Written by Chris Gratien and Daniel Pontillo

Digitization is changing historical research, and few digitization projects have done more to revolutionize the way we write history than Google Books. This project, in partnership with a number of libraries, has rendered once rare and difficult-to-access printed books increasingly ubiquitous commodities available for download through Google and partner sites such as Hathitrust. This has multiplied the value of rare books that once slumbered in the obscurity of research libraries. Now they can be searched and consulted with unprecedented speed and used to form corpora of historical, cultural, and linguistic material. The change is not simply about accessing more data; it is about new ways of organizing and interpreting that data afforded by its new digital form. The Google Books Ngram Viewer is one important example of how digitization can transform the types of research questions asked and answered in the social sciences and the humanities. It features a simple web interface to Google’s rich database of scanned texts from centuries of publishing in English, as well as other languages, such as French, German, Spanish, Italian, Russian, Hebrew, and Chinese.

For researchers enticed by this description but unsure what an n-gram is or how to use it, we offer this brief introduction. An n-gram is simply an instance of a word or phrase within a corpus, where n is a variable representing the number of words. Google’s service allows researchers to track the relative frequency of n-grams over time and generates plots (called T-transformations) to illustrate and contrast the usage of words and phrases over years. While the causal link between language use and the statistical patterns found in published materials is not necessarily linear, Ngram can offer a window into shifts in human language and society by substantiating putative trends formerly described only qualitatively and offering new questions and potential areas of inquiry, particularly when interpreted within an informed historical context.

Ngram has yet to make a big splash among academic historians, who are perhaps less accustomed to using and evaluating statistical data than linguists. However, given that Ngram draws on the very sources used by historians and has the power to represent information about them in a diachronic manner, we believe that it has much to offer researchers. Moreover, the visualization of this data presents in supremely legible form a representation of important historical points that make Ngram ideal for classroom and conference presentations.

Yet, at the same time, just as digitization has created the potential for “cherry-picking” data from searchable texts without proper care for context, Google Ngram has the power to mislead scholars that ask the wrong questions. In order to elaborate further on the benefits and hazards of the Google Ngram viewers, we will start with a basic “historian’s example” of how Ngram can be used and follow with an example from linguistics that demonstrates how to make the most of Ngram searches.

A Historian’s Example

When writing the history of disease, it is relatively easy to formulate a narrative based on dates marking certain influential medical discoveries. For example, in the case of malaria, we know that Charles Laveran identified the parasite that causes malaria in 1880 and Ronald Ross first identified the parasite within the mosquito in 1897, which subsequently led to the discovery that mosquitos transmit malaria between humans. Yet, this tells us little about how understandings of disease changed over time, and how former notions regarding disease persisted alongside new ones.

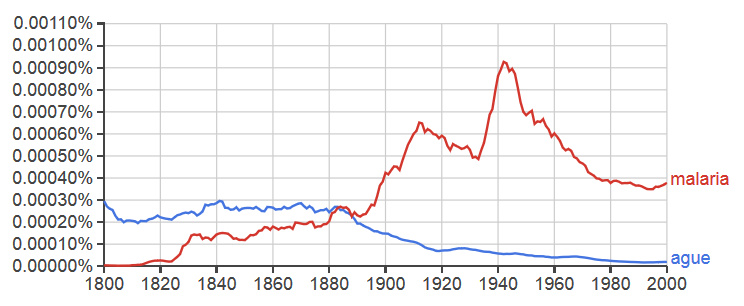

One of the challenging questions faced by disease historians is thus how to represent changing understandings of disease quantitatively rather than with anecdotal evidence. Google Ngram offers one possible avenue. Malaria is a relatively new term in the English language that nonetheless predates the aforementioned discoveries. Its etymology is rooted in medeival Italian mal aria (bad air) and refers to the idea that the disease was caused by dirty emanations from swamps and rotting organic matter. However, the term malaria became the standard way of referring to the disease only after the discovery of the parasite. Before this, there were various ways of referring to the unique symptoms of recurring fever and chills associated with malaria.

The above n-gram diachronically charts the relative prevalence of two words roughly referring to the same illness in the English language. The first, ague (a-gyu), is now an exceedingly rare term that few English speakers would recognize today. Variations of this word were once common in a number of European languages. It comes from the Latin term for “acute fevers (febris acuta)”, the most glaring symptom of malaria. The second, is the word malaria universally applied today in reference to that illness in English. The graph shows the respective fates of the two terms over the centuries. The term malaria began to spread during the early nineteenth century and rose in importance, we presume, due in part to medical research and writings on its causes and effects. The two terms were of nearly identical importance in 1880 when Laveran first discovered the parasite. Following this discovery, we see a rise in the occurrences of malaria in written English (Laveran in fact used paludisme which became “paludism” in English). Use of the word malaria peaked around the World War II era, when malaria was a major killer among Allied military personnel in the Pacific theater and research into the use of DDT in combating the illness was at its height. Meanwhile, ague continued to wane as the cause and symptom of malaria were merged. However, its use lingered in the intervening decades, representing the remnants of past understandings of disease. This n-gram shows a similar trend in the medical vocabulary of the French language, indicating an epilinguistic phenomenon regarding understandings of disease.

In the above case, we have used n-gram to represent graphically a trend that was already vaguely understood but hard to visualize in a quantitative manner. The n-gram does not necessarily make the discovery on its own, but it certainly helps us to strengthen our claims. We can also use Google Ngram Viewer to stimulate new questions. For example, we might ask how the rise of medical science has led to a shift whereby diseases are increasingly identified according to their cause rather than their symptoms by making similar queries for other well-known diseases. Yet, here we must note that Google Ngram raises more question than it answers. To illustrate the benefits, limitations, and hazards of Google Ngram further, we will delve into the contentious and vogue issues of identity, labeling, and political correctness.

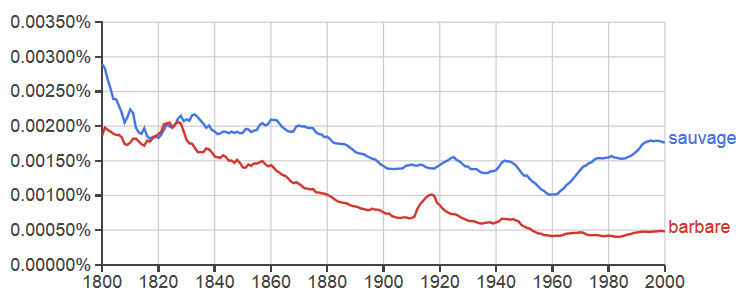

Upon seeing the types of data that Google Ngram Viewer can visualize, many historians will probably begin by searching for new or old words related to their topics of study, for example, juxtaposing “Native American” with “American Indian” or putting “Moslem” and “Muslim” side by side. Such searches can result in some surprising indications that encourage further inquiry. The two plots above show the use of the word “savage” and “barbarous” diachronically, with English being on the left and the French translations “sauvage” and “barbare” on the right. While these pairs are good translations for each other, we must acknowledge that they may not be used in identical ways in both languages. They also serve as multiple parts of speech, but Google can account for that (see below). It is also important to note that comparing results from different corpora is statistically problematic because the overall size, the relative quantities of certain document types and distribution of topics in the source materials may differ dramatically. Any statistical biases that result from such differences in the distribution of sources can skew the results. Due to the very massive size of these corpora, the results should nevertheless give us a rough illustration of an underlying trend. In this case, the plot suggests that the word “savage,” which was more commonly mentioned in English than “sauvage” in French ca. 1800, has steadily declined in usage, particularly after 1900. Given the politically incorrect connotations due to its association with various forms of racism and cultural superiority as well as colonialism, this seems intuitive to us. Yet, what is then harder to explain is the parabolic rise and fall of “sauvage” in French, which apparently enjoyed an uptick at the end of the 1950s, precisely as colonialism was on the wane.

These graphs may inspire us to ask further questions; however, they may also be used to illustrate the perils of using n-grams to speculate about sociolinguistic phenomena. For example, if we try to interpret this data in terms of its extra-linguistic meaning, we might say as is commonly and anecdotally observed that the French language has not been impacted by a movement towards political correctness in the same way that English has. While a discussion of these graphs in terms of those questions may make fun and interesting table conversation at Franco-American get-togethers in New York and Paris alike, this is an example of reading something into Google’s data that it simply is not equipped to tell us (just search for even less politically correct words in Ngram and you’ll see data that further proves our point). The message to historians seeking to utilize n-grams is simply that as in all studies of history, unsystematic evaluation of evidence and lack of consideration of contexts will lead to mistakes. The comparative study of political correctness would certainly be a fascinating one, but Google Ngram will not be able to do all the work. Yes, you will still have to read books. Fortunately, Google has digitized many of them!

All of this being said, it is also helpful to remember that Google Ngram utilizes a linguistic corpus organized according to the standards of modern computational linguistics, which is to say that for historians to maximize the utility of n-grams, they will benefit from acquaintance with the ways in which linguists put them to use. Learning what the data represents and how it is intended to be used will both enable researchers to ask more precise question and extract more meaning from their searches.

A Linguist’s Example

Just as digitization tremendously impacts historiography, the horizon of linguistics research has shifted considerably due to the massive increase in availability of language use data in the past several decades. This rise in availability has been accompanied by advances in quantitative methods that permit the statistical patterns in records of human language to be investigated with unprecedented empirical rigor. Linguists now use corpus data to explore questions about language use ranging from raw lexical or phrasal occurrence frequency to patterns in syntax, word meaning, pragmatic interpretations and discourse structure.

These tools are of course not without limitations. Large pools of linguistic data are difficult to organize, and the types of testable hypotheses are tightly constrained by the level of annotation that accompanies the raw data. In this context, annotation can be as simple as tagging each string with its part-of-speech (POS)—a technique known as automatic probabilistic tagging, or it can be as complex as encoding texts into abstract tokens and embedding them in formal representations of discourse structure. As an example, The Penn Tree Bank, the first widely used annotated corpus, offers basic syntactic and semantic information about its constituent sentences. There are also newer specialized corpora such as The Proposition Bank, which is annotated with the semantic role of verbs, allowing for the automated distinction of agent/patient status that would otherwise be conflated by POS alone.

Part of what makes the Google Ngram Viewer so useful for linguists is the same benefit offered to historians, which is that unlike most of the annotated corpora currently available, it offers the option for exploring diachronic questions. The organization of language use data by year opens a category of inquiry about language change that was previously much more speculative. Before Google Ngrams, there were a handful of comparatively small and temporally limited corpora such as the The Diachronic Corpus of Present-Day Spoken English and the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). It should be noted that Google’s corpus, while much larger than these, lacks their breadth of unique tokens due to its hard lower threshold on occurrence; it only includes results that occur at least forty times. This leaves precise questions about the origins of novel words or phrases unanswerable, and it prohibits any type of inquiry about rare constructions or very low-frequency words. Nonetheless, the sheer volume and temporal range of the corpus offers unique advantages for certain types of research.

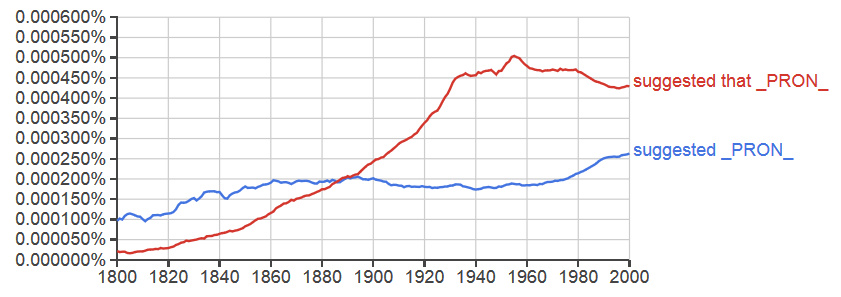

As discussed above, historians might find Ngram useful for exploring the history of certain concepts or identifying historical fluctuations in the importance of topics, but what types of questions would a linguist ask? One typical question about language use that might be asked with Google n-grams regards the historical shift in English complementizer drop patterns. The examples below illustrate how the complementizer “that” may be dropped in many English constructions.

1. Chris knew (that) he would relent on his promise.

2. Kellen thought (that) they wouldn’t mind watching him eat his dinner.

Exploring this issue will require more specialized searches than those conducted above. Fortunately, Google Ngram Viewer allows us to look at the relative frequency of these two possible constructions across nearly two centuries of language use data. The plot below shows the result of this comparison for a particular verb (suggest) that may take a complementizer phrase as an argument.

This change and crossover between the two plots shows us that the typical syntactic pattern for this particular verb underwent a significant historical shift. Collecting trends of this type across different classes of verbs might offer some insight into the pressures underlying this change more generally. This type of shift may for example correlate with known historical events or the rise and fall of publications aimed at certain social registers.

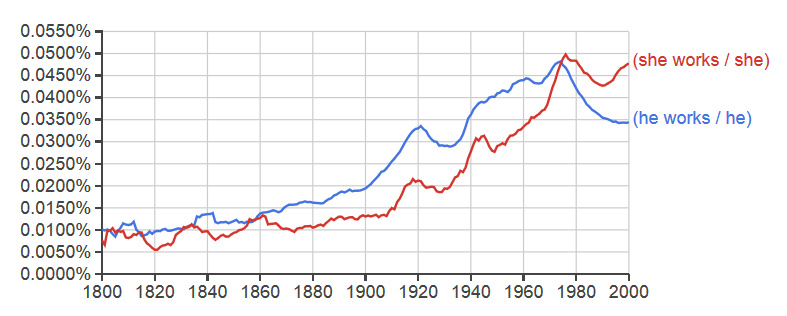

The value of this tool for linguistics researchers is evident, but we would like to stress that making use of basic syntactic information included in Google Ngram’s corpus can benefit social scientists as well. Certain questions couched in language change may offer intriguing insight into changes in cultural trends and standards. The plot below effectively contrasts the proportion of all instances of the pronoun “he” that were followed by the word “works” to the proportion of all instances of the pronoun “she” that were followed by the word “works”. Google Ngram’s division operator allows us to compute these ratios very easily. This measure roughly represents how often, when discussing either a female or male subject, the subject was described as working. Using this more complex n-gram query, we can ask about the relative change in discussion of female work while ignoring the well-known baseline bias for male subjects in published work. We can read the rise in frequency of the feminine phrase as a rise in published discussion of female behaviors as “work” and hence a sort of rough proxy for the increase in socio-cultural normativity of female employment at least within the domains of constituent texts. It is also interesting to note the visible trough in frequency for both bigrams that chronologically coincides with the Great Depression.

While Google n-grams may lack the type of granularity necessary for detailed network-level analysis and fine-grained modeling of language change—and one must resist the temptation of presuming strong causal links where there is only correlation, these examples illustrate the breadth of inquiry that is possible. The sheer size and availability of this tool make it a potentially indispensable resource for research in any field where the use of language might reflect broader aspects of human behavior, such as in psychology, linguistics, history, or anthropology.

The Need for Digitization

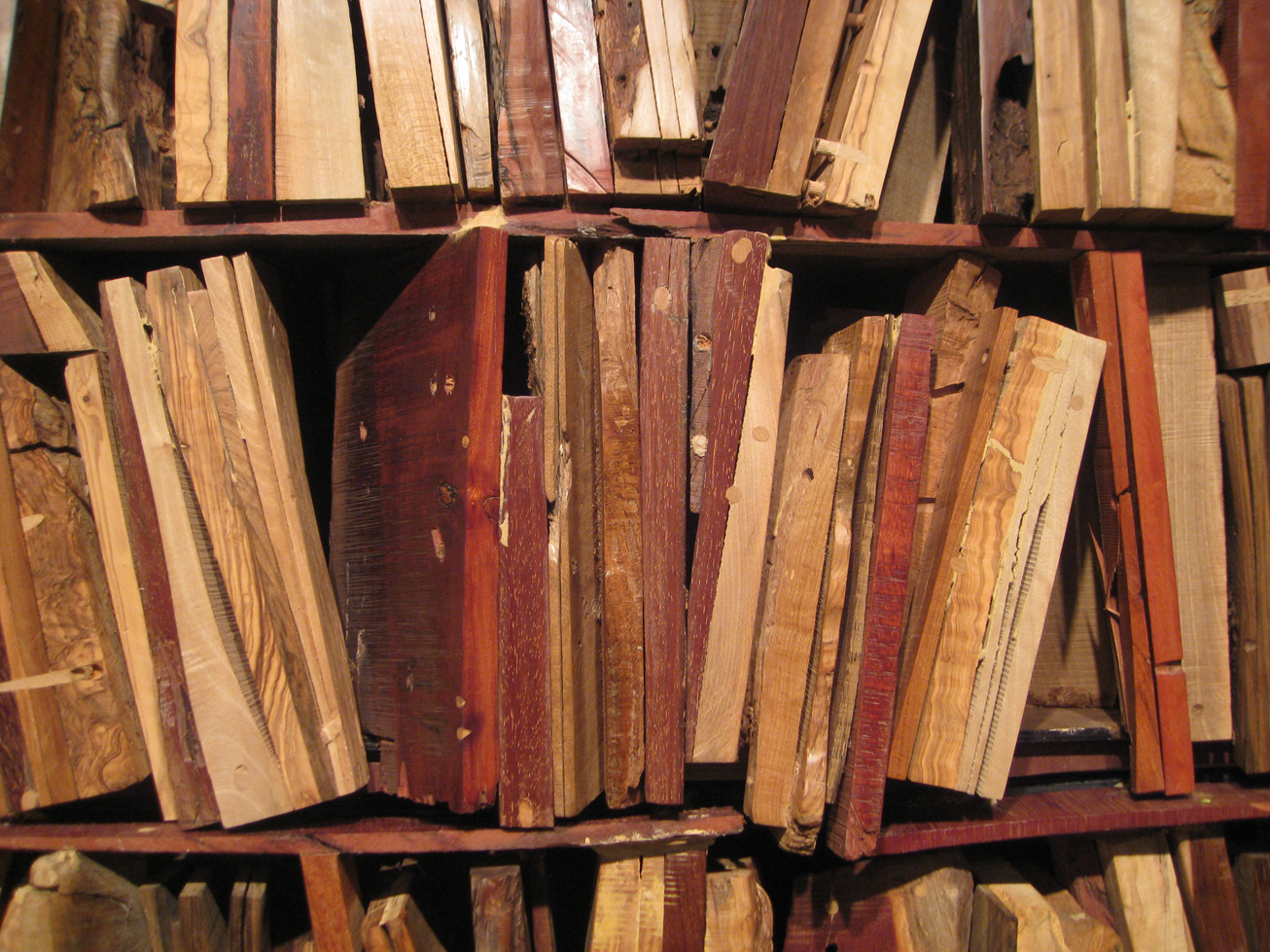

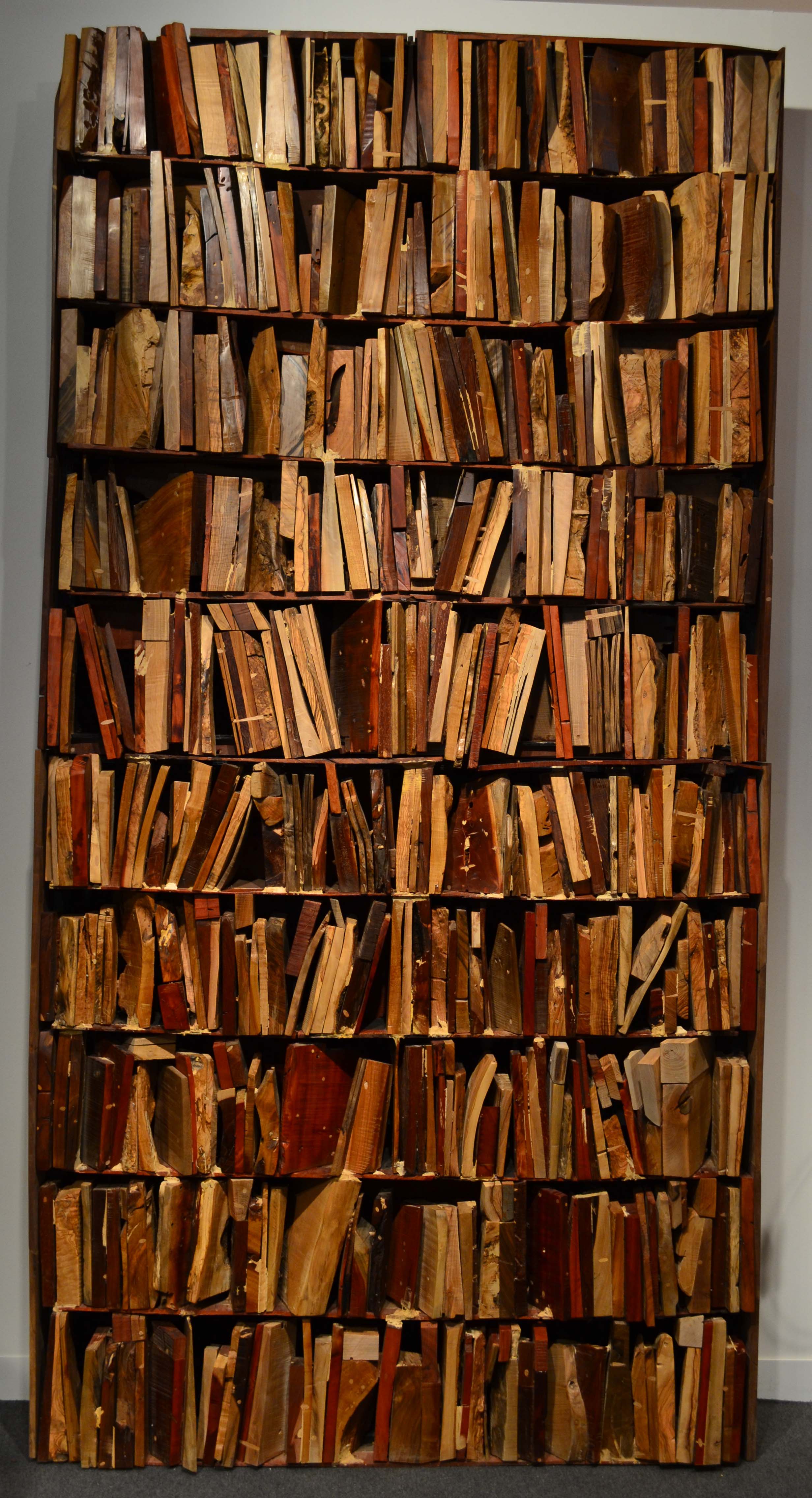

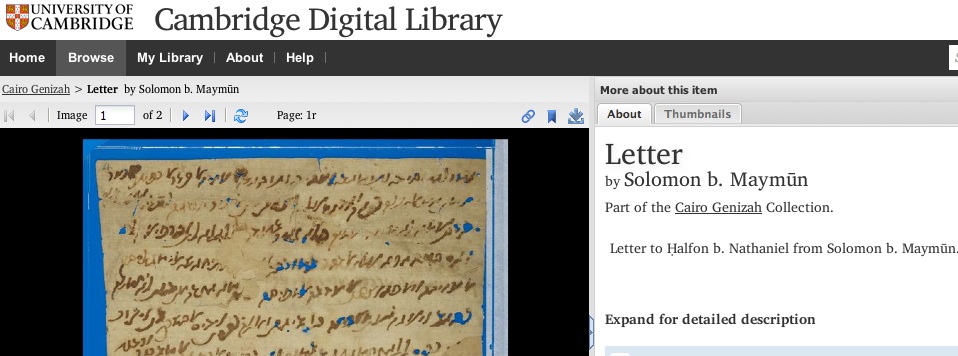

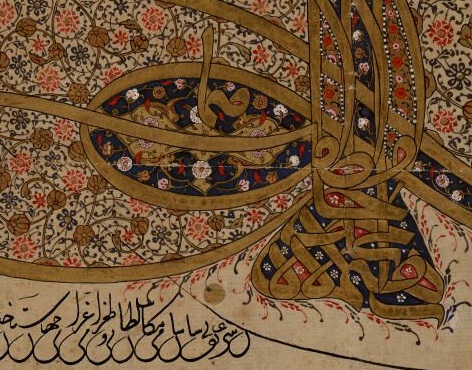

In many ways, Google Ngram Viewer further substantiates what has increasingly been argued within the social sciences and humanities since the linguistic turn. Conceptual categories are not stable, and n-grams not only support this claim but also offer ways of studying even the most subtle changes in word use and conceptual nuance through mark-ups that allow researchers to control for the frequency of words in different parts of speech. Yet, it also reveals some disconcerting realities among various fields of study from anthropology to linguistics that have long railed against the reification of Eurocentrism and the universality of the “Western experience.” The Google Books corpus is formed out of the holdings of American libraries and limited by the constraints of current OCR technology (which is for the most part only widely available for European languages). Historians of the Ottoman Empire will find this tool considerably less useful than those who study US or Mexican history, and those who want to make comparative studies will be forced to remain within this Western context.

However, if we assume that the Google Ngram Viewer is not the first and last of its kind, this tool portends an exciting future of corpus-based analysis. As OCR technologies improve to encompass handwritten texts to counteract the biases of a solely print-based representation of linguistic change, the conclusions we can make will grow stronger. This development further emphasizes the utility of digitization projects, and we wish to stress that in regions of the world such as the Middle East where market forces may not push the development of sophisticated OCR, public or private funding for digitization and the expansion of text-recognition will be critical to securing the place of important historical languages such as Arabic or Ottoman Turkish within the growing corpus of human linguistic data.

__________________________________________________________________________

Chris Gratien is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at Georgetown University researching the history of disease and ecology in the Ottoman Empire.

Daniel Pontillo is a doctoral student in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at University of Rochester.

11 January 2014

Cite this: Chris Gratien and Daniel Pontillo, “Google Ngram: an Introduction for Historians,” HAZİNE, 11 January 2014, https://hazine.info/2014/01/11/google-ngram-for-historians/