Introduction

The library of the Orient-Institut Istanbul is a specialized research library dedicated to the study of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey in all its aspects (linguistics, history, literature and social sciences); and, to a lesser extent, to the Turkic peoples, languages, and literatures of Central Asia. The collection comprises currently about 48,000 monographic volumes in various languages (Turkish, German, English, Ottoman, French, Armenian, Russian etc.) and over 1,500 periodical titles. It offers access to e-books and e-journals as well as to database holdings. Readers can also access the Islamic Studies e-Book Collection by the provider Al-Manhal within the network of the institute. This collection comprises at the moment 2,035 titles, mainly in Arabic.

The Orient-Institut Istanbul is located in Cihangir, Istanbul, Turkey. Cihangir is a neighborhood in the close proximity of Taksim Square.

History

The institute and its library are an offspring of the Orient-Institut Beirut, whose researchers had to leave Lebanon in 1987 because of the civil war and found a temporary home in Istanbul. With the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the subsequent rise of interest in the Turkic world, the institute remained in Istanbul as a branch office of the Orient-Institut even after the directorate and some of its researchers were able to return to Lebanon in 1994. In 2009, the Orient-Institut Istanbul became an independent research institution. Since 2003, it has been affiliated with the Max Weber Foundation.

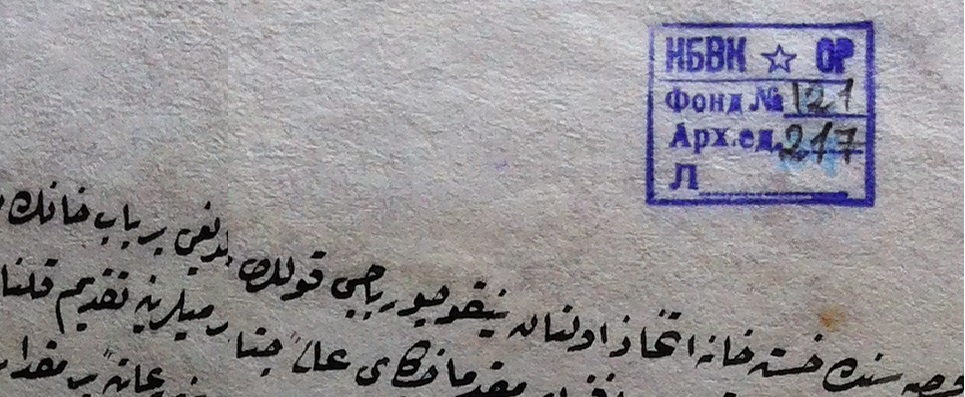

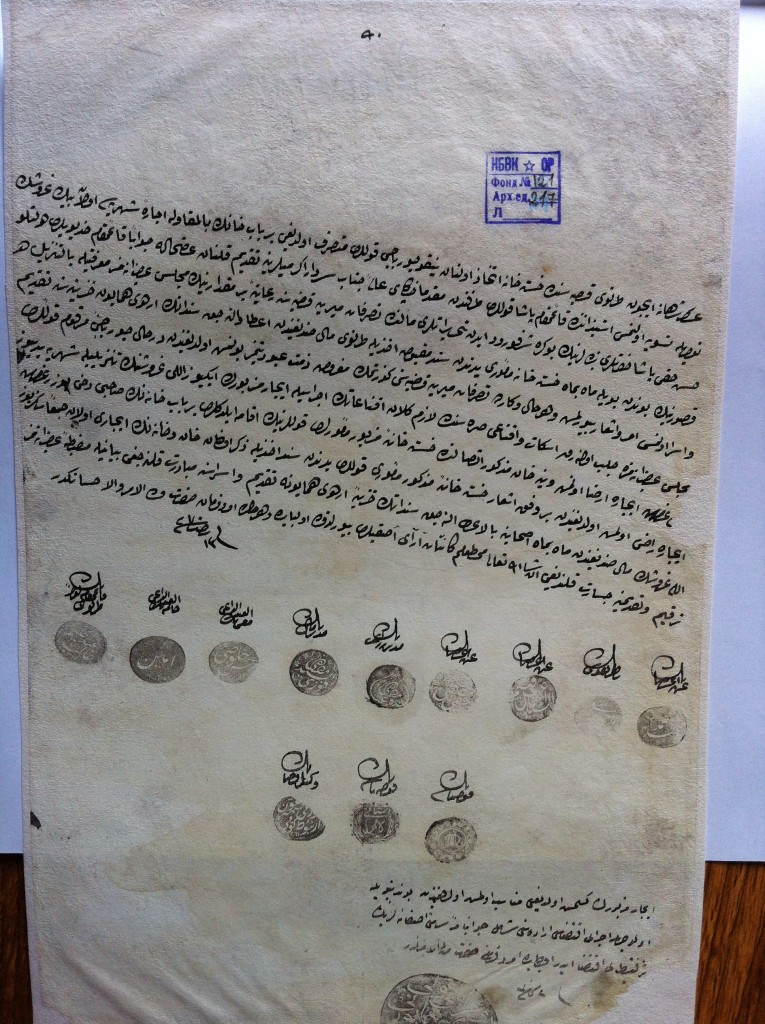

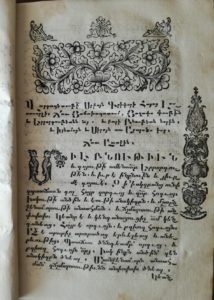

From the very beginnings, acquisitions had the objective of establishing a research library for Ottoman, Turkic, and Islamic studies in accordance with the academic profile of the institute. Its main aim has been to serve the purposes of the in-house researchers. Thus, acquisition is driven by the needs of current as well as prospective researchers, be it in the fields of history, literature, language, religion, culture, or society. This includes not only academic books and journals, but also primary source material. Accordingly, a great number of Ottoman books and journals as well as books and journals from the early Republican period have been purchased at antiquarian bookshops. In general, manuscripts are not part of the collection strategy. Since one of the objectives of the institute is the promotion of academic exchange between Germany and Turkey, relevant academic publications in German are acquired on a regular basis.

Collection

The library of the Orient-Institut Istanbul collects for the most part print material related to Turkey and the Ottoman Empire. Besides books and journals, we also collect music and documentary films on CD and DVD.

It is a highly specialized library with currently over 48,000 monographic volumes and a collection of more than 1,500 journals, 120 of them as currently running subscriptions. Our oldest monograph dates back to the 16th century.

The collection has its emphasis on the study of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey in all aspects (linguistics, history, literature and social sciences). It also includes literature concerning Turkish-speaking groups of the Ottoman Empire’s former territories, the languages of Turkey, the religions of the Ottoman Empire and “Turkish Islam.” The Turkic peoples, languages and literatures of Central Asia also fall under the purview of our collection. Publications on the history of Turkey before the time of the Seljuks are not acquired.

Besides printed material, with the establishment of the research field “Music in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey” in 2011 the library began to focus on literature on music as well as on audio material. In 2016, a collection from the late German journalist Birger Gesthuisen with more than 280 music CDs and records, especially from musicians in the North-Western European Gurbet, was donated to the library.

For the institute’s special research project on “New Religiosities in Turkey” between 2011-2017, a special collection was established that comprises currently about 2,700 volumes related to new religious movements, spirituality, superstition, occultism, esoteric belief, alternative healing methods, etc. Additionally, a comprehensive collection of journal articles and grey literature on the topic is currently being catalogued.

The Research Experience

All monographs and journals can be retrieved in our OPAC. Besides this, articles from edited volumes like conference proceedings and festschrifts available at the library are likewise retrievable.

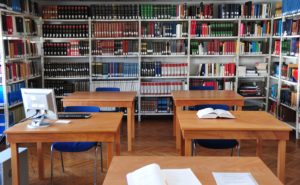

Since the collection is currently spread out over six floors in two residential buildings, books are generally grouped according to their subject. In anticipation of the institute’s relocation to a building with a separate book repository, we have started to organize the books according to the numerus currens system since January 1, 2018.

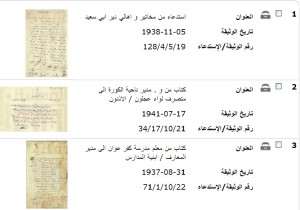

Recently, some of the most fragile materials of the library were digitized. Those digital materials are hosted by Menalib, the Middle East Virtual Library. Since only very fragile publications are digitized, access to the originals is normally not possible.

Most of the library’s material is immediately available for the researcher, but those parts of the collection housed in the second building must be ordered a day in advance. This can be done directly through the OPAC by mail request.

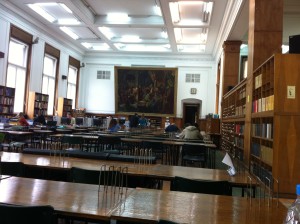

The reading room offers seven reading spaces, one with a computer for catalogue research, etc.. WLAN is available.

The librarians speak Turkish, Armenian, German, and English.

Access

The library is open to the public from Monday to Thursday from 10am to 7pm and on Friday from 9am to 1pm. We are open in summer, but closed on official Turkish holidays, as well as Easter and between Christmas and the New Year.

The library is open to everyone without prior registration. Library users are asked to enter their name in our guestbook, which serves merely statistical purposes.

Reproductions

Library users are free to take photographs or use a book scanner free of charge within the limits of the copyright regulations. The book scanner is used with one’s own USB-stick.

Photocopies are permitted in accordance with copyright regulations. Originals are sent by our staff to a nearby copy shop for next-day delivery. The copy shop currently charges 0.15 TL per copy, plus tax, (December 2018).

Transportation and Food

The institute is situated in Cihangir, within walking distance from Taksim Square.

A lot of cafes, bistros and local restaurants (lokantalar) are nearby as Cihangir is an up-and-coming neighborhood, with accordingly elevated prices. Unfortunately, we don’t have the space to allow for coffee breaks or having lunch on our premises.

Miscellaneous

The library of the Orient-Institut Istanbul is a member of BiblioPera, a network of research centers in Beyoğlu. The heart of the network is its union catalogue. For more information, please click here.

The Orient-Institut Istanbul hosts lectures and symposia and organizes conferences together with academic partner institutions. The institute has a scholarship program for doctoral candidates coming from abroad for a research stay in Istanbul up to six months. The announcement is published annually on our website, usually in late autumn.

Future Plans and Rumors

The Orient-Institut Istanbul will move from Cihangir to the Tünel district within two to three years. The new location will be close to the Şişhane Metro station on Galip Dede Street. Her şey çok daha güzel olacaktır.

Contact information

Orient-Institut Istanbul

Susam Sokak 16/8

Cihangir, 34433 Istanbul

Tel. +90-212-2936067

https://www.oiist.org/en/bibliothek/

Map of location

Resources and Links

Here you can check which online journals you have to access within the premises of the Orient-Institut Istanbul.

On the library’s website, also find a list of relevant online resources, some freely accessible some only from the network of the institute.

Keyword Tags

Istanbul; Turkey; Early Modern; Modern; Printed; journals, newspapers; music

Biography

Dr. Astrid Menz is the head librarian of the library of the Orient-Institut Istanbul.

ORCID-ID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1741-3250