Written by Secil Uluışık

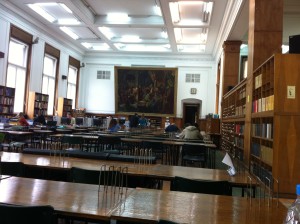

St. Cyril and Methodius National Library of Bulgaria (Natsionalna Biblioteka Sv Sv Kiril i Metodiy, hereafter, NBKM), located in Sofia, has one of the richest Ottoman archives with respect to the quantity and variety of materials. Founded in 1878, the NBKM’s holdings were significantly expanded in 1931 with the acquisition of millions of Ottoman documents from Turkey. Today, the NBKM’s Oriental Department Collection (Kolektsiya na Orientalski Otdel) contains more than 160 sijills, 1000 defters and registers, 1,000,000 individual documents, and countless registers of religious endowments (waqf/awqāf) from all provinces of the Ottoman Empire between the fifteenth and the twentieth centuries. In addition, it has a valuable Persian, Arabic, and Turkish manuscript collection. Apart from its Oriental Department, the Bulgarian Historical Archive (Bŭlgarski istoricheski arkhiv) houses materials dating mostly from the nineteenth century and written in both Ottoman Turkish and Bulgarian. In this sense, NBKM is a hidden gem for scholars of the Middle East and the Balkans.

History

The NBKM was first established in 1878 as the Sofia Public Library but quickly became the National Library in 1879. During 1870s and 1880s, NBKM officials collected various Ottoman materials from local waqfs and libraries throughout Bulgaria, and brought them to the Oriental Department of the NBKM. In 1944, the entire building was destroyed in the course of the war. While some materials were irreparably damaged during the attacks, much was saved. These surviving materials were transferred to local libraries in order to be protected from further destruction. All the transferred materials were eventually brought back to the NBKM’s main building in late 1940s. The NBKM’s current building was officially opened in 1953. The NBKM gets its name from St. Cyril and St. Methodius, the eponymous brothers who invented the Cyrillic alphabet in late ninth century. A monument of the two brothers holding the Cyrillic alphabet in their hands stands tall in front of the NBKM, and it is also one of the landmarks of the city.

In 1931, as a part of its political agenda based on the rejection of the Ottoman past, the Turkish government sold a massive amount of Ottoman archival documents to a paper factory in Bulgaria to be as used as recycled waste paper. This event became known as the “vagonlar olayı” (the railcar incident) because the documents were transported in train cars and when the events were publicized in Turkey they triggered a heated debate among scholars and politicians of the time. Once Bulgarian customs officials realized the materials were actually Ottoman state documents and not waste, the papers were deposited in the NBKM. Today, these documents constitute more than 70% of the entire Oriental Department of the NBKM, which continues its tireless effort to catalog and preserve them.

Collections

The NBKМ has eleven collections varying from Slavonic and Foreign Language Manuscripts, to the Collection of Oriental Department. Information about each collection and the structure of the collections can be found here.

The Collection of Oriental Department has two main archives: the Ottoman Archives and the Oriental Manuscript Collection. The Bulgarian Historical Archive is also located in Oriental Department since it includes many documents in Ottoman and Bulgarian. The following are collections that might be of direct interest to historians of the Middle East:

Sijill Collection:

A sijill is an incoming-outgoing register, organized by the qadi (judge) or his deputy in a specific settlement. A sijill also includes copies of documents, written by the qadi. There are more than 190 sijills in this collection from the sixteenth to the late nineteenth centuries. They are catalogued based on their region such as Sofia, Ruse, Vidin etc. The sijills from Sofia and Vidin have call marks beginning with “S”, while sijills from Ruse, Silistra, and Dobrich have call marks beginning with “R”. Most of the sijills have card catalog entries in Turkish in either Latin or Ottoman script. The earliest sijill is from Sofia dated 1550, whereas vast majority of the sijills are from the eighteenth century. Most of them are from Vidin (71 defters), and then Sofia (59 defters.). Much of the sijill collection has been digitized and can be accessed through the official website of the NBKM.

Waqf Registers:

There are more than 470 separate waqf (endowment) registers from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries in this collection. In addition, some other waqf registers can be found inside the sjill collection. Registers and series of waqf documents are compiled in the form of deste (separate register bunches) and waqf sijills. They are written primarily in Ottoman, while several of them are in Arabic. The earliest waqf register dates back to 1455; and the latest to 1886.

A comprehensive inventory of the waqf registers can be accessed here.

Miscellaneous Funds:

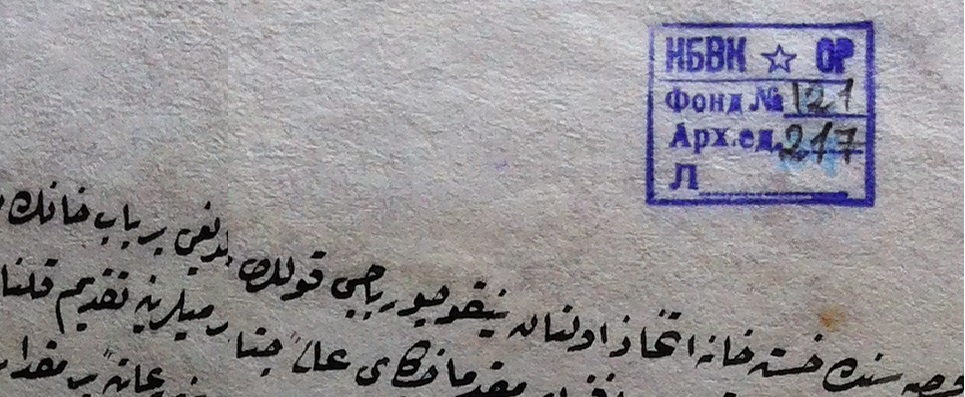

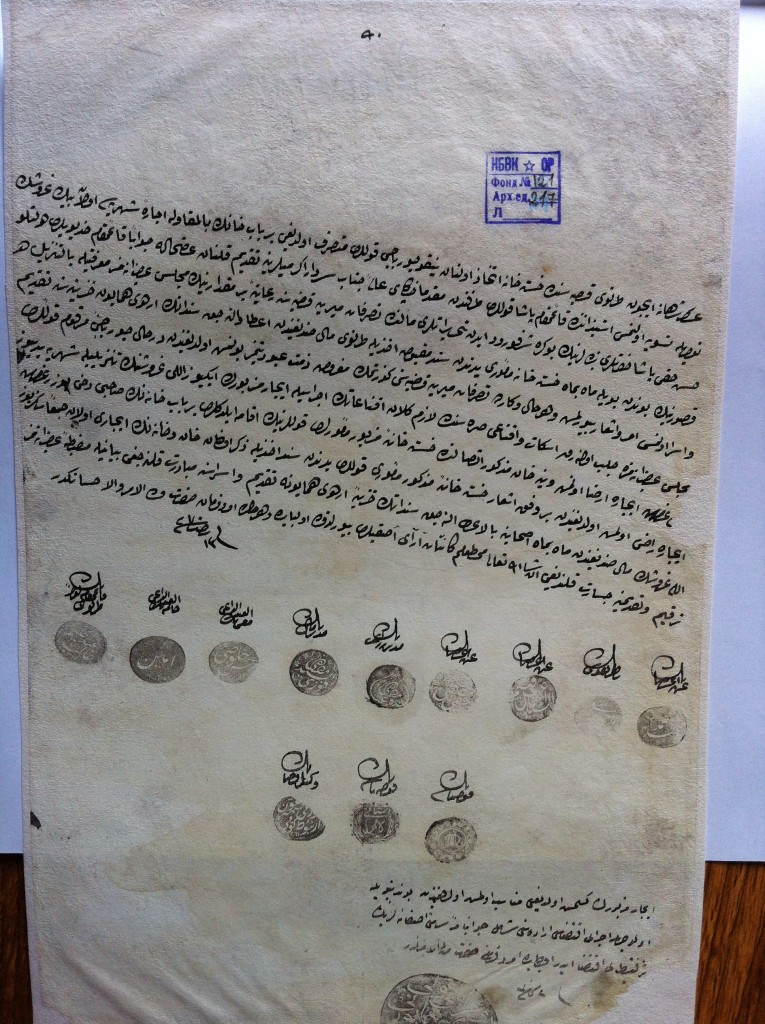

This collection includes the rest of the Ottoman documents in the Oriental Department. Many cadastral surveys (timar, zeamet and icmal defters) can be found in this collection. There are also various other types of registers and financial account books (ruznamces) here. In addition, all individual documents such as fermans, buyruldus, arzuhals, ilams and various individual correspondences and materials are located in these funds.

Most of these Ottoman materials in this collection are cataloged according to the region they are related to, and each region has a separate fund with a different number. For instance, documents related to Istanbul are cataloged as F1, Damascus as F 283, Iran as F 295, Hijaz as F283, Albania as F212, Austria as F290, Smyrna as F238, Skopje as F129, Malatya as F249 and so on. Most of the funds have sub-collections and they are cataloged separately. Most of the entries in fund numbers have dates, and some of them include keywords such as “military”, “church”, “taxation”, “timar” giving some basic clues about the type of the document. Unfortunately, there is no other information available to the researcher about the documents from the catalog. However, there are some publications, mostly written by the staff of the Oriental Department, such as inventories and catalogs of selected funds of Ottoman documents, which are helpful. So, it is vital to consult these published volumes, which are mostly in Bulgarian. All catalogs in this collection are also in Bulgarian and handwritten. The number of the documents in this collection exceeds 1,000,000 and none of them have been digitized. Their dates range from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries.

Oriental Manuscript Collection:

This collection has about 3,800 volumes in Arabic, Turkish and Persian. Around 3,200 of these volumes are in Arabic, 450 are in Turkish and 150 are in Persian. The earliest manuscript is an eleventh-century copy of the hadith collection of al-Jami’ al-Sahih of Muhammad al-Bukhari (810-870). One of the most valuable manuscripts of this collection is a sixteenth-century copy of the work of the twelfth-century Arab geographer Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Idrisi, Nuzhat al-mushtaq fi ikhtiraq al-afaq (Book for Entertainment of the One, Longing to Cross the Countries Wide and Far). Partial catalogs in English, Arabic, and Bulgarian exist for this collection and are available in the reading room.

Newspaper Collection:

This collection is located in Bulgarian Historical Archive section of the Oriental Department, and it includes the newspapers published between 1844 and the 1940s. The majority of the newspapers are in Bulgarian, but those published until the late 1870s are both in Ottoman and Bulgarian. The catalog of this collection is a reference volume written in Bulgarian that can be found at the reading room at the Oriental Department. Since 2014, the majority of materials in this collection have been digitized and now are available for researchers. Digitization efforts continue, so researchers should check the online catalogue research tool on a regular basis.

The Research Experience

Researchers should note that all administrative materials at the NBKM, including the catalogs and all paperwork needed for registration, reproduction of documents etc., are in Bulgarian. Likewise, all catalogs in the Oriental Department are also in handwritten Bulgarian. The cataloging system does not have a regularized format for the Oriental Department. Some of the catalog entries have Ottoman explanations in addition to Bulgarian, but they are very few in number. Most of the Ottoman materials are cataloged according to the region, and each region has a separate fond letter with a different number. Specific collections have their own cataloguing system as explained in previous section.

Materials can be requested from Monday to Friday between 9:00 and 15:30, and will be available the next day. All staff members, both in the Oriental Department and in other sections of the library, are very helpful and supportive. The researcher should keep in mind that documents from a specific section needs to be requested in that section. However, for reproductions, the researcher must obtain approval of both the director of the Oriental Department and the general secretary of the Director of the NBKM. While this seems burdensome at first, it is a relatively comfortable process as all staff members try to help foreign researchers.

Access

There are two requirements to gain access to the Oriental Department. First, the researcher needs to fill out an application form to gain access to the NBKM. A passport, visa and a photo are needed for this process. As visa requirements vary by nationality, the researcher should consult the local Bulgarian embassy regarding the required documents. (North American citizens can stay in Bulgaria without a visa up to three months. Turkish citizens, and citizens of any country who are required to obtain a visa to enter the EU, however, must obtain a visa at their local consulate. I obtained a student visa as a Turkish citizen and fellow of American Research Center in Sofia, but a Schengen visa might be accepted to conduct research for shorter periods.)

This registration process takes around thirty minutes. Once registration is completed, the researcher receives an ID card, which must be shown every time she enters the NBKM. There are three, six or twelve-month registration options; the fee for three months is $18 while the rest costs $20, regardless of the duration. Researchers can access all departments with the issued ID card.

To access the documents in Oriental Department researchers must fill out another form that needs to be submitted to the director of the department. In addition to the form, graduate student researchers are asked to bring a letter from their supervisor explaining their aim, current affiliation, and academic status. The director, Stoyanka Kenderova, is very helpful and supportive. For foreign researchers, contacting her might be the only way to gain some guidance in the research process as she speaks Turkish, Arabic, French, and English. It must be noted that most of the staff working at NBKM in general, and the Oriental Department, in particular, do not speak English. As such, some knowledge of spoken Bulgarian or the friendship of a Bulgarian-speaking fellow researcher is definitely helpful when communicating with the staff.

The NBKM is open to researchers from Monday to Saturday, between 8:30-19:00 except on official holidays. The Oriental Department’s working hours are Monday to Friday, 9:00-18:00, and on Saturdays, 9:00-15:00. It is closed every August, and also every last Tuesday of the month for cleaning, and housekeeping purposes. All sections are wheelchair accessible, except for the cafeteria.

Reproductions and Costs

To request reproductions, researchers must fill out a form that needs to be approved by the General Secretary of the NBKM and the director of the Oriental Department. Copies of materials can be obtained either as a photocopy or digital photos. Researchers can also take their own photos. In all cases, the cost for a photocopy or photograph of a regular size document is 3 Bulgarian Leva ($2/ page.) The cost for a single page of illustrated or larger materials ranges from 4.5 to 6 Bulgarian Leva ($3 to $3.5)

Transportation and food

The NBKM is located in the heart of the city on Vasil Levski Blvd next to the Sv. Kliment Ohridski University of Sofia, and across from the Alexandr Nevski Square. Almost all city buses pass through the bus stop in front of the National Library. Lines 2 and 4 are the most frequent. Tickets for buses can be purchased at small kiosks at the corners of the intersection of major streets or on the bus. One can also take the metro since metro station is a three to four minute walk from the library. If you are staying at the city center or surrounding neighborhoods such as Hadji Dimitar, where the American Research Center in Sofia (ARCS) is located, or Vitosha Street, where many of the social events take place, it takes fifteen to twenty minutes to walk to the NBKM. A Metro or bus ticket costs 1 Leva (75 cents).

A variety of food options are available around the NBKM. The library also has its own cafeteria, which is a good option for a quick coffee, water, or snacks in cold weather. Yet it is not preferred by most researchers as there are better options available close by the library. There is also a small kiosk right next to the NBKM building selling snacks, pizza, sandwiches, and coffee throughout the day. Just across from the kiosk, there is a popular restaurant-café, Modera Café, which is usually preferred by Sofia University students and staff. There are also many various options for breakfast, lunch and dinner in small streets around the University and NBKM. Depending on your preference, a lunch can cost between $2 and $10 at these locations. You can also bring your own lunch and eat it at the outdoor garden of NBKM. However, it should be kept in mind the garden becomes crowded and finding a spot can be difficult, especially in nice weather.

Contact Information

Address: Sofia 1037, 88 Vasil Levski Blvd

Tel.: (+359 2) 9183 /101

Fax: (+359 2) 843 54 95

Director of the Oriental Department: Stoyanka Kenderova

Assistant of the Director of Oriental Department: Milena Zvancharova

Resources and Links

Further Readings

Binark, İsmet. Bulgaristan’daki Osmanlı Evrakı. Ankara: TC Başbakanlık Daire Müdürlüğü.1994.

Dobreva, Margarita. “Aya Kiril ve Metodiy Milli Kütüphanesine Bağlı Oryantal Bölümü’ndeki “Vidin” Ön Fonu Defterleri”. Osmanlı Coğrafyası Kültürel Arşiv Mirasının Yönetimi ve Tapu Arşivlerinin Rolü Uluslararası Kongresi Bildirileri 1. Ankara: TC Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı Tapu ve Kdastro Müdürlüğü Arşiv Daire Başkanlığı Yayınları. 2013, 183-223.

Kenderova, Stoyanka. “Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts in SS Cyril and Methodius National Library, Sofia, Bulgaria” Hadith Sciences. Ed. by M. Isa Waley. London. 1995.

Özkaya, Yücel. “Sofya’da Milli Kütüphane Nationale Biblioteque’deki Şeriyye Sicilleri” Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi (Ankara), c. XIII, № 24, 1980, s. 21–29.

Гълъб Гълъбов, Бистра Цветкова. Турски извори за историята на правото в българските земи. Състав.T Т. 1-2. София. 1962- 1971.

Ivanova, S. “The Sicills of the Ottoman Kadis: Observations over the sicill collections at the National Library in Sofia”. Bulgaria. Studies in Memoriam Prof. Nejat Göyünç. Ed. K. Çiçek. Ankara, 2001

***

I would like to thank Margarita Koleva Dobreva, Stoyanka Kendarova, Rossitsa Gradeva, and Milena Zvancharova for their valuable help and guidance at the archive. I benefited from works cited below.

***

Cite this: Seçil Uluışık, “National Library of Bulgaria,” HAZINE, 9 May 2015, https://hazine.info/national-library-bulgaria/

Secil Uluisik is a PhD candidate in History Department at the University of Arizona. She works on provincial governance, politics of taxation, and networks of local power holders during the late eighteenth early nineteenth century in the Ottoman Empire.