Written by Sanja Kadrić

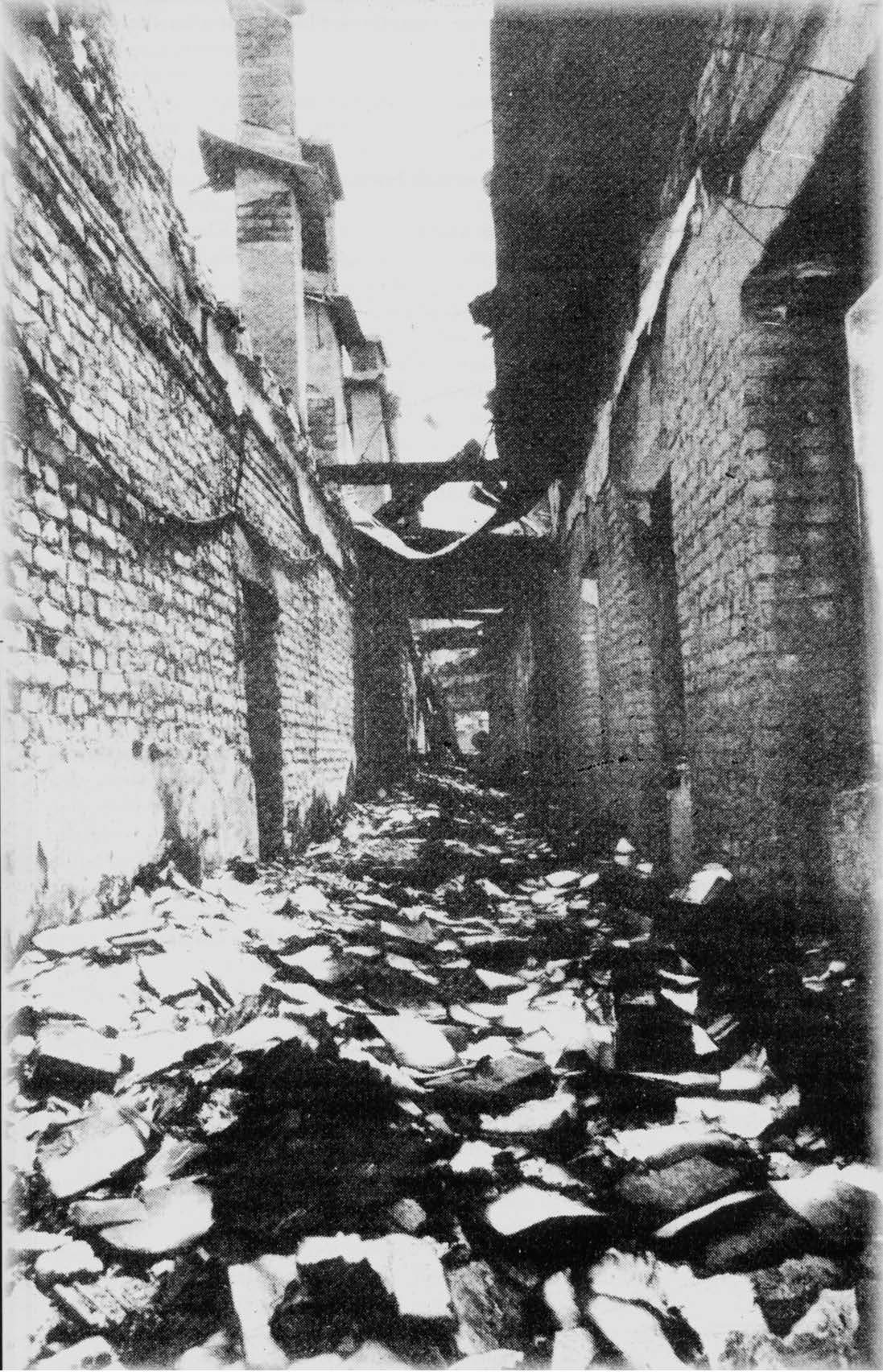

The Bosniak Institute (Bošnjački institut – Fondacija Adila Zulfikarpašića) is a foundation established to promote the development and preservation of the cultural wealth, history and identity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Institute offers a large, multi-themed library, a manuscript and rare books collection, an archive, and various special collections such as those of postcards and audio records. Such wide-ranging efforts to preserve the cultural and historical heritage of Bosnia are quite significant, particularly in light of attempts to destroy Sarajevo’s libraries and archives during the war between 1991 and 1995. This institution will be of great interest to all those researching Bosnia and Herzegovina, the former Yugoslav republics and the Balkans at large, as well as the various peoples, empires, religions and cultures that interacted with this region.

History

Bošnjački institut – Fondacija Adila Zulfikarpašića is a vakuf of the late Adil-beg Zulfikarpašić, a prominent and well-esteemed Bosnian politician, philanthropist, intellectual and patron of the arts. He and his wife Tatjana Zulfikarpašić devoted decades to meticulously collecting and cataloging literary, artistic and archival materials on the cultural heritage and history of Bosnia and Herzegovina, former Yugoslavia, and the surrounding region. Originally established as the Bosniaken Institut of Zürich in 1988, the institute’s purpose was to promote and preserve the cultural, religious and linguistic wealth of the many peoples living in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bosniaks in particular. The Institute opened a branch in Sarajevo in 1991 and moved there completely in 1998, officially opening in 2001. Its many collections continue to grow and expand through private donations as well as new acquisitions on the part of the Institute and vakuf.

Collection

The Institute offers researchers monographs, reference works, periodicals (newspapers and magazines), a rare books collection, a map collection, a photographs-and-postcards collection, an archive, audio-visual records and an Oriental manuscripts collection.

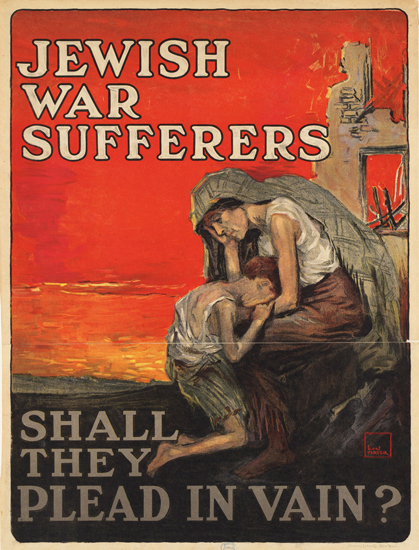

The library holds over 150,000 works dating from the sixteenth century to the present day. These holdings are divided into the departments of Bosnika, Kroatika, Serbika, Jugoslavika, Emigrantika, Islamika, Balkanika, Turcica, and Judaica (Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, Yugoslavian, Emigrant, Islamic, Balkan, Turkish and Judaic) with special sections devoted to the Bogumils, agrarian reform, the War of 1991-1995, the Sandžak region and reference materials. The Bosnika department is the library’s largest and contains works on Bosnia and Herzegovina and its peoples and history in a wide array of languages and themes. The Emigrantika department features works published by the region’s diaspora throughout the world following World War II. The department of most interest to the readers of HAZINE, however, will probably be that of Islamika which contains works in Arabic, Turkish and Persian on various themes such as history and natural sciences as well as encyclopedias and commentaries on the Qur’an.

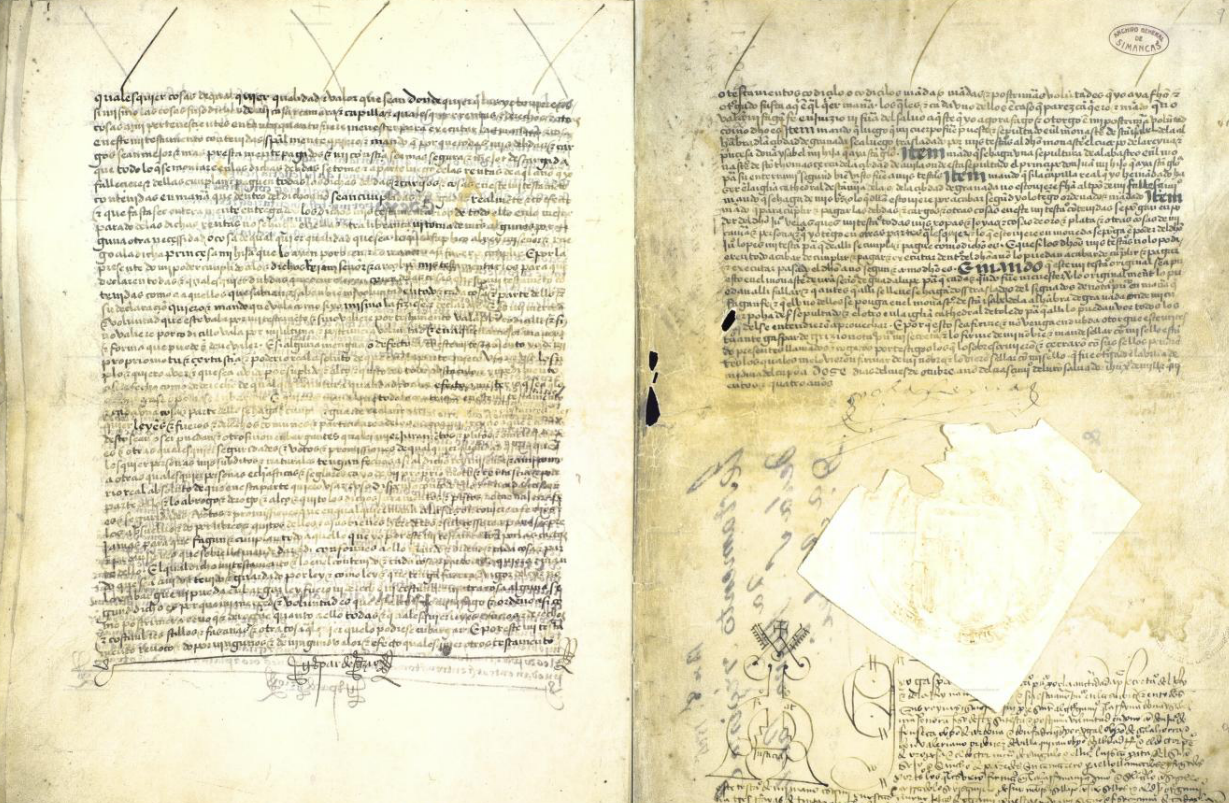

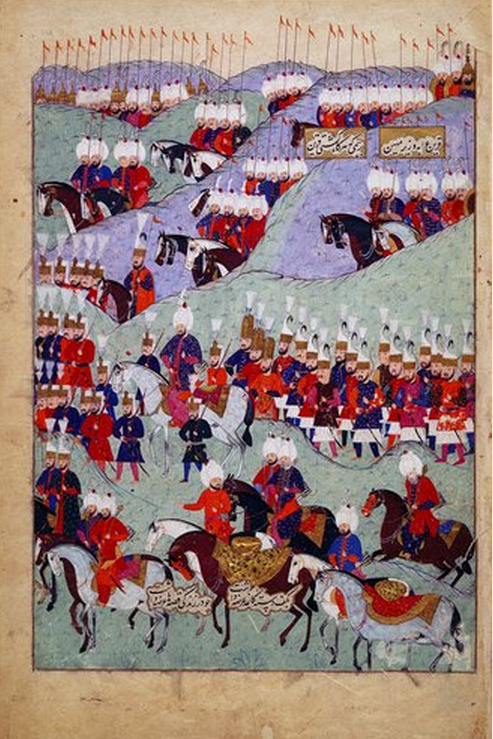

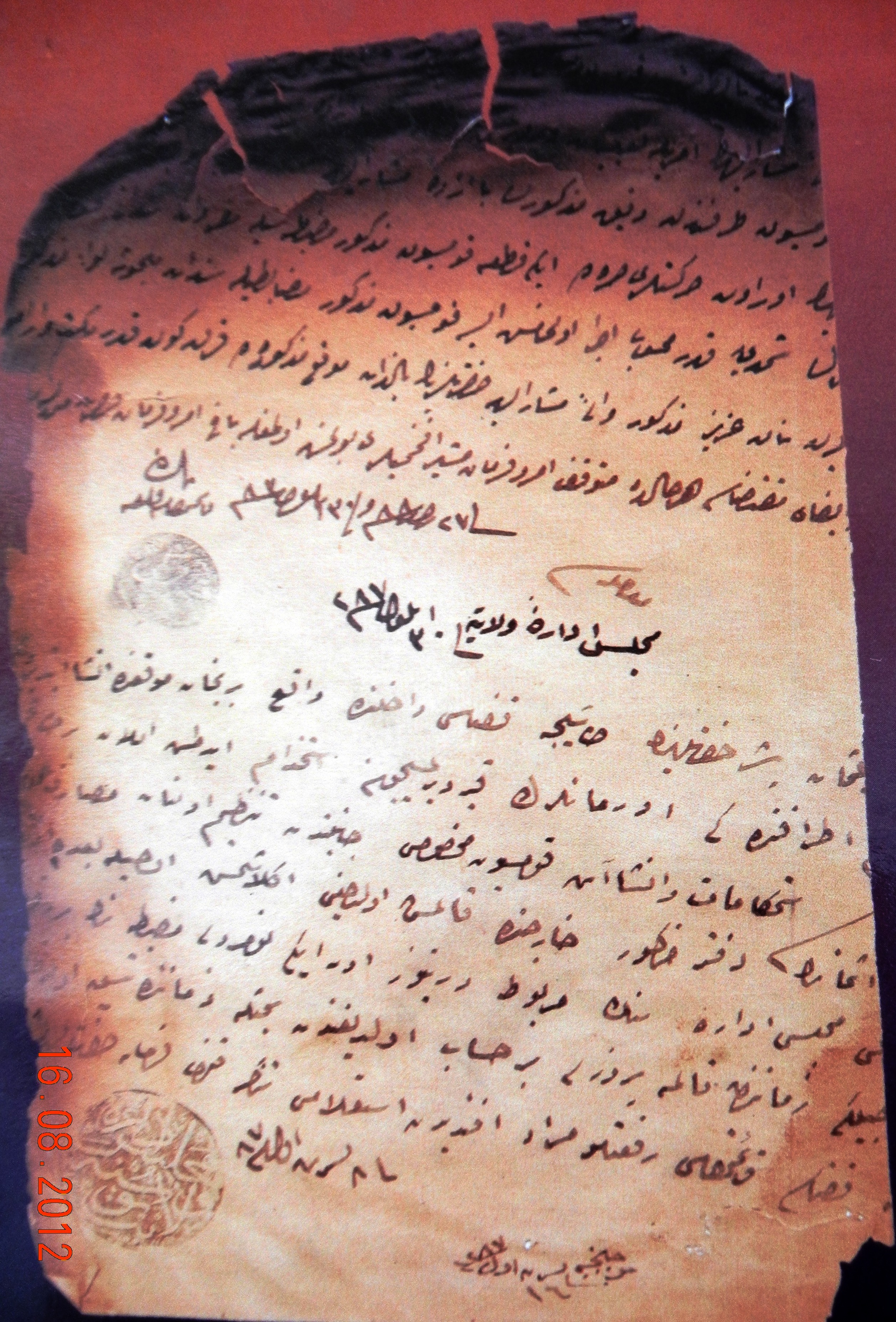

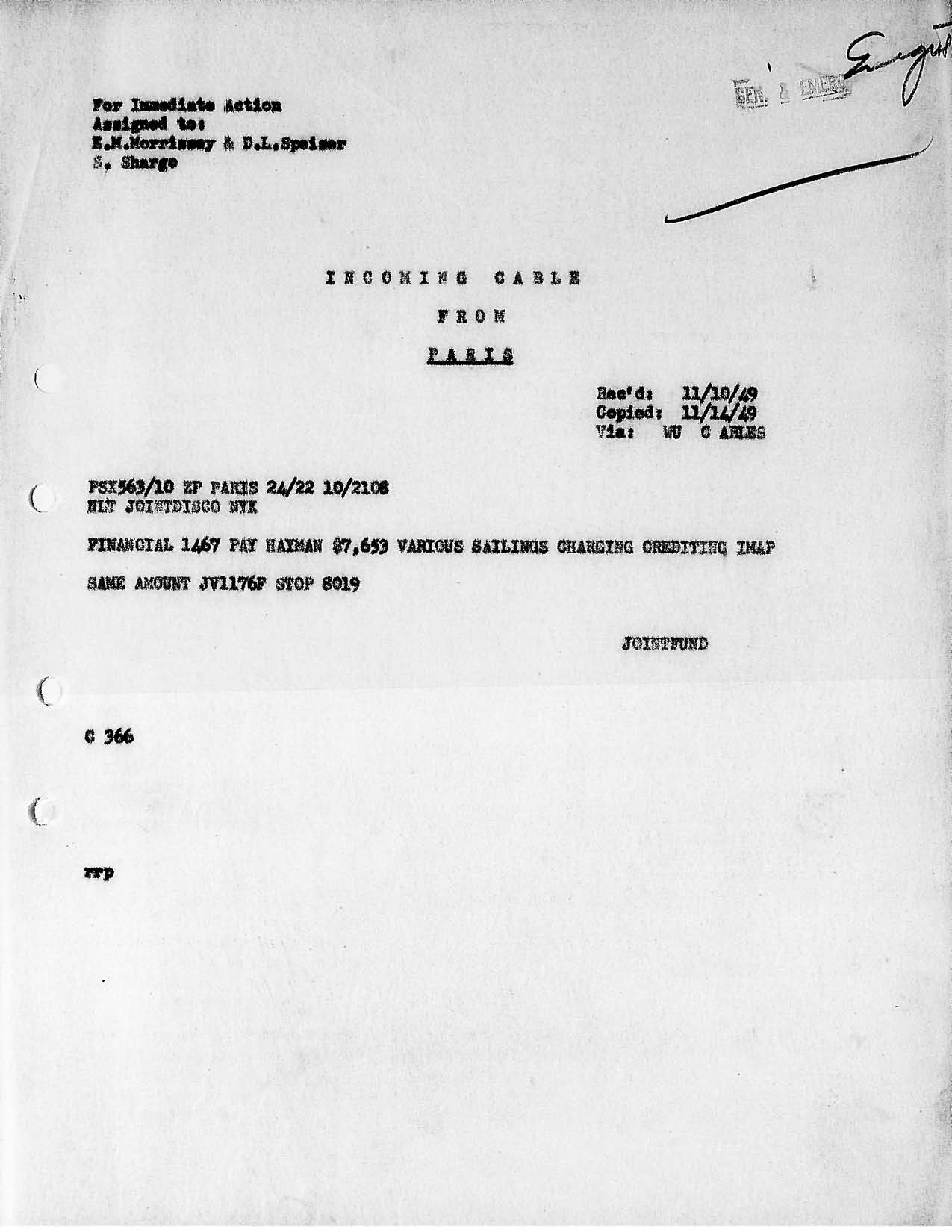

The Institute’s collection of oriental manuscripts is digitized and holds over 1,125 works (743 codices) in Arabic, Turkish, Persian and Bosnian dating from the thirteenth century to the start of the twentieth century. The manuscripts pertain to a wide array of subjects from law and politics to music and rhetoric. The earliest dated work is from 742 AH/1341-2 CE. Many of these manuscripts are especially valuable because they originated in Bosnia and were donations from the private collections of notable families. The manuscript catalog can be accessed here. In addition to this collection, one can also access facsimiles of the Oriental manuscript collection of the Goethe Institute in Frankfurt with materials from Morocco, Iraq, Egypt and other medieval Islamic cultural centers.

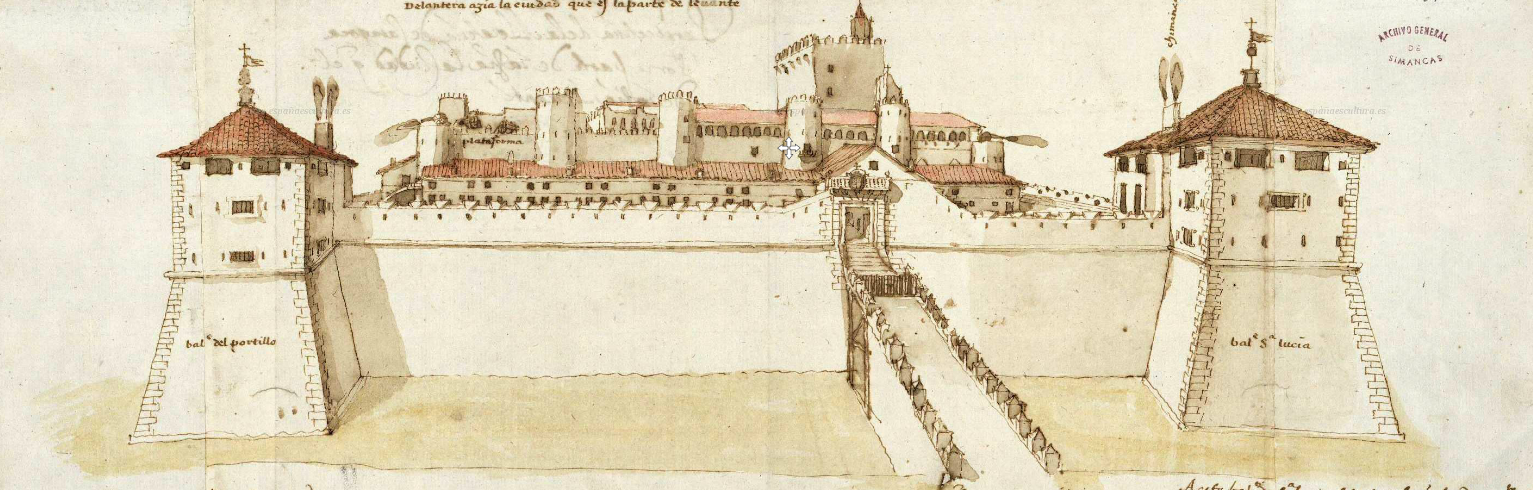

The institute’s archive holds original documents and copies from various periods relevant to this region’s history, in particular a collection of materials from the recent war in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1991-1995 (periodicals, documents, photographs, video and audio material). The cartographic collection includes maps of various themes, from the historical and topographic to the touristic and climatic, and from various centuries and points of origin in Eurasia. The collection includes about 2,000 maps, mainly of Bosnia and Herzegovina but also former Yugoslavia, Europe and the world. It may be of interest to students of art and art history that the institute also has an extensive art collection numbering 1,500 pieces and containing works by 200 Bosniak, former Yugoslavian and Austro-Hungarian artists. The collection is displayed throughout the institute (galleries in the main library building, the institute club and the former bath house (hamam) and includes paintings, graphic art, sculptures, and tapestries.

Research Experience

The library’s holdings are cataloged electronically and may be accessed via the institute’s website or at computers on-site. The catalog navigation site is in English. An additional catalog of new additions to the library as well as a catalog of Goethe University’s holdings may be found in the reading rooms. Although the library catalog may be accessed electronically, requests to view the library’s holdings are filled out by hand and submitted on-site. Order slips and submission boxes may be found at the two computers located in the lobby of the Institute. Users cannot order nor hold more than five books at one time. The five-a-day limit also applies to manuscripts even though only their digital copies may be viewed. Orders placed by 15:00 on any business day are usually ready by the start of the next day. For researchers interested in the manuscript collection, a PDF catalog of the holdings may be found on the Institute’s website or in the published edition edited by Fehim Nametak and Salih Trako. A PDF catalog of the institute’s cartographic collection is also available on its website. Because the ordering and holding limit is five items, it is recommended that you consult the catalog ahead of time, determine what is available and prioritize what you need to order. This will also expedite the process of ordering your items in person at the institute.

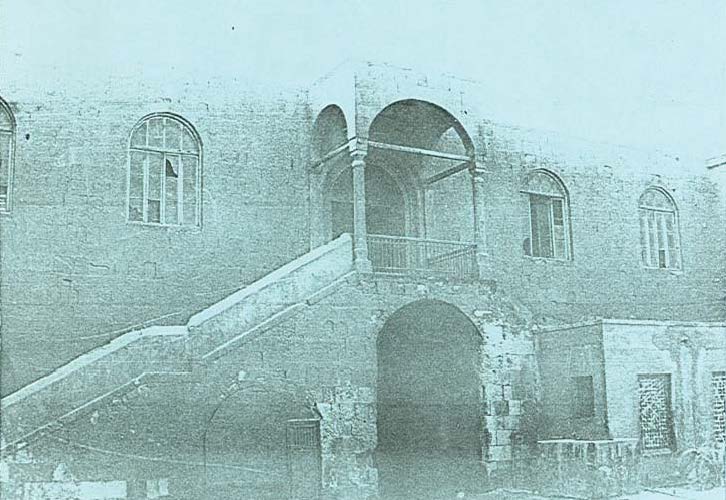

The institute’s staff is incredibly warm and friendly; it is generally a very welcoming place to work. Along with BSC (Bosnian-Serbian-Croatian), some of the staff also speaks English and tours for large groups may be arranged in various other languages. The librarians can be approached with questions about the library and the various collections as well as the process of ordering books, using the reading room, and paying for copies. Because the institute’s archive is not open to the public, if you plan to utilize it, ask the librarians to notify the correct staff who can answer your questions regarding its holdings. The reading rooms are cozy and warm with large windows and a wonderful view of the Gazi Husrev-beg bath house (hamam) and Sacred Heart Cathedral. The reading room used most often holds eight spacious desks, one of which is equipped with a computer that can be used to access the library catalog and view ordered manuscripts. If there is another researcher viewing manuscripts, you will to arrange separate times for each of you to use the computer. The entire institute is equipped with wireless internet which is available to users. Usernames and passwords can be obtained in the reading rooms. Some of the library holdings may be found shelved in this room and can be used freely. While the reading room is rarely crowded, especially in the mornings, unoccupied electrical outlets may occasionally be difficult to find later in the day.

Access

The Bosniak Institute is open to all academic researchers who work on Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bosniaks and the surrounding regions and peoples. After providing a valid identification document (I.D. card if a Bosnian national, otherwise passport) and filling out a basic information and research project information form, you will receive a membership card. Researchers present this card and their valid identification document every time upon entering the institute. The membership card is also used to obtain any book or reproduction orders. Upon returning the books ordered or paying for your reproductions, your valid identification and user card will be returned. The overall process is very painless and simple. If you take a break during your work and plan to exit the building, you must return your holdings to the front desk for safekeeping. They should not be left unattended in the reading room.

The entry is wheelchair accessible and the building has easy-access elevators. The institute is usually closed for state and religious holidays, but apart from this, there are no other long-term closures.

Institute working hours:

Monday – Friday 8:00-16:30

Library working hours:

Monday – Friday 9:00-16:00

Wednesday 9:00-19:00

Reproductions

The institute will photocopy materials (books, magazines, newspapers) produced in the year 1945 or later for you, but the maximum amount of pages is ten. Personal digital photography of any material can only be done with permission. Materials produced before 1945 cannot be photocopied and will be scanned by the institute and provided to you in electronic form on a USB drive.

Photocopies: BAM .20 (regular 8.5×11) – BAM 1.00 (varied sizes, double-sided)

Scans: BAM 2.00 per page scan (regular) – BAM 4.00 per page scan (rush delivery)

CD: BAM 1.20

DVD: BAM 1.50

(Manuscripts are charged by the page, not by the folio, as is the case in most manuscript libraries. This means that prices are actually a pricey 4 BAM or around 2 Euros a folio. You can find other versions of some, though not all, of the institute’s manuscripts holdings at the Gazi Husrev Beg Library which charges less for digital copies.)

Transportation and Food

The institute is located in the Old Town municipality of Sarajevo in the very heart of the city and is surrounded by many famous, well-preserved Ottoman architectural remnants such as the Gazi Husrev-beg medresa and mosque. The building which houses the institute is built alongside the Gazi Husrev-beg bath house (hamam) which was restored by and remains in the care of the institute. Because of its central location and placement on one of Sarajevo’s main streets, it is easy to reach via city or commercial bus (31A), tram (Line 3) or on foot from anywhere within the city limits. However, cabs are affordable for most transportation budgets and the plethora of private companies (residents will recommend private companies due to their accountability and fair practices: Crveni Taxi, Kale Taxi, Samir & Emir Taxi, Holland Co., amongst others) make its location very expedient and relatively affordable to reach.

The institute does not have a cafeteria or a café, but the entrance floor does have an automated coffee machine which produces anything from cappuccinos to tea. Numerous cafes (some with coffee-to-go, which is unusual in Bosnia), bakeries, pizzerias and restaurants surround the Institute, so researchers have their pick and will have no issues tailoring their dietary needs to their budgets. One exclusively vegetarian and vegan restaurant is within short walking distance of the institute, but most bakeries, restaurants and sandwich shops will offer meatless options. The institute is also a thirty meter walk from a large local market where researchers can find fresh fruit and vegetables, as well as other shopping.

Miscellaneous

The institute takes a holistic approach to achieving its mission of preserving, promoting and developing the study of Bosnia and Herzegovina, former Yugoslavia and the Balkans. It is simultaneously a place of research, offering a library and an archive, and a museum in its own right. It also often coordinates and hosts academic conferences, cultural events and variously-themed seminars. Information on current and upcoming events and exhibitions can be found at the front desk. The institute also publishes and co-publishes various books and periodicals, and a list of these publications may be found on its website. Lastly, it provides scholarships to university and graduate students in various fields from Bosnian universities.

The institute has its own galleries which house over 1,500 works of regional origin from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. As the posters throughout the institute boast, new gallery exhibitions are organized regularly and are open to all. As an integral part of the institute, the Gazi Husrev-beg bath house (hamam) is also used as an art gallery and for various exhibitions on the cultural heritage of Bosnia and Herzegovina and is open for visitation by researchers as well as the general public. Alongside the on-going process of digitalization, the Institute has partnered with the Elektrotehnicki Fakultet (University of Sarajevo’s College of Electrical Engineering) to begin a multimedia project of digital preservation and reconstruction of various cultural artifacts which can be accessed through the Institute’s website (see Resources and Links).

Contact information

Mula Mustafa Bašeskije 21

71000 Sarajevo

Bosna i Hercegovina

Tel: (011) 387 33 279 800

Fax: (011) 387 33 279 777

Amina Rizvanbegović Džuvić, Mr., Director

biblioteka@bosnjackiinstitut.ba

Resources and Links

Manuscript collection catalog (PDF)

Published catalog: Nametak, Fehim and Salih Trako. Katalog Arapskih, Perzijskih, Turskih i Bosanskih Rukopisa iz Zbirke Bošnjačkog Instituta. Sarajevo and Zürich: Bošnjački institute, 2003.

Cartographic collection catalog PDF:

25 September 2014

Citation Information

Sanja Kadrić, “Bosniak Institute – Foundation Adil Zulfikarpasic” HAZINE, 25 Sep 2014, https://hazine.info/bosniak-institute/