by Chris Gratien and Seçil Yılmaz

The Turkish Red Crescent (Kızılay, formerly Hilâl-i Ahmer) is a charity organization founded during the late Ottoman period on the model of the Red Cross societies. Its activities in the areas of medicine, care for prisoners of war, and other social services, particularly during the World War I period and the early years of the Turkish Republic, make the archives of this organization a vital resource for historians interested in medicine, public health, war, and charity alike during this formative period. Recently, its archives in Ankara have been made public through a searchable online catalog, opening an exciting new field of research for Ottoman and Turkish historians.

History

The Ottoman Red Crescent was founded in 1868 partly in response to the experience of the Crimean War, in which disease overshadowed battle as the main cause of death and suffering among Ottoman soldiers. It was the first Red Crescent society of its kind and one of the most important charity organizations in the Muslim world. Its role in battlefield care made it integral to late Ottoman war efforts. The Red Crescent also played a critical role in the development of the young Turkish Republic’s health institutions.

In 2006, a major overhaul of these archives was initiated to make them available to researchers. This includes a cataloging effort similar to the organization of the Ottoman State Archives (Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi), wherein each document is cataloged, described, and shortly thereafter digitized. Most of the documents pertaining to the 1868-1911 period have been cataloged and efforts continue for later periods.

Collection

The Red Crescent archives contain a variety of documents pertaining to health and health services in the Ottoman Empire and Republican Turkey. For the Ottoman period (including World War I), these documents almost exclusively concern budget and funding issues along with services pertaining to war, particularly the 1877-78 Russo-Ottoman War (93 Harbi), the Italian invasion of Libya, the Balkan Wars, and of course, the First World War. There is very little overlap between the collections of the Ottoman archives and the Red Crescent.

In addition to offering a glimpse at late Ottoman medical institutions, social historians of the Ottoman Empire will also be drawn to documentation regarding Ottoman prisoners of war, which includes letters about and by Ottoman soldiers. The Red Crescent boasts over 300,000 POW cards from all sides of the conflict containing the names and origins of prisoners, their place of capture, and sometimes other biographical or health information. The collection also contain letters and requests from prisoners of war during the conflict. In this regard, researchers of other regions such as Europe or South Asia will find these archives useful as the Red Crescent was the intermediary between the Allies and Allied prisoners held in Ottoman territories.

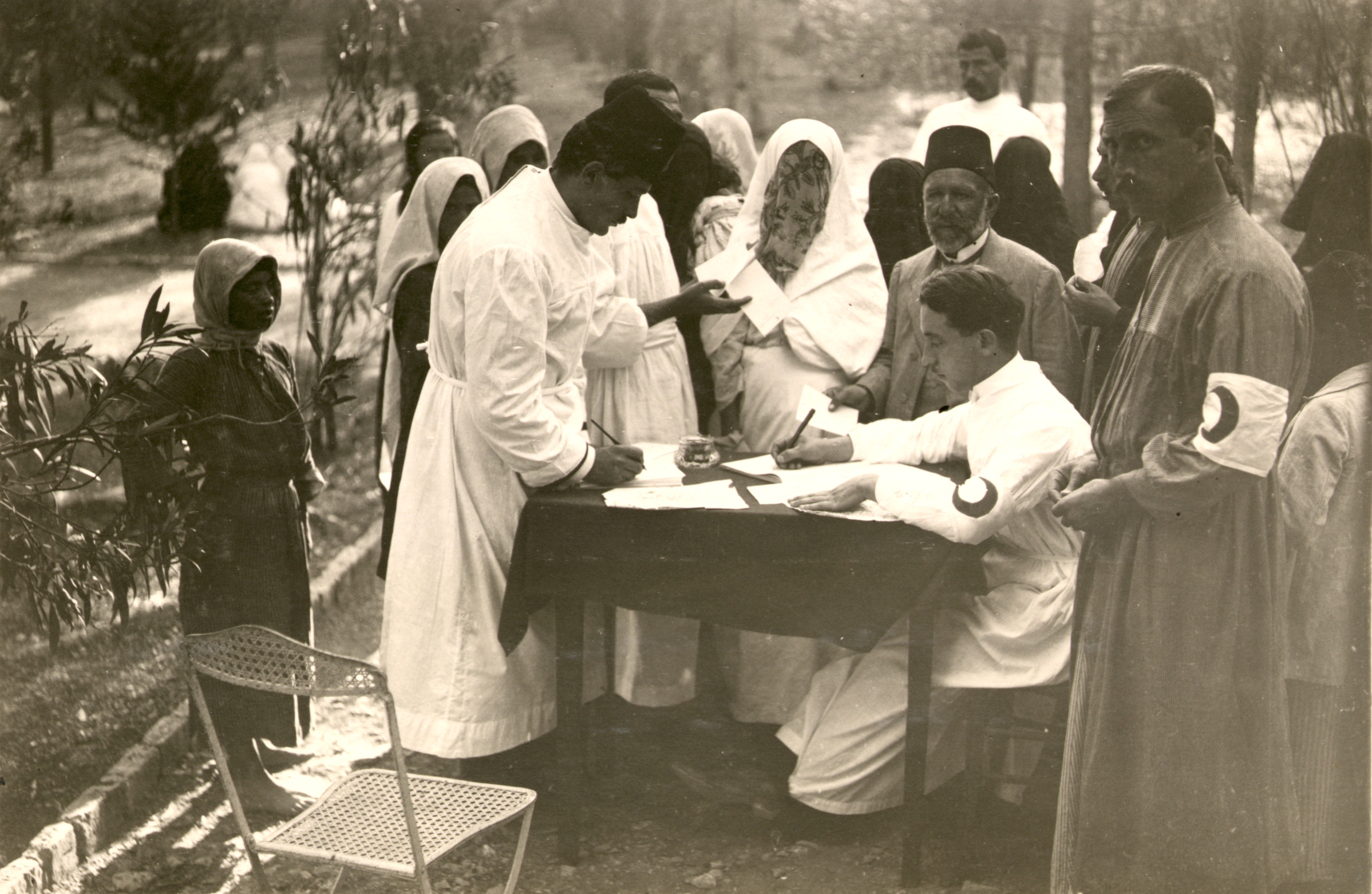

During the Republican period and even during the War of Independence, the Red Crescent took on an increasingly national character and expanded its function to issues of health in the cities and countryside. Though it has not been well-studied, the contents of the collection indicate that the Red Crescent was part and parcel of early Republican health services in rural settings, where relatively few institutions had been established by the Ottoman state. Here, there is somewhat more overlap with the collections of the Başbakanlık Republican Archives, though the Red Crescent may prove to be much richer than the former in the area of health as its catalog grows.

In addition to archival documents, there is also a decent collection of visual materials such as photographs and postcards.

The collections include several varieties of documents, including hospital reports, health statistics, personal letters, account books, and reports by health inspectors. Due to the organization of the digital catalog, researchers cannot access files or folders in their sequential order. The archive’s online search function only provides individual files with no connection to surrounding material. In order to identify documents of a particular variety or source, researchers will need to identify particular boxes of interest or the names of particular officials or organizations associated with the research topic and search using these terms (more on this below).

The contents of the Red Crescent’s collections are largely unexplored by researchers and not fully known to the organization itself. According to the archive’s website, there are some 1500 boxes and 550 bound notebooks in Ottoman and French from the period beginning with the organizations founding until the language reforms in 1928. However, it is our experience that the contents are a bit more varied than this. For example, this sample document that we have provided originates from the Egyptian Red Crescent and is entirely in Arabic.

Researchers will need a command of modern Turkish to be effective, though of course, most of the documents from the Ottoman period are in Ottoman Turkish.

The Research Experience:

For researchers, the main question regarding the Red Crescent archives is whether or not to go to the physical archives itself. The archive is located in the Etimesgut neighborhood of the Ankara suburbs, and while researchers are free to work there, there is no proper workspace. Moreover, researchers will be expected to order documents through the website and receive photocopies by mail regardless of whether they go there or not. Thus, it is possible for the entire process to be handled through correspondence. Here, we will make the argument for a visit to the archives in person and explain in which situations this is necessary.

Since this archive is relatively hard to use and access, a trip to Red Crescent Archives is probably not worth your time unless you are working on specific issues related to health, medicine, prisoners, or war, though it is always worth searching the catalog to see what might be available remotely.

There are several factors that will encourage committed scholars to make a visit arising from the limitations of the catalog. Many of the descriptions are short or obscure. Some, for example, only mention the individual who composed them, making them utterly impossible to find via keyword search unless one knows to search for that individual. Moreover, the one sentence description may prove inadequate in determining whether or not to purchase the fairly pricy photocopies (more on this below). Going to the archive in person will allow you to see entire folders (which represent the original file boxes) of the documents, which usually have a shared theme or point of origin. This also enables you to get a closer look at the actual contents of documents before ordering them and gives you access to some paper documents that have not yet been digitized. If you are already in Turkey, a visit to the archive will ultimately save you a great deal of time and money, and it will surely yield better research results.

Access

The archive is open weekdays from 9:00 to 18:00 and closes for a one-hour lunch break at noon. Researchers are asked to contact the archivists before coming, as completing the application and request process by email will expedite the research process (information here). A passport is sufficient to gain access, but bring a second form of ID to leave with the guards. Laptops are forbidden as is photography. Spoken Turkish is absolutely essential to use the archive effectively, even though some documents pertaining to foreign POWs will be in English and French. The staff is extremely friendly and helpful, and you will likely be the only researcher there on any given day. Wheelchair access may be an issue as the reading room is on the second floor.

Reproductions

The archive’s reproduction fees are relatively expensive, as revenue generated from photocopies are considered a donation to the society. Photocopies cost 50 kuruş per pose, while scans of all documents cost 10 TL per pose. The archive does not fulfill reproduction requests on site, so researchers must provide a mailing address in order to receive copies or scans. Requests are fulfilled promptly and copies are generally obtained within one or two weeks.

Transportation and Food

Although there is a neighborhood in the heart of Ankara named Kızılay, researchers will be disappointed to find the site of the Red Crescent archives is in a much more remote location in Etimesgut, a northern suburb of Ankara accessible mainly by minibus. It occupies two buildings at the back of a large site operated by the Red Crescent, so it will be normal to be a little disoriented during the first visit. There is essentially nowhere to eat near the site. There is a serviceable cafeteria used by the employees, who will likely offer you to accompany them to lunch if you are just there for a day or two. In general though, we recommend researchers pack a lunch.

Miscellaneous

The library staff will give researchers a short tour of the modest museum and library at the archives upon their visit. This museum contains some important visual materials, artifacts, and books and publications by and about the organization that may be consulted by researchers. If you are doing extensive research at the Red Crescent, particularly on the institution itself, inquire about the contents of the museum as it may contain some very interesting materials.

Future Developments

As the digitization and cataloging process is ongoing, it is always worth checking in periodically to see if anything on your topic has been added.

Contact information

Address: Arşiv Yönetimi Bölümü

Türk Kızılayı Caddesi No:6

Etimesgut – ANKARA

Archives Department Administrator

Hande UZUN KÜLCÜ

Tel: +90 (312) 293 64 26

handeu@kizilay.org.tr

Fax: +90 (312) 293 64 36

Resources and Links:

Red Crescent Archives Catalog (in Turkish)

Full PDF of Ahmet Mithat Efendi’s 1879 work on the Red Crescent’s Foundation (in Ottoman)

About the Authors

Chris Gratien is a doctoral candidate at Georgetown University

Seçil Yılmaz is a doctoral candidate at City University of New York.

Cite this: Chris Gratien and Seçil Yılmaz, “Red Crescent Archives (Turkey),” Hazine, 13 November 2013, https://hazine.info/2013/11/13/turkish-red-crescent-kizilay-archives-ankara/