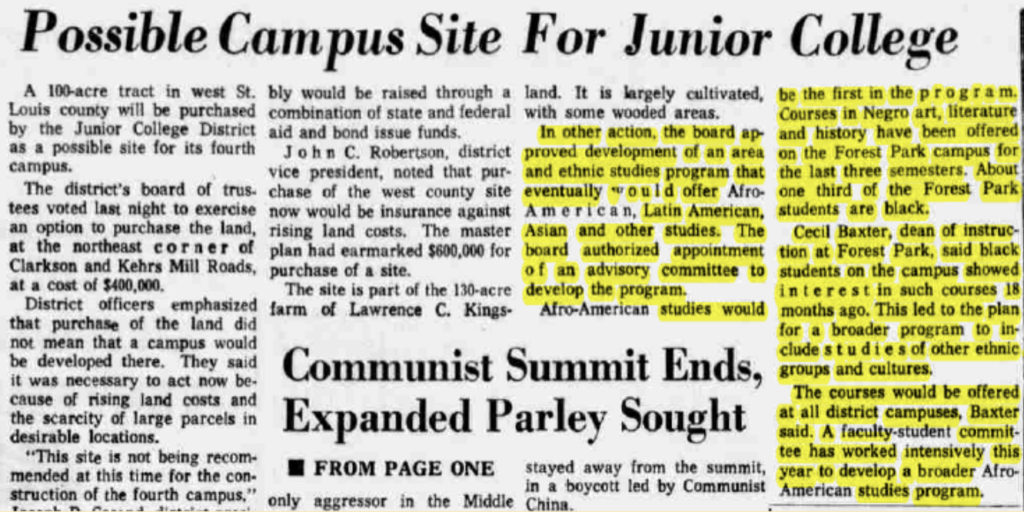

To attain these and other ambitious goals, the report proposed the expansion of junior colleges. Up until that time, junior colleges –which the Truman Reports says offered education up to the 14th grade– were operating in only a few cities across the U.S. Junior colleges originated due to the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890 (the Land Grant Act), which helped create room within land grant universities for minorities and the underprivileged. However, most education experts agreed that general education courses comprised the first two years of college, so the universities created plans for “junior colleges” and “senior colleges.” The senior colleges would focus on research and the junior-senior level of a bachelor’s degree. The Truman Report recommended that these colleges be expanded and renamed as community colleges because their mission would be to fulfill all educational needs of adults in the community. This policy became what is now known as the open door to higher education.

During a recent conversation, my colleague told me, “It was truly an open door. Students did not need a high school diploma. People were not put down for being behind in their abilities.”

Only recently have I realized how profoundly community colleges have impacted my life. As a child in Dallas, Texas, we lived near the Brookhaven campus of Dallas County Community College (DCCC). I remember walking through the halls as a teenager. I loved viewing its many student art exhibits, the quiet study areas, the busy commons area. This was my first impression of a college. It was so different from my busy, noisy high school.

The DCCC Brookhaven campus was where my Palestinian father, who did not have a high school diploma, registered to take English courses and later took automotive classes to open his own auto garage: a business that my brother still owns. My mother, too, started her path to an M.A. in International Studies at DCCC’s Brookhaven campus. I regret now that I chose to start my college education at a major university. Like many, I had the idea that real learning only happened at a four-year institution. I would have learned just as much or more in the community college’s inclusive, diverse learning environment. As a first-generation college student, I entered the four-year university with a lack of understanding of its purpose and the opportunities it offered. Most of my fellow students were from families with college graduates who understood the system. I did not apply for scholarships, grants, or other types of funding; I did not know they were available. My access to teachers and advice was mediated through teaching assistants and student volunteer advisors who gave poor advice for my purposes. I was lost. I ultimately transferred to a smaller campus of my university for my junior and senior year. The focus on mentoring and academics was stronger, but I had to make adjustments to my degree because of previous misunderstandings at the larger university. In contrast, the community college system understands that many students are first-generation and that others are non-traditional in terms of the family support they receive. Student support is more inclusive of diverse needs and mentoring is available through the faculty, advising, counseling, and student clubs.

A teacher/facilitator of inclusive pedagogy understands that students need space to discover their individual approaches to learning, and learners must learn to trust themselves and their learning styles in order to succeed. Facilitators of inclusive pedagogy are mentors to students. So, while remediation is an ongoing challenge, there are many success stories due to curricular innovations such as competency-based learning, and recursive, flexible revision opportunities. Since 1962, our college in St. Louis has served more than 1.2 million students in the region.

Teaching, staffing, and administrating at a community college is more than a career; it is a calling. As a community college professor, I received this calling when I became a writing tutor at my current institution. I was a graduate student at a local St. Louis university pursuing an MFA in Fiction, and I was a graduate assistant to the Professor of Greek Languages and Literatures. I was unimpressed, though, because I noticed that the professor rarely had time to speak to students. This was not his choice, but his administrative duties and the need to publish or perish kept him busy elsewhere. While I tried to offer moral support to students, I did not speak Greek, so I was not much help. To utilize my writing skills in a productive way, I decided to apply as a part time writing tutor at the community college near my home. After an intensive interview that comprised a full committee of eight writing center staff and faculty, I was hired. My journey in inclusive pedagogy began at the writing center.

On any given day, I would work with students from all ages and ethnicities. I coached them and offered writing assistance on their research papers and reflections on culturally-diverse and philosophically challenging readings. Because I loved this work so much, I decided to pursue a career as an English professor at the community college.

After I was hired full time, most of my professional development and informal discussions with colleagues centered on how to support learning in a classroom of students from diverse backgrounds with diverse abilities. I included materials representative of a broad range of cultures, learning styles, dialects, and abilities while also teaching academic and professional writing. When possible, I offered audio and video versions of texts so that students could approach the same reading with other versions to help them make connections to the reading. I also ensured closed-captioning of video and worked with our college access office to ensure that I understood the learning options students with dyslexia and autism needed. My approach was inspired by Lisa Delpit’s The Skin that We Speak I framed the learning of academic and professional English as an adoption of an additional code, which we switch to for specific purposes and audiences. For example, when offering revision suggestions, I discussed genre expectations with students. We discussed the word choices we use when writing to a friend versus writing to a manager in their chosen career. We examined how an article about nursing practices uses discipline-specific words that differ from articles about history or social work. I utilized constructivist assignments that encouraged students to start from their own abundance of knowledge and build emotional, affective connections to the material. I don’t remember these approaches from my own college days at the University of Texas at Austin, so I felt I was on the cusp of breaking new ground in teaching and learning.

But of course, as I learned from my colleague, the imperative to develop inclusive pedagogy today isn’t groundbreaking. Recently, I asked my colleague if she and other English faculty of the 1960s-70s were aware of the import of community colleges as a new form of higher education. She said “It was serious work. It was a mission. Mistakes were made, but we were serious about supporting students.”

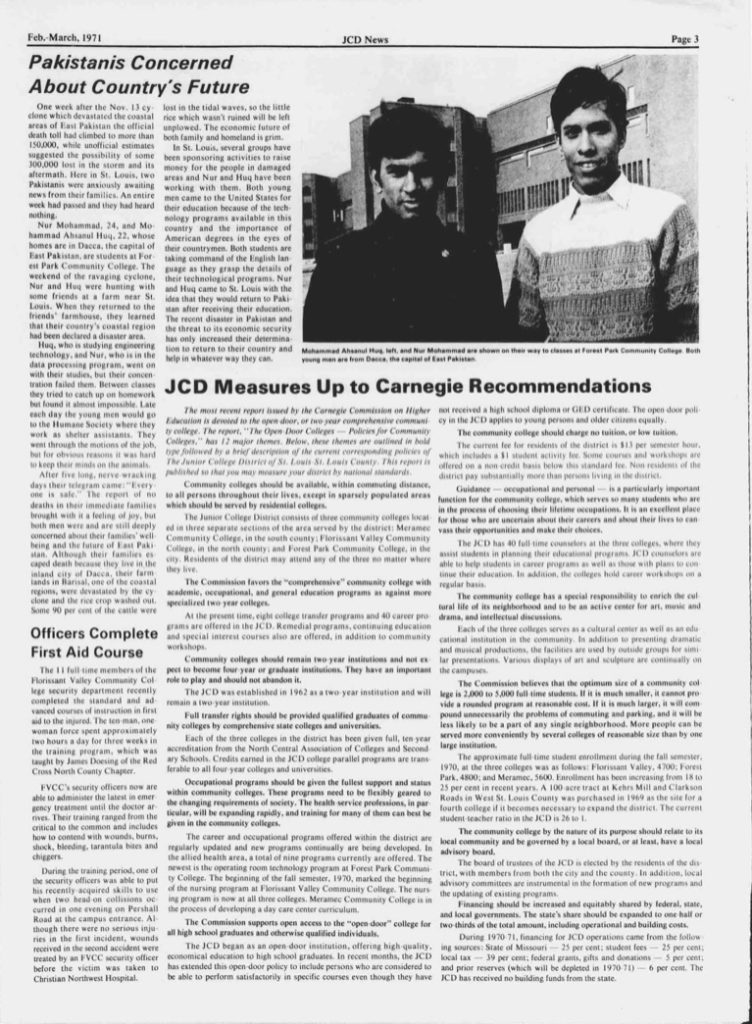

She had begun her work with college level students in Fall of 1968, at 23rd Street and Market in the city of St. Louis, on a project known as the General Curriculum. The program was funded by a grant from the St. Louis-based Danforth Foundation. The August 20, 1967 Post-Dispatch newspaper described the program:

Housewives with free time, students who need a second chance, fully-employed men and women, and students who have found that the reality of the work-world demands more education, can all find some fulfillment in the General Curriculum.

The program was described as not watered down; rather, but it was “student-centered” and “structured in such a way that the student can be helped at all levels of education.” However, the courses were non-credit, so they were meant to be preparatory for entry into college-level, credit courses. She explained that they also accepted very at-risk students who had graduated at the bottom third of their high school class. Two counselors were included in the program that offered basic studies in reading, writing, and math along with courses on sociology, the humanities, and other courses to help the student “understand himself, the society, and his times.” There was also a “Who am I” human potential seminar along with counseling sessions to address the affective domain of learning.

My friend noted that the philosophy of the 1960s-70s teachers was that “everyone deserves a chance.”

The program developers made sure to hire a diverse faculty. At least one half of the faculty in the program were black. However, the program was not a success. Students did not want remedial, non-credit courses.

My colleague explained that the 1960s-70s English faculty on my campus had what we would now consider a constructivist, culturally-responsive, inclusive pedagogy. She said, “The method was ‘Just start in English. We will work with you. We don’t want to slow you down.’” Some students, aware of the difference between their dialect and academic norms, had the perspective that It’s mine and I’ll write it that way. Even many of the faculty felt that “fluency and flexibility were important, but the five paragraph essay was too white.” In total, she says, “there was a lot of politics involved.” For example, the phrase He be working was recognized as a vernacular phrase and was considered just as good as He is working. One practice the English department sought to overcome was the self-regard of tracked students. As my colleague noted, “IQ tests were offered in 5th grade, and after that students were tracked as intelligent or not.” We are still contending with similar challenges today. Ferguson, Missouri, the focal point of the new phase of the civil rights movement, is located in St. Louis County. Many of my students live near there and the problems with low-performing schools, poverty, and corrupt police municipalities contribute to the same challenges students in St. Louis faced 50 years ago. However, lack of preparedness for college is an historical problem but not specific to only the St. Louis region. As Dr. Jill Biden – First Lady of the United States – explains in her dissertation Student Retention in the Community College: Meeting Students’ Needs:

The logical conclusion is that high schools are graduating students who are ill prepared for the rigors of college. Yet the problem is much more complex than that. Many community college students were not enrolled in college preparatory programs in high schools; many come from vocational educational programs for which community college is a logical step. Many are older students who have returned to school after having children or changing careers and are seeking upward mobility. Others may have dropped out of high school. The reasons are numerous, yet the gaps in education are pervasive. The State of Delaware is small enough that for students who are matriculating from high school to Delaware Tech, the transition should be almost effortless….. Yet, too often, they struggle and fail.

What we know for sure is that over 90 percent of U.S. adults have a high school diploma, 49 percent have an associates degree, and 39 percent have a bachelor’s degree. What is also clear from low retention rates at many colleges and universities is that a large number of high school graduates are not socially prepared for college. They do not have social and economic support for their goals. The result is that many enter adulthood working in lower-wage industries when they may be qualified to do more.

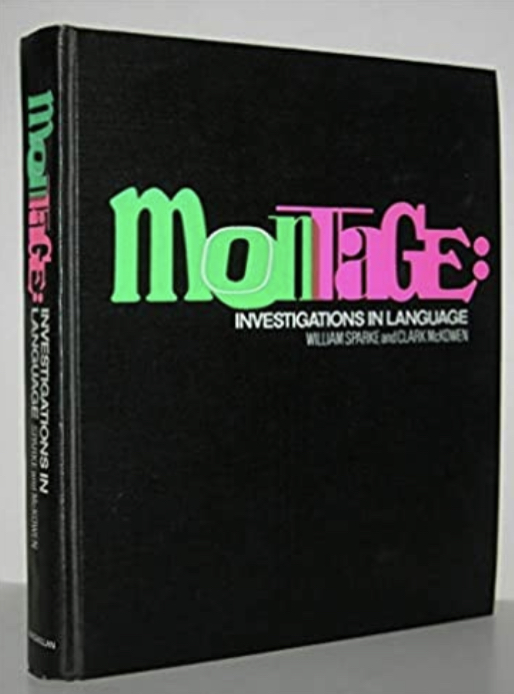

But I asked my friend “what about an inclusive curriculum? Could students find themselves within their readings and assignments?” She says, “The Montage English textbook. That was hip.” The textbook framed assignments within a theory of language awareness with diverse authors in literary fiction. She also used James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time in her literature course. I was struck by the inspiring thought that her students were contemporaries of Baldwin.

She says, “We were the first ones to hold the standard. At my campus, racial awareness was up front. A student’s average age was 29. There were students with children. The English department was very supportive of the Black Student Union.”

So, what lessons can be learned from the knowledge that community colleges have continuously applied inclusive teaching and learning strategies over the past 50 years? To paraphrase my friend and colleague: It is serious work. It is a mission. Mistakes are made, but we are serious about supporting students.

The faculty of nascent community colleges had passion. Fifty years later, we still do.

Layla Azmi Goushey holds a Ph.D. in Adult Education: Teaching and Learning Processes and she is a Professor of English at St. Louis Community College in St. Louis, Missouri. Her dissertation examined the teaching perspectives of university faculty members in the Arab region. She is a poetry and non-fiction reviews contributor for Sukoon Magazine, an Arab-themed art and literature journal. Her poetry and prose have been published in several literary journals. She has recently published two essays: “The Jordanian Kids” in the June 2019 St. Louis Anthology and “Profile of a Citizen: Generations Then and Now” in the March 2020 anthology, Beyond Memory: An Anthology of Contemporary Arab American Creative Nonfiction.

Recommended reading: This list is not exhaustive, but these books and articles have informed my thinking about Inclusive Pedagogy. The first two books on this list offer specific teaching and curriculum-building strategies; however, Inclusive Pedagogy is informed by context. Most of these recommendations offer perspectives on the conditions students and educators encounter in social and educational settings.

Teaching Strategies and Curriculum Building

The Skillful Teacher by Stephen Brookfield

Contextual Understanding

Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope by bell hooks

Savage Inequalities by Jonathan Kozol

Uncivil Rights: Teachers, Unions, and the Battle for School Equity by Joanna Perrillo

Lives on The Boundary by Mike Rose

Community Colleges and the Access Effect: Why Open Admissions Suppresses Achievement Authors: Scherer, J., Anson, M. —>My Review

Theoretical Foundations

Democracy and Education by John Dewey