The last ten years alone have seen a boom in digital resources for Islamicists and historians of the Middle East. Be it bibliographical tools, like Jara’id, or online photo archives, like Akkasah, the future will only continue to see the expansion of our toolkits, inspiring new research questions in the process. One such tool is the Islamic Painted Page (IPP). In honor of the site’s relaunch this month, we have an interview with its creator, Stephen Serpell.

Jesuit Archives & Research Center, Saint Louis (MO)

Recent developments across the Middle East have made archival retrieval difficult to say the least. Iraq is no exception. In fact, there are many intricacies and obstacles related to the writing of Iraqi history, whether, cultural, social or economic. In the wake of the 2003 invasion, looting and vandalism left libraries, archives, museums, and government buildings in ruins, most notably in the examples of the Ba’th archives, now at the Hoover Institution, and the ISIS Files. The loss of these sources, the toll of dictatorship, years of sanctions, and the present state of violence in Iraq pose serious challenges to critical studies of Iraq. As a result, perhaps, twentieth-century Iraqi history has until recently been written through a rather narrow use of British colonial sources located in the National Archives in London. The collections of the Jesuit Archives & Research Center (JARC) are a welcome exception that proves the importance of thinking about Iraqi and Middle Eastern archives transnationally. The collection, it must be said from the outset, is most directly relevant to scholars interested in twentieth-century Iraqi history. It contains the materials of the Jesuit Mission in Iraq as well as correspondence with the Jesuit community in the US and covers the period from 1932-1969. However, those working on missionary history, US-Iraqi relations, elites, education, sport, and masculinity in the Middle East will also find the collections useful.

History

JARC is the home of the archives of the US Jesuit provinces and the missions they administered abroad. The New England Province administered the Jesuit mission in Iraq, which makes this archive the only one in the collection directly related to Middle Eastern history. In November 2017, the archives of the thirteen Jesuit provinces were centralized and relocated to a brand new facility in Saint Louis.

The Jesuits established an elite high school for boys (Baghdad College) in 1932 and a co-educational university (al-Hikma) in 1956 in Baghdad. However, already in 1921, the Chaldean Patriarch in Iraq, Mar Emmanuel II Thomas, a graduate of Université Saint-Joseph in Beirut, sent a petition to Pope Pius XI in Rome asking for the establishment of Christian secondary education in Baghdad. More than a decade passed, however, before the desire for Christian secondary education in Iraq materialized. Georgetown professor and founder of its School of Foreign Service, Fr. Edmund A. Walsh, S.J., arrived in Baghdad in 1931. Walsh had been sent to Baghdad in his capacity as fundraiser and officer of the Vatican-sponsored Catholic Near East Welfare Association. In Iraq, Walsh met with Iraqi government officials to discuss the possibility of opening a Jesuit high school in Baghdad. In March 1932, Walsh received a cable from the Iraqi Ministry of Education giving him the green light and the school officially opened in September of that year. While the Vatican was influential during the founding of Baghdad College, it quickly became an American Jesuit project. The Jesuit mission in Iraq was administered by the New England Province and funded by the presidents of eight American Jesuits colleges and universities: Boston College, the University of Detroit, Fordham University, Georgetown University, Loyola University in Chicago, University, Loyola University in New Orleans, St, Louis University, and the University of San Francisco. Together, these eight institution formed the The Iraq-American Educational Association. Between 1932-1969, the Jesuits in Iraq educated several generations of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Iraqis, Middle Easterners, and expats from prominent families, including the sons of ministers, Prime Ministers, senior government officials, ambassadors, consuls, businessmen, and newspaper editors. In 1969, the Jesuits were expelled from Iraq and Baghdad College and al-Hikma were “Iraqicized.” In the 1970s, al-Hikma was turned into a trade school. Equipment and the library were taken over by the University of Baghdad and most of the documents were moved to the US. BC continued as a college preparatory school, its teaching staff now coming from the University of Baghdad. The Jesuit church and cemetery were taken over by the Chaldean Patriarch and turned into an orphanage.

Collection

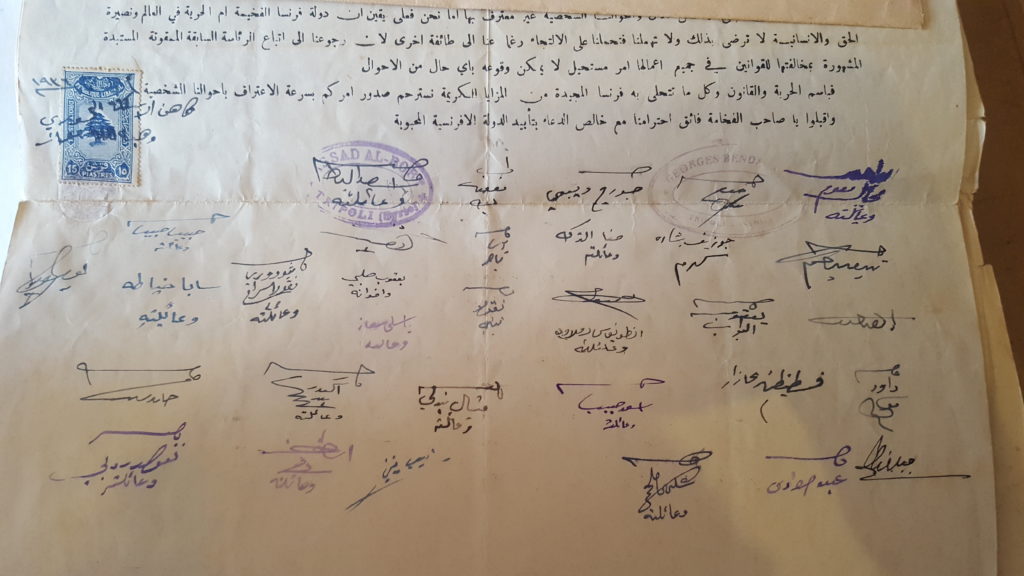

The collection is extremely well-organized and the finding aids, which can be downloaded online here, are very detailed. The collection is the home of a large body of documents pertaining to the education of several generations of mostly upper and upper middle class Iraqis and other Middle Easterners of all faiths at the two Jesuit institutions in Baghdad – Baghdad College and al-Hikma University. Al-Iraqi and Al-Hikma, the bilingual yearbooks of the two institutions, are very rich historical sources and perhaps the most interesting part of the collection. The yearbooks contain a wealth of information about the many clubs, societies, and extracurricular activities, such as sport and school trips organized by the two institutions. In addition, the many essays, short stories, and poems published in the yearbooks offers an opportunity to examine the expectations, hopes, anxieties, and concerns of the institutions’ students at a time when Iraq was experiencing tremendous political and historical upheaval. Finally, the yearbooks contain a wealth of photographs and several pages of advertisements for local and international businesses and products. The Baghdad College and the al-Hikma University yearbooks have been digitized and can be found here and here. Physical copies are available at JARC.

(Photo Credit: Pelle Valentin Olsen; JARC Collections)

The collection also contains the English-language newsletters of the school, al-Baghdadi, which was written to a Jesuit audience in the US. In addition, JARC is the home of alumni and school reunion materials, architectural plans and drawings, budgets, financial reports, contemporary newspaper and magazine articles about the mission, student statistics, commencement programs, promotional materials, house diaries for the boarding section, official correspondence, library catalogues, textbooks, and several other categories of documents. JARC also houses a large collection of photographs, audiovisual material, and the private papers of many of the Jesuits who taught in Baghdad. A handful of items in the collection, such as grades and report cards, are restricted. The entire collection consists of more than 100 boxes with several folders in each book.

While the collection is limited to Jesuit activity in Iraq, several documents touch upon local, regional, and international politics and developments. Researchers interested in the Jesuit mission might also find the archives of the The Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia useful. The Presbyterians arrived in Iraq in the early twenties and operated several schools, including the Baghdad High School for Girls. The Presbyterians were also active in other parts of the region.

The Research Experience

JARC is a very pleasant place to work. The building and the facilities are brand new. In fact, JARC has only been open to the public for about a year. The reading room gets a lot of natural sunlight, has large desks, comfortable chairs, lamps, several outlets, and free Wi-Fi. Gloves are provided for researchers interested in the photographic elements of the collection. More importantly, the staff is extremely knowledgeable, friendly, and helpful. Digital microfilm machines are available, but not necessary for the Iraq-related materials as none of this is on microfilm. It is possible that JARC will get more visitors when the word gets out. However, when I visited (September 2018), I was the only researcher working in the archives for more than a week.

Access

(Photo Credit: Pelle Valentin Olsen; JARC Collections)

Compared to archives in the Middle East, the archives at JARC are very accessible to researchers who have access to the United States and can afford travel. JARC is located in Saint Louis’ Central West End right next to the campus of Saint Louis University. For researchers arriving in car, parking is available for free in a private lot behind the main building. The parking lot as well as the two main entrances are handicapped accessible and the building is equipped with an elevator and ramp. The archives are open to researchers from Monday through Friday during the hours of 9:00 am to 11:45am and 1:00pm to 4:00pm. Research can be conducted by appointment only. To schedule a research appointment fill out the online Archives Request Form or contact JARC by phone or email. The staff is very prompt at responding. Upon arrival, researchers are asked to fill in and sign a form about their research topic and contact details. JARC provides 10 free photocopies. After that, a small fee is added. Staff will allow you to request several boxes at the same time. Researchers are welcome to bring phones, cameras, and laptops into the reading room. There’s no fee for using phones or cameras.

Transportation and Food

As already mentioned, JARC closes for an hour-long lunch break every day. Luckily, there are a couple of restaurants and a CVS close by. This is convenient since water and food is not allowed in the reading room. Backpacks and water bottles, however, can be stored in the lockers, which are provided free of charge. There are restrooms and water fountains at the entrance to the reading room. There’s a nice café (Café Ventana), popular with Saint Louis University students, located directly across the street from the archives. They also serve food and pastries. More cafés, restaurants, and bars can be found by walking either West or East on Lindell Blvd or Forest Park Ave. JARC is close to public transportation, which makes it possible to have lunch elsewhere in the city. Since the archives closes relatively early, researches have a unique opportunity to take advantage of the countless things Saint Louis has to offer (after they have organized their findings and typed up their notes): live music, great parks, a free zoo and botanical gardens, museums, restaurants, and bars. The hotels in Central West End are rather expensive – especially for researchers on a graduate student budget, and it might therefore be necessary to find accommodation elsewhere in the city or try airbnb, which lists several apartments close to JARC for around $50 a night.

Contact Information

Jesuit Archives & Research Center

3920 West Pine Boulevard

Saint Louis, MO 63108

United States

Telephone: 314 376 2440

Email: archives@jesuits.org

Director: jarcDirector@jesuits.org

Reference Services: jarcReference@jesuits.org

Collection Management: jarcCollections@jesuits.org

Receptionist: jarcReceptionist@jesuits.org

(Note the images of JARC are sourced from the Jesuit Archives & Research Center (JARC).Credit belongs to JARC)

Resources and Links

Saint Louis Public Transportation

Pelle Valentin Olsen is a graduate student at University of Chicago’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations. He works on modern Iraqi cultural and social history and literature.

Blogs You Should Be Adding to Your Bookmarks

By N.A. Mansour

We recently tweeted out some of our favorite blogs to follow: we threw out a couple of names you probably know and some you might not have had the chance to follow. Then our followers (and some of the people we tagged) tweeted back at us some of their favorites (particular shout-outs to Rich Heffron, Hind Makki and M Lynx Qualey). Here it is, in list form, if you don’t follow us on Twitter. Please either comment bellow on your favorites, tweet at us, or email us at hazineblog@gmail.com and we’ll update the list as we go along!

(Updated October 2019)

Continue reading “Blogs You Should Be Adding to Your Bookmarks”

An Informal Guide to Fuat Sezgin’s Geschichte Des Arabischens Schriftums

How you can use Sezgin’s GAS to improve your German, learn about your field, and find Arabic manuscripts.

So you want to learn German. Or more likely, you are required to learn German for your degree in Near Eastern Studies, Middle Eastern History, or Islamic Studies. If your graduate program is like mine, you might not receive course credit for taking German courses so you are largely left to acquire reading comprehension on your own. For those of you in this situation, I have put together a strategy for gaining German reading competency that is targeted for students in our field, especially for those focused on early and medieval Islamic history and thought. This strategy is hardly foolproof; rather, it is the result of the numerous mistakes I have made while studying German in graduate school…mistakes that I hope you can benefit from.

There is a long-standing joke in Near Eastern Studies that “German is the most important Semitic language” due to the numerous field-defining contributions of scholars writing in German (h/t to @shahanshah). While many of these works have been translated into English or French or Arabic, an abundance of German scholarly literature in Near Eastern Studies, especially articles, exists only in die Muttersprache. Speaking from experience, there’s a good chance that just when you think you have accounted for the significant secondary literature concerning your dissertation topic, you will stumble upon an exhaustively researched tome in German on your topic that you cannot afford to ignore. And if you do ignore it, you can count on one of your dissertation committee members to reference it during your proposal. But enough with the fear mongering.

•••

If you want, or need, to gain reading competency in German, an effective and edifying way to go about it is by utilizing Fuat Sezgin’s Geschichte des Arabischen Schrifttums (GAS), an invaluable bio-bibliographical survey of Arabic literature up to the mid-fifth/- eleventh century. Why Sezgin’s GAS and not Carl Brockelmann’s Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur (GAL)? Well, Sezgin’s survey is both more current and comprehensive for classical Arabic literature, and it is much less cumbersome to use than Brockelmann. Heck, the Middle East Librarians Association published a guide to Brockelmann’s GALin 1974 because the work’s organization and constant abbreviations were so obtuse to the uninitiated. If your research is focused on the post- classical period (i.e. after 360/1050), however, you may want to use Brockelmann’s GAL rather than Sezgin’s GAS for the proposed learning method below. In 2016, Brill published an English translation of Brockelmann’s GAL, which is useful but it won’t improve your German.

Do note that If you have no prior experience with German, I recommend spending a few weeks learning grammar basics and building your vocabulary (e.g. complete the first seven chapters of Wilson’s grammar) before employing Sezgin’s GAS in your German study routine.[MOU1]

So without further ado, here is my method:

Begin by getting your hands on the volume of Sezgin’s GAS that is most applicable to your area of focus. For instance, if your research focuses on hadith then check out Volume 1, which covers the fields of Quranic Studies, hadith, history, jurisprudence, theology (dogma), and mysticism. Brill published the first nine volumes of GAS while the rest, volumes ten through seventeen, are available from the Institut für Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wissenschaften.

Once you have acquired the appropriate GAS volume, grab your preferred dictionary and reading grammar and go to the section that concerns your area of focus. As for reading grammars in English, I recommend either April Wilson’s German Quickly or Karl Sandberg and John Wendel’s German for Reading, both of which are commonly used by instructors teaching German reading comprehension. I am partial to April Wilson’s grammar as it is the product of her decades of experience preparing University of Chicago graduate students for the German reading exam.

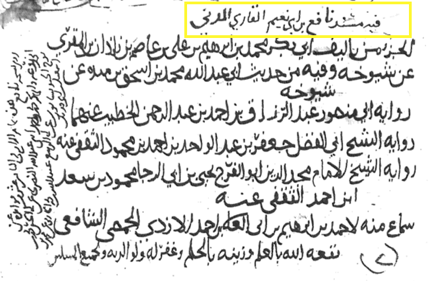

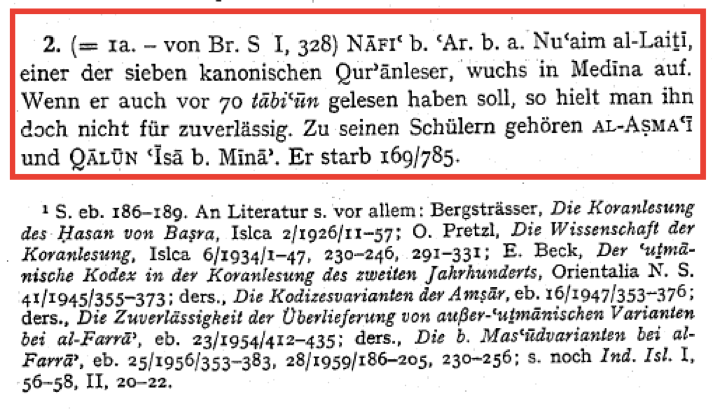

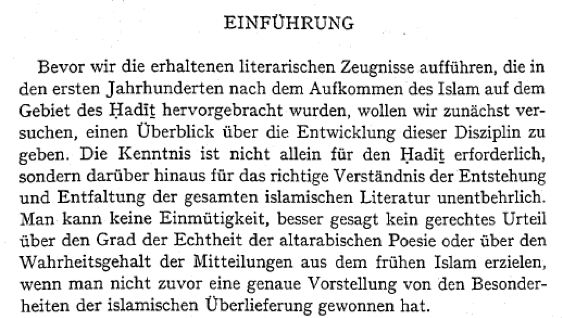

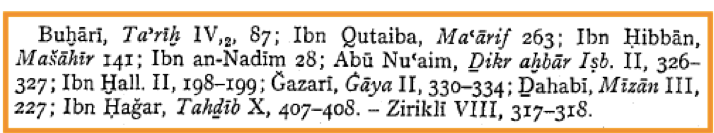

With your dictionary and grammar handy but closed—for the time being—begin reading through Sezgin’s chronologically-arranged biographies of the scholars who composed works in Arabic, both extant and lost, in your field of study. For now, just focus on reading Sezgin’s biographies, ignoring his bibliographical notes below the biographical entry. The biographies will provide you with fundamental information about the author’s life as well as the prime vocabulary necessary to read academic literature in Islamic Studies. For example, here is the biography (outlined in red) of Nāfiʿ b. Nuʿaym, the famous second-/eighth-century Medinan Quran reciter, who provided the impetus for this post.

When reading through the biographies, like the one above, write down the words— especially the verbs—that you are not familiar with. If absolutely necessary to obtain an inkling of comprehension, look up the definitions of select words while reading. But try your hardest to avoid looking up definitions at this point. Instead try to infer the meaning of unknown words from the context, an invaluable skill for gaining reading comprehension in a foreign language. Inferring the meaning of words may be easier than you think since the biographies concern individuals in your area of expertise. And you’ll get better at it with practice.

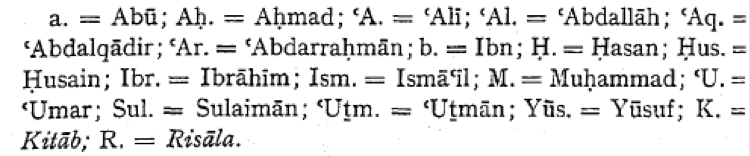

** Brief aside: You will notice that Sezgin regularly uses abbreviations, especially for names, which he derives from Brockelmann. You can find the key for Sezgin’s abbreviation system at the beginning of each volume, pictured below. Sezgin also regularly provides the citation for Brockelmann’s GAL entry. For example, see the beginning of Nāfiʿ’s biography above where we find: von Br. S I, 328 = “from Brockelmann, Supplement 1, page 328. Don’t worry, you will quickly become familiar with the abbreviations, some of which are just basic German abbreviations—e.g. “s.” = siehe / see; “S.” = Seite / page; “Jh.” = Jahrhundert / century; “vgl.” = vergleiche / compare; “eb.” = ebenda / ibidem. **

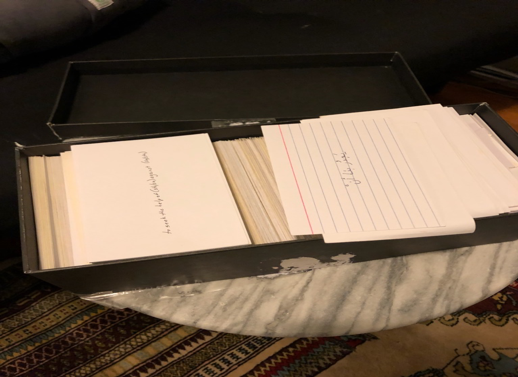

After you’ve read through a handful of biographies, look up the definitions for the list of unknown words that you wrote down and make vocab cards for each word or phrase. I still prefer handwritten vocab cards as the act of writing aids my memorization of definitions—and there’s evidence for this. Nevertheless, handwritten vocab cards can be inconvenient, so you may prefer to use a digital app such as Anki or iFlash, both of which I’ve enjoyed using for studying vocab on the go. Whether you are using handwritten cards or an app, the key to vocab acquisition is to review your Sezgin cards on a daily basis. Look at the L1, your native or stronger language, side of the card first and attempt to recall the German word from memory.

If you opt for handwritten vocab cards, I recommend this system: the day after you begin making German vocab cards from reading Sezgin’s GAS, review your cards. The ones you get right move to a second pile; the ones you get wrong or can’t remember stay in the original pile. Each day review your German vocab, moving the cards you remember correctly one pile to the right and the ones you don’t one pile to the left. I employ a five-pile system—an honest week’s work if you remember them correctly every day—and when I remember the words in the fifth pile correctly they get put in the “memorized box,” which contains vocab cards that I now know well, but still review on a monthly basis.

My box of Arabic vocab cards from studying in Sana’a in 2007.

So what does this have to do with Sezgin’s GAS? Well, Sezgin’s biographies of scholars abound with German vocabulary that is particularly relevant for the study of Arab-Islamic history and thought. His biographies also tend to be concise, his syntax is quite simple, and his sentences are short. For all these reasons, Sezgin’s GAS is excellent for practicing your German and learning field-specific vocabulary while also learning about the bio-bibliographic history of your specific research area.

You can, and should, also practice your grammar when reading Sezgin’s biographies. An effective way to do this is by applying the lessons from your chosen German grammar book to your reading. For instance, if you just completed a lesson on German pronouns and their declensions, then apply this lesson by identifying all the pronouns and their respective cases (i.e. nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative) in a few biographies. Or break down sentences into their component parts, identifying the verbs, adverbs, adjectives, nouns, and prepositions while noting verb tenses, gender, number, cases, and case endings.

If you are required to take a German reading exam, begin attempting to translate Sezgin’s biographies. When you are struggling with your translation, look at other biographies of the scholar from the Encyclopaedia of Islam or Encyclopedia Iranica or Wikipedia to look for clues on what Sezgin might be saying. And don’t get too hung up on translating the exact meaning of the biography at this point, instead shoot for the general meaning (al-riwāya bi-l-maʿnā) rather than a word-for-word translation (al-riwāya bi-l-lafẓ). There is also an Arabic translation of Sezgin’s GAS, which you can use to check your translations.

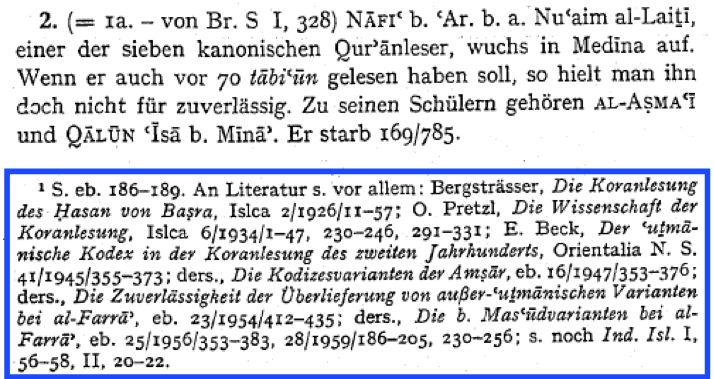

After you have read through Sezgin’s biographies in your area of focus, move on to reading his introduction to that section. This will be much more difficult than reading his short biographies, but you should now be familiar with the major figures in your respective field and with the pertinent vocabulary and terminology.

•••

Now comes the fun part: Diving into Sezgin’s bibliographical notes that are under every biography. My fellow graduate students, there are thousands, nay tens of thousands, of potential dissertation topics buried in these bibliographical notes.

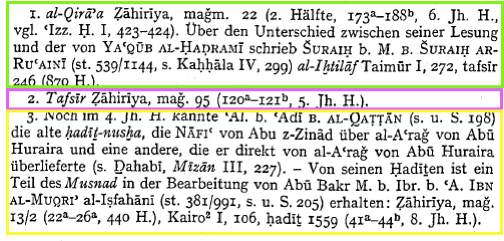

For an example of how Sezgin structures his bio-bibliographical entries, let’s return to Nāfiʿ b. Abī Nuʿaym’s biography. From Sezgin’s biography we learn the citation for Brockelmann’s entry on Nāfiʿ, Nāfiʿ’s name, and select details about his life: Nāfiʿ was one of the seven canonical Quran readers, he grew up in Medina, he supposedly learned Quranic recitation from seventy Successors yet he wasn’t considered reliable (in hadith transmission), among his prominent students were al-Aṣmāʿī and Qālūn, and he died in 169/785.

Underneath the biography, Sezgin provides a list of secondary-source studies that discuss the biographee (I’ve outlined them in blue). Many of these studies are in German, so you can keep practicing with more difficult texts. Sezgin’s lists are obviously outdated—the first volume of GAS was published in 1967—yet many of the studies that he references still hold water. Typically Sezgin provides a list of the extant medieval Arabic biographies of the scholar along with more recent biographies (outlined here in orange) directly after his short biographical entry; however, in the case of Nāfiʿ he switches the order. Sezgin’s list of biographies for each scholar tends to be relatively comprehensive and is an informative roadmap for further research into the respective scholar’s background.

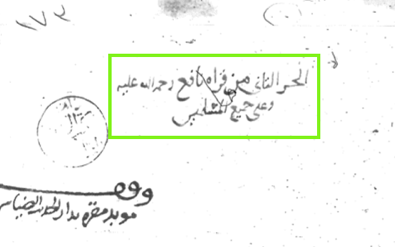

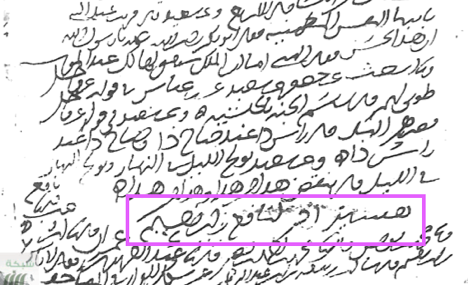

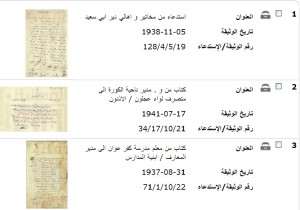

Next Sezgin provides a list of manuscripts written by, or attributed to, the scholar. As you’ll see below in the case of Nāfiʿ b. Abī Nuʿaym, Sezgin mentions works reportedly written by the scholar that are no longer extant. First, in green, we find the second part of Nāfiʿ’s treatise on the proper reading of the Quran, al-Qirāʾa, which is a fifteen-folio manuscript written down in the sixth/twelfth century and housed at the Ẓāhiriyya Library in Damascus. (Photocopies of the Ẓāhiriyya Library’s collection of majmuʿāt manuscripts can be found online here, and here is the link to Nāfiʿ’s al-Qirāʾa manuscript, which is located at the end of the majmuʿa.)

The second work (outlined in magenta) that Sezgin references is a fragment from Nāfiʿ’s Tafsīr, which is once again located among the majmuʿāt at the Ẓāhiriyya library. The final work is a hadith collection of Nāfiʿ (outlined in yellow). Sezgin first notes that al- Dhahabī referenced a nuskha of Nāfiʿ’s hadith transmitted by ʿAlī b. ʿAdī b. al-Qaṭṭān (d. 365/976) in the fourth/tenth century, which is no longer extant, before going on to cite two extant manuscripts of Ibn al-Muqrīʾ al-Isfahānī (d. 381/991), preserved in Cairo and Damascus, that contain a selection of Nāfiʿ’s musnad hadith collection. The Cairo MS of Ibn al-Muqrīʾ’s work was edited and published in 1991, a PDF of which can be found here. When applicable, Sezgin notes the edited editions of works, however, since the publication of the early volumes of GAS an incredible amount of manuscripts have been edited and published so it is always good to check whether a previously unedited MS has been published. The easiest way to do this is by doing a search on WorldCat and there’s a chance the published edition of the text may be available online at Waqfeya.

And just like that you’ve gone from working on your German reading comprehension using Fuat Sezgin’s GAS to finding unpublished manuscripts that may be central to your next research project. If you don’t have much experience working with Arabic manuscripts, I urge you not to be intimidated. For years I put off engaging with the expansive corpus of Arabic manuscripts because I thought that I needed formal instruction in codicology. Don’t make the same mistake as me![1][AH2]

•••

So to recap, if you are a student of Islamic history and thought who needs, or wants, to learn German, Fuat Sezgin’s Geschichte des Arabischen Schrifttums is a fantastic source for improving your reading comprehension because it uses vocabulary pertinent to the field, his syntax and prose is simple, and his sentences are short. By reading Sezgin’s GAS you will also get an overview of the first four-hundred years of scholarly history in your area of focus while learning about loads of unedited Arabic manuscripts that are begging for your attention. You may even alight upon your dissertation topic or next research project. And, frankly, we need more scholars to work on the Islamic manuscript tradition, so learn enough German to utilize Sezgin and throw yourself into the vast world of Arabic manuscripts.

•••

Rich Heffron (@richheffron) is a Ph.D. candidate in Islamic history at the University of Chicago and a lecturer in the Department of Philosophy and Religion at Ithaca College. His research focuses on the history of the Muslim scholarly community in early Islamic Syria.

[1] A good way to begin working with Arabic manuscripts is to find an entry in Sezgin’s GAS of a scholar who is of particular interest to you. Go to Sezgin’s bibliographical notes for the scholar and see if any of the manuscripts attributed to them are available online (e.g. the majmuʿāt collection of Ẓāhiriyya) and have been edited and published. Once you’ve gotten your hands on the manuscript and the published edition based off the respective manuscript, start reading through the manuscript and transcribing the portions you can make out. Then check your transcription of the manuscript against the published edition while noting the different editing decisions the editor has made. Read through a few folios a week in this fashion and you’ll quickly get accustomed to the scribe’s hand and you will be able to decipher more and more of the manuscript with less and less effort. If you want a broad introduction to the world of Islamic manuscripts, I highly recommend Evyn Kropf’s (@eckropf) meticulous and up-to-date research guide.

Orient-Institut Istanbul

Introduction

The library of the Orient-Institut Istanbul is a specialized research library dedicated to the study of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey in all its aspects (linguistics, history, literature and social sciences); and, to a lesser extent, to the Turkic peoples, languages, and literatures of Central Asia. The collection comprises currently about 48,000 monographic volumes in various languages (Turkish, German, English, Ottoman, French, Armenian, Russian etc.) and over 1,500 periodical titles. It offers access to e-books and e-journals as well as to database holdings. Readers can also access the Islamic Studies e-Book Collection by the provider Al-Manhal within the network of the institute. This collection comprises at the moment 2,035 titles, mainly in Arabic.

The Orient-Institut Istanbul is located in Cihangir, Istanbul, Turkey. Cihangir is a neighborhood in the close proximity of Taksim Square.

History

The institute and its library are an offspring of the Orient-Institut Beirut, whose researchers had to leave Lebanon in 1987 because of the civil war and found a temporary home in Istanbul. With the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the subsequent rise of interest in the Turkic world, the institute remained in Istanbul as a branch office of the Orient-Institut even after the directorate and some of its researchers were able to return to Lebanon in 1994. In 2009, the Orient-Institut Istanbul became an independent research institution. Since 2003, it has been affiliated with the Max Weber Foundation.

From the very beginnings, acquisitions had the objective of establishing a research library for Ottoman, Turkic, and Islamic studies in accordance with the academic profile of the institute. Its main aim has been to serve the purposes of the in-house researchers. Thus, acquisition is driven by the needs of current as well as prospective researchers, be it in the fields of history, literature, language, religion, culture, or society. This includes not only academic books and journals, but also primary source material. Accordingly, a great number of Ottoman books and journals as well as books and journals from the early Republican period have been purchased at antiquarian bookshops. In general, manuscripts are not part of the collection strategy. Since one of the objectives of the institute is the promotion of academic exchange between Germany and Turkey, relevant academic publications in German are acquired on a regular basis.

Collection

The library of the Orient-Institut Istanbul collects for the most part print material related to Turkey and the Ottoman Empire. Besides books and journals, we also collect music and documentary films on CD and DVD.

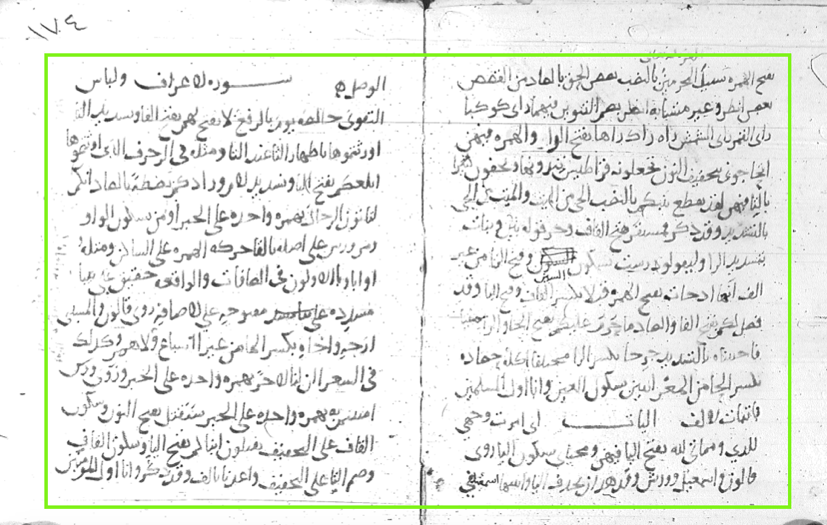

It is a highly specialized library with currently over 48,000 monographic volumes and a collection of more than 1,500 journals, 120 of them as currently running subscriptions. Our oldest monograph dates back to the 16th century.

The collection has its emphasis on the study of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey in all aspects (linguistics, history, literature and social sciences). It also includes literature concerning Turkish-speaking groups of the Ottoman Empire’s former territories, the languages of Turkey, the religions of the Ottoman Empire and “Turkish Islam.” The Turkic peoples, languages and literatures of Central Asia also fall under the purview of our collection. Publications on the history of Turkey before the time of the Seljuks are not acquired.

Besides printed material, with the establishment of the research field “Music in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey” in 2011 the library began to focus on literature on music as well as on audio material. In 2016, a collection from the late German journalist Birger Gesthuisen with more than 280 music CDs and records, especially from musicians in the North-Western European Gurbet, was donated to the library.

For the institute’s special research project on “New Religiosities in Turkey” between 2011-2017, a special collection was established that comprises currently about 2,700 volumes related to new religious movements, spirituality, superstition, occultism, esoteric belief, alternative healing methods, etc. Additionally, a comprehensive collection of journal articles and grey literature on the topic is currently being catalogued.

The Research Experience

All monographs and journals can be retrieved in our OPAC. Besides this, articles from edited volumes like conference proceedings and festschrifts available at the library are likewise retrievable.

Since the collection is currently spread out over six floors in two residential buildings, books are generally grouped according to their subject. In anticipation of the institute’s relocation to a building with a separate book repository, we have started to organize the books according to the numerus currens system since January 1, 2018.

Recently, some of the most fragile materials of the library were digitized. Those digital materials are hosted by Menalib, the Middle East Virtual Library. Since only very fragile publications are digitized, access to the originals is normally not possible.

Most of the library’s material is immediately available for the researcher, but those parts of the collection housed in the second building must be ordered a day in advance. This can be done directly through the OPAC by mail request.

The reading room offers seven reading spaces, one with a computer for catalogue research, etc.. WLAN is available.

The librarians speak Turkish, Armenian, German, and English.

Access

The library is open to the public from Monday to Thursday from 10am to 7pm and on Friday from 9am to 1pm. We are open in summer, but closed on official Turkish holidays, as well as Easter and between Christmas and the New Year.

The library is open to everyone without prior registration. Library users are asked to enter their name in our guestbook, which serves merely statistical purposes.

Reproductions

Library users are free to take photographs or use a book scanner free of charge within the limits of the copyright regulations. The book scanner is used with one’s own USB-stick.

Photocopies are permitted in accordance with copyright regulations. Originals are sent by our staff to a nearby copy shop for next-day delivery. The copy shop currently charges 0.15 TL per copy, plus tax, (December 2018).

Transportation and Food

The institute is situated in Cihangir, within walking distance from Taksim Square.

A lot of cafes, bistros and local restaurants (lokantalar) are nearby as Cihangir is an up-and-coming neighborhood, with accordingly elevated prices. Unfortunately, we don’t have the space to allow for coffee breaks or having lunch on our premises.

Miscellaneous

The library of the Orient-Institut Istanbul is a member of BiblioPera, a network of research centers in Beyoğlu. The heart of the network is its union catalogue. For more information, please click here.

The Orient-Institut Istanbul hosts lectures and symposia and organizes conferences together with academic partner institutions. The institute has a scholarship program for doctoral candidates coming from abroad for a research stay in Istanbul up to six months. The announcement is published annually on our website, usually in late autumn.

Future Plans and Rumors

The Orient-Institut Istanbul will move from Cihangir to the Tünel district within two to three years. The new location will be close to the Şişhane Metro station on Galip Dede Street. Her şey çok daha güzel olacaktır.

Contact information

Orient-Institut Istanbul

Susam Sokak 16/8

Cihangir, 34433 Istanbul

Tel. +90-212-2936067

https://www.oiist.org/en/bibliothek/

Map of location

Resources and Links

Here you can check which online journals you have to access within the premises of the Orient-Institut Istanbul.

On the library’s website, also find a list of relevant online resources, some freely accessible some only from the network of the institute.

Keyword Tags

Istanbul; Turkey; Early Modern; Modern; Printed; journals, newspapers; music

Biography

Dr. Astrid Menz is the head librarian of the library of the Orient-Institut Istanbul.

ORCID-ID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1741-3250

Centre des Archives Diplomatiques de Nantes (CADN)

The Centre des Archives Diplomatiques de Nantes (the Diplomatic Archives Center in Nantes or CADN) houses extensive collections of French diplomatic files from the 18th-20th centuries. Among scholars of the Modern Middle East, Nantes is most famous for its collections of documents produced by the French mandate in Syria and Lebanon, as well as the French Protectorates in Tunisia and Morocco. However, Nantes also contains thousands of boxes of French consular files from cities around the world. Additionally, the archive has files from several international organizations that France was involved in. Taken together, the CADN is an indispensable stop for anyone working on the Middle East or North Africa in the 19th or 20th centuries.

Continue reading “Centre des Archives Diplomatiques de Nantes (CADN)”

The Cairo Agricultural Museum and Library

By Taylor Moore

The Cairo Agricultural Museum complex, located right off of Salah Salem street in the neighborhood of Dokki, is a gem of object collections and archival holdings hidden in plain sight. Its under-utilized collections will be of interest to historians and social scientists working on agriculture, food, natural history, political economy, rural Egyptian history, and public works from the Pharaonic period until present day. The museum is also a rare find for scholars interested in material culture and museum studies in modern Egypt. Its exhibits stand as an archive in and of themselves. They provide material testament to developments in the natural sciences, anthropology, food science, visual culture, and curatorial practices as many of the collections and dioramas remain untouched since the first half of the twentieth century.

History

In 1930, King Fouad of Egypt established the Agricultural Museum in the Cairo suburb of Dokki in the palace of Princess Fatima, the daughter of the great Khedive Ismail. It is one of the first agricultural museums in the world—second only to the Royal Agricultural Museum in Budapest. The museum was officially inaugurated by King Farouk in 1938 when he selected the venue to host 18th International Cotton Congress. The Agriculture Museum was preceded by an array of agricultural expositions organized by the Khedival Agricultural Society (later Royal Agricultural Society), an organization determined to improve agricultural methods in Egypt, and “the lot of the fellah.” The society created a small agricultural museum in 1920. This initial collection was ultimately modified into a cotton museum, which later became a part of the “Fouad I Agricultural Museum” when it opened to the public (el Shakry, 2007).

The Museum’s initial collections consisted of an array of objects donated from scientific institutions throughout Egypt, including the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Agricultural Society, and the Egyptian Department of Antiquities. Hungarian artists oversaw the creation and curation of the museum’s first displays (Davies 2014). With its holdings “lying halfway between a museum of natural history and a purely agricultural museum,” the Egyptian government mobilized the museum as cultural and educational space for the public until the 1960s (Ghawas, 1972). For the next thirty odd years, the museum was essentially left for dead. Most of its artifacts and object collections were relocated to storage, and the exhibition halls were transformed into makeshift government offices, presumably for Ministry of Agriculture staff. In the 1990s, restoration projects began in earnest. As they were completed, sections of the museum were slowly reopened to the public beginning with the Hall of Ancient Egyptian Agriculture and the Cotton Museum in 1996. Currently, the museum complex is composed of seven exhibition halls (the museum pamphlet refers to these entities as small museums, or mutahif), a library, research laboratories, greenhouses, and a cinema. The grounds surrounding the museum have been maintained as a beautiful garden space, with two Pharaonic-style gardens located near the entrance to the Hall of Ancient Egyptian Agriculture.

Collections

As mentioned above the Cairo Agricultural Museum boasts seven exhibition halls which depict varying topics in natural history and agricultural science. The majority of the museum’s labels are in Arabic, however some exhibits provide English translations.

1. Scientific Collections

The Scientific Collections Hall is the oldest in the museum. The first floor is dedicated to ethnographic materials that depict the social and economic lives of the Egyptian fellahin. The most stunning exhibits of this building are the large, life-size dioramas of a rural wedding procession, and a village souk complete with a community forn, a café with galabiyya-wearing men laughing while smoking shisha, and even a female fortune teller reading shells. There are also rooms specializing in rural handicrafts, “habits and customs,” and the High Dam. The second floor houses a large natural history collection of taxidermy animals native to Egypt and Sudan, with rooms specializing in the life-cycles of domestic farm animals, insects and crop pests, as well as a room of popular Egyptian products and manufactured food goods from the 1940s and 1950s.

2. Botanical Revolution Hall

This hall, also referred to as the “Plant Kingdom Museum,” was established in 1935. Its

exhibits depict Egypt’s field crops, horticultural and garden plants, and popular agricultural machinery. The first floor specializes in grain crops such as wheat, barley, corn, and rice, and also has a room on onions and garlic. The second floor specializes in fiber crops, and rooms on fruits, vegetables, legumes, and more.

3. The Cotton Museum

In many aspects the original collection of the Agricultural Museum, the Royal Agricultural Society organized the Cotton Museum in 1920, and opened it to the public in 1926. The collections in their most recent state were inaugurated in the Cairo Agricultural Museum in 1996 on Eid el Fellah (a feast day commemorating the victories of the peasantry and the implementation of Nasserist agricultural reforms after the 1952 revolution). The collections explore the importance of the cotton crop over the long duree of Egyptian history in its many forms from field to finished product, and include rare cotton the seeds and fibers from varying species of cotton crop grown around the world.

4. Ancient Egyptian Agriculture

This collection highlights role of the Nile River and the importance of agriculture in the economic, social, and spiritual realms of Pharaonic civilization. Many of these collections were acquired between 1932 and 1938 as donations from the Egyptian Museum and the Egyptian Department of Antiquities. Cappers and Hamdy (20007) provide original catalogue entries for specimen in this collection as well as some in the “Greek, Coptic, and Islamic” collections below.

5. Agriculture in Greek, Roman, Coptic, and Islamic Periods

These collections represent the second stage of development in early Egyptian agriculture

from 332 BC, when Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, until the rule of Mohammed

(Mehmet) Ali Pasha in 1805. However, the majority of materials are concentrated in the Greek and Roman periods. They highlight the role of plants in society (from popular field crops to medicine), the raising of livestock, and the social lives of the peasant classes at in these periods.

6. The Syrian Hall

This exhibit, inaugurated on July 31, 1961 commemorates Egypt and Syria’s short-lived union in the form of the United Arab Republic from 1958 to 1961. Its contents include information on trade between the two countries, and provide a collection of Syrian handicrafts, produce, and rural life.

7. The Egypt-China Friendship Exhibition

Opened in 2013, this exhibit is composed mostly of art and ceramics donated from China

to illustrate the thriving political relationship between Egypt and China.

8. Library

The museum’s library is a quaint two-floor building with an array of books, periodicals, and maps ranging from the mid-nineteenth century until the early 2000s. The subjects of the collection focus on a variety of agriculture and “agriculture-adjacent” materials such as botany, horticulture, public works, livestock, geography, and the social and economic aspects of rural life. Some examples of publications held in the library include volumes of Mémoires Présentés à l’Institut d’Egypte from the 1880s until the 1930s, yearly reports from the Department of Public Works from the 1880s onwards, and a Ministry of Agriculture periodical entitled Zamīl al-Fallāḥ published in the 1930s. Certain publications of the Ministry of Agriculture can also be found here, however most of those materials are held in the library of the Ministry of Agriculture and the National Agricultural Library (both located down the street from the Agricultural Museum.) As far as I know, this collection has not been catalogued and I was only able to conduct a cursory survey of the holdings during my research there. Future researchers may find more than detailed in this review.

Research Experience

The Agricultural Museum and Library is easily accessible to researchers. Those that speak Arabic will have an easier time of things, although many of the museum and library staff know some level of English. As of 2016, the entry fee to the main collection halls, library, and gardens was 5 LE, with an extra fee to enter the Hall of Ancient Egyptian Agriculture. However, researchers must note that depending on the day, and maybe even the hour, particular halls or exhibitions may be locked and/or closed to visitors. Generally, the main exhibits in the natural history, or scientific collections, and the library are always open to the public.

The library, located near the research laboratories a ways off from the main buildings, is a charming and pleasant workspace. More often than not, researchers will have the reading room to themselves, sharing the space with only a handful of library staff. Madame Azza is the main librarian. After signing your name in a logbook, Madame Azza will ask you what kinds of materials you are interested in. You can give her specific texts or vague subject and she will bring the exact text, or texts that might interest you out to the reading room for you. If you are lucky, she may allow you to wonder through the upstairs stacks yourself. This is the area where most of the old periodicals, governmental reports, and “rare books” from 1880 until 1950 are housed.

Currently, there is neither known catalogue for the ethnographic and natural history collections, nor the holdings in the library. I was also not able to find information on the provenance of the museum’s collections. However, as of June 25 2017 the Egyptian Central Department of Archaeological Acquisitions examined and registered over 1,000 of the Agricultural museum’s ancient animal and geological artifacts. There may be a way to access the catalogue or reports from this investigation. Those wishing to work with certain objects or collections should get in touch with the museum staff directly. Although the museum’s pamphlet provides a phone number and an email address for researchers to direct their inquiries, it is recommended that scholars make requests in person to the museum staff who may put you in touch with the museum director. It is advised that researchers provide a statement in Arabic addressing their academic affiliation, research interests, and the collections they are interested in working with.

Unlike other archives in Egypt, such as Dar al-Watha’iq al-Qawmiyya (The Egyptian National Archives) and Dar al-Kutub (The Egyptian National Library) where photographs of materials are forbidden, or in the Egyptian Geographical Society’s Ethnographic Museum where photographs of the exhibits can be taken for a fee, the Cairo Museum of Agriculture allows researchers to take pictures of materials in both the library and the museum for free.

Transportation

The Cairo Agricultural Museum is located in the neighborhood of Dokki. The museum is an easy 25 minute walk from the Behouth (Dokki) or the Opera (Zamalek) metro stations. Given the museum’s location right off of Salah Salem, it is easily accessible via taxi, Uber, or Kareem as well. Researchers can simply direct them to “al-mathaf al-zara’i” or “wizarat al-zira’a.” There are a handful of restaurants, cafes, and kushks located near the museum, particularly in the directions of the Dokki Shooting Club (Nadi Es-Sid) and Mohandessin.

Contact Information (according to museum pamphlet):

Telephone: +2(02)33372933 and +2(02)37616874

Website: www.agrimuseum.gov.eg

Email: agri.museum@yahoo.com

Hours: Sunday through Friday 9AM-2PM; The museum is occasionally closed for maintenance and hours are liable to change.

Resources and Links

Here is a link to the Cairo Agricultural Museum Pamphlet and a link to the Cairo Museum of Agriculture Booklet.

The most in-depth descriptions of the museum, its history, and its exhibitions can be found in

Al-Mathaf Al-Zira’i Kama ’Arfithu (elKhattab, 2003), located in the museum’s library collection, Guide du Musée Agricole Fouad I , and the Bulletin of the Royal Agricultural Society.

Additionally, some of the most useful sources that cover the history of the museum, as well as its current state and collections are below. (I have also included limited secondary literature regarding the general history of agriculture in twentieth century Egypt as it pertains to the history of organizations such as the Ministry of Agriculture, the Fellah Department in the Ministry of Social Affairs, and the Royal Agricultural Society):

Davies, Claire. “The Anatomy of Melancholy: Cairo’s Lost Agriculture Museum.” Bidoun, no. 14 Objects: A Treasury of Bidounish Wonders (Spring/Summer 2008). https://bidoun.org/articles/the-anatomy-of-melancholy.

El Shakry, Omnia S. The Great Social Laboratory: Subjects of Knowledge in Colonial and Postcolonial Egypt. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2007, pp 125-126.

Ghawas, M. H. El. “The Agricultural Museum, Dokki.” Museum International 24, no. 3 (January 12, 1972): 174–76.

Hassan, Fayza. “The Forgotten Museums of Egypt.” Museum International 57, no. 1/2 (May 2005): 42-48.

Johnson, Amy J. Reconstructing Rural Egypt: Ahmed Hussein and the History of Egyptian Development. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2004.

Meyer, Sara-Duana. “The Dimly Lit Marvels of Cairo’s Agricultural Museum.” Mada Masr (blog).. https://www.madamasr.com/en/2015/05/14/feature/culture/the-dimly-lit-marvels-of-cairos-agricultural-museum/.

Rivlin, Helen Anne B. The Agricultural Policy of Muhammad ’Ali in Egypt. Y First edition edition. Harvard University Press, 1961.

The most information regarding the museums collections focuses mainly on the Ancient Egypt collections. The texts below produce in depth information about their research experience at the museum, detailed information about the objects examined, and attempt to catalogue them and/or cite a catalogue given to them during their research:

Bober, Phyllis Pray. Art, Culture, and Cuisine: Ancient and Medieval Gastronomy. University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Cappers, R.T.J, and R. Hamdy. “Ancient Egyptian Plant Remains in the Agricultural Museum (Dokki, Cairo).” In Fields of Change Progress in African Archaeobotany, 165–214. Groningen Archaeological Studies 5. Barkhuis, 2007.

Crane, Eva. The World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting. Taylor & Francis, 1999.

Darby, William Jefferson, Paul Ghalioungui, and Louis Grivetti. Food: The Gift of Osiris. Academic Press, 1977.Ikram, Salima. Choice Cuts: Meat Production in Ancient Egypt. Peeters Publishers, 1995.

Taylor M. Moore is a PhD Candidate in Modern Middle Eastern History at Rutgers University. Her dissertation explores the entangled histories of magic, medicine, and museums in early twentieth century Egypt.

Jafet Library, the American University of Beirut (AUB)

When historians refer to ‘training,’ we often refer to being able to read an archive and understand how the source itself fits into the grander scheme of the archive. But part of the problem, at least in Middle East and North African studies, is having archives to read into at all. The last two decades have witnessed multiple archive crises in the region. Archives have been rendered inaccessible, often by conflict, in the case of Syria and Iraq, or sources have been deliberately removed from archives by security states, such as the Israeli State Archives; Lebanon’s national archives, meanwhile, are under ‘renovations’ and there’s little word on when they might be accessible to the general public. But perhaps the problem is that we’re not thinking archive-first: we dive into topics without thinking of the availability of sources. Another layer of training we might receive is to construct projects while thinking source-first and readily reading available sources against the grain.

Jafet Library at the American University of Beirut (AUB) is one such repository of primary sources that might inspire researchers to think critically when building their own collections of sources. The Library has an impressive microfilm collection of Arabic-language periodicals. Furthermore, its Archive and Special Collections have accumulated some noteworthy unique documents, including private papers of the region’s elites.

Continue reading “Jafet Library, the American University of Beirut (AUB)”

National Library in Amman

- Taxi: the more expensive, although somewhat more convenient option. From nearby neighborhoods (Shmeisani, Tila’ al-Ali, Jabal Weibdeh, Jabal Amman, Abdali, Abdoun, the University) this should cost you between 1-2 JD, though from beyond 6th Circle, expect to pay a little more. Tell the taxi driver to let you off at the Royal Cultural Center or the Regency Hotel, preferably near the pedestrian bridge. At the pedestrian bridge, follow Haroun al-Rashid St. until you get to the library (about a minute) on the left.

- Service: only viable if you’re coming from downtown or Weibdeh. Take the Abdali service, get off at Duwar al-Dakhiliyeh and walk in the opposite direction till you get to the first pedestrian bridge (after the Regency Hotel). At the pedestrian bridge, follow Haroun al-Rashid St. until you see the library (about a minute) on the left.

- Bus: this option is really only viable if you’re coming somewhere off University Street. If coming from Abdali, take the bus going to the University or Sweileh and tell the conductor you’re getting off at the Royal Cultural Center. If coming from the University, take the bus going to Duwar al-Dakhiliyeh and tell the conductor you’re getting off at the Royal Cultural Center. At the pedestrian bridge, follow Haroun al-Rashid St. until you get to the library (about a minute) on the left.

Milli Kütüphane

Written by Elise Burton

Note: This review was written in June 2015 following research in Milli Kütüphane between March and May 2015. Web links have been updated, but other details (e.g. photocopying fees, cafeteria prices) may no longer be accurate. Hazine readers are invited to submit updated information.

Turkey’s national library, near the center of Ankara, has a diverse collection of materials dating from the early Ottoman Empire to the present. The bulk of the collection, namely monographs and periodicals, is of interest to historians specializing in the late Ottoman and early Republican periods. With over 27,000 manuscripts from provincial Anatolian collections, this library is also the second-largest manuscript repository in Turkey after the Süleymaniye Library in Istanbul. The digitized online collections, including the manuscripts, Ottoman periodicals, and audiovisual material, may also be useful to researchers in earlier periods of Ottoman history, Islamic studies, as well as music, film, and art history.

History

The Turkish government began to collect materials for a national library in 1946 under the auspices of the Turkish Ministry of Education. This collection was first opened to users in 1948 with a catalog of 60,000 items, though the National Library was not established as a formal legal entity until 1950. The original intention was for the library to become a repository for copies of every publication produced in Turkey, but this plan was never completely realized. Nevertheless, as the collection and number of users continued to expand in subsequent decades, planning for the much-larger building that currently houses the collections took place between 1965-1973. Construction of the present building was completed in 1982 and opened to the public in the following year.

Collections

Although it does not hold every Turkish publication ever printed, the National Library surely holds the most comprehensive collection of printed material in late Ottoman Turkish (about 80,000 items) and modern Turkish (about 1 million items), with particular strengths in periodicals (including over 230,000 journals and newspapers). Some of these items are available on microfilm. The National Library has sizeable numbers of monographs in Arabic, English, French, German, and Persian, but primarily of more recent publications. The library also holds many CDs and DVDs, including some hidden gems like oral histories, but these collections are poorly identified; the oral histories, for example, seem to have been collected in a single unidentified project and the subjects are mostly Istanbul professionals speaking to unnamed interviewers in 2010. The National Library’s most unique collection is certainly the Atatürk Document Repository (Atatürk Belgeliği), which includes a wide array of textual and visual materials related to Kemal Atatürk’s life and legacy. This collection, open to users since 1983, contains 15,011 items ranging from books, magazine and newspaper clippings to paintings, sculptures, photographs, and newsreels, to personal items like passports, badges and lottery tickets.

The National Library provides some excellent online resources. Manuscripts, periodicals in Ottoman script, old gramophone recordings, and visual art materials (particularly paintings and film posters) have largely been digitized and are freely available online (links below). Anyone can search the digitized catalogs, but to view the results, you must create a free user account. There is a per-page charge for downloading digitized images. Due to the rather cumbersome process of working at the library in person, I would highly recommend that researchers interested exclusively with such materials register online and work from elsewhere

Access

Registration. No one can enter the library without a user card. There is a pre-registration form on the library website, which can be submitted before you arrive. Bring your passport to the user registration desk (past the metal detector at the entrance, and around the left-hand corner) to have your photo taken and receive your user card. If you did not have a chance to pre-register online, you can fill out the same form at a computer kiosk next to the registration desk.

If you’re a Turkish citizen, or if you’re a foreigner on a residency permit or research visa with your paperwork cleared in advance, this is the entire process. If you’re on a tourist visa, you’ll be sent off to an office down the hall to fill in the standard research permit forms to approve you for a foreign researcher (yabancı uyruklu araştırmacı) user card. The staff is generally monolingual in Turkish, so if you have any trouble communicating, get someone to lead you down to this office, where there are a few staff members who speak English. The forms, written in Turkish and English, are straightforward and you do not need a letter of introduction; your passport and, if applicable, an ID card from your institution will be all you need. Your forms should be approved on the spot, and you’ll be sent out to hand copies to another office and go back to the front registration desk, where you will finally get the user card. Cards are issued for periods ranging from three months to one year. My three-month card cost 5 TL.

Getting inside. Now that you have your card, get in line for the machines in the front lobby that assign spots in one of the six general reading rooms (one of these is reserved for professors, and another for high school students). Unfortunately, no one can enter the turnstiles into the library without a seat assignment, even if you intend to spend your time in a room without assigned seating (such as the rooms for viewing periodicals, microfilms, Atatürk documents, etc). The machines are straightforward: insert your user card, and you’ll be shown which rooms have available seating for you to select. It doesn’t matter much which room you choose unless you specifically want to use books printed in Ottoman script, in which case you must select the İbn-i-Sina Reading Room. After you have made your selection, take the receipt for your seat number, and your card will now unlock the turnstiles and permit access to the rest of the library.

When planning your research time, note that during the academic year, the library is overrun by Ankara’s large undergraduate population, and all the reading rooms tend to fill within an hour of opening. Once the library is full, it can take 1-2 hours or more of waiting in line by the entry machines before a slot opens up for you. To avoid this frustration, I recommend arriving up to a half hour before opening time (a line will already be forming). The other effect of this system is that you will not want to exit the library for longer than a ten-minute break until you are finished for the day. Ten minutes after you exit the front turnstiles, your seat assignment lapses and is made available to others waiting. Plenty of users duck outside to smoke a quick cigarette, but for food, you’re stuck with the library cafeteria (there’s barely enough time to cross the street to get to the next closest source of food).

During the summer vacation (mid-June to August) the competition for space is not quite as cutthroat; only those specifically using Ottoman-language materials and therefore needing space in the relatively small the İbn-i-Sina room may want to arrive early. You can monitor how full the reading rooms are directly on the library’s homepage under the heading “Okuma Salonları Doluluk Oranları.”

Requesting materials. In general, everything is requested via paper forms, and you can only submit three of these at one time (six for professors). There are computers on the second floor with access to the online catalog. For books, use the forms next to these computers and submit these to the “Okuyucu Bankosu” on the second floor. For periodicals or microfilm/non-book materials, go to the desk inside the periodicals room on the ground floor or the “non-book materials center” on the lower floor to fill out and submit the appropriate forms. Materials generally arrive between fifteen and twenty-five minutes after your request is received. The desk will hold on to your user card while you have the books, and give it back when you return them. Since you cannot exit the turnstiles without your user card, this is their way of preventing book theft. After hours and on weekends (only), you can request books online from the library website.

Reproductions

There is a photocopying service across from the Okuyucu Bankosu. As of May 2015, prices were 5 kuruş per A4 page (10 kuruş double-sided) or 10 kuruş per A3 page (20 kuruş double-sided). I did not use the service, but it appears that requests are fulfilled very quickly.

I never found any written policy on the use of digital cameras on modern materials, but I used mine to photograph twentieth-century books and periodicals in the reading rooms in clear view of staff and no one seemed to mind. Those working with older (Ottoman) or special materials should ask the reading room’s staff to confirm whether digital photography is acceptable for those items, especially since photocopying these materials is explicitly forbidden. Digitized materials and microfilms can be copied onto CDs/DVDs by staff; there is supposed to be a fee, but when I requested a DVD copy of an oral history recording, the staff refused to charge me anything.

According to the library website, researchers outside of Ankara can order materials to be scanned/copied and sent to them. I have no experience with this service.

Internet access: Free wifi seems to be available, but a Turkish mobile number is required to register for access to the wifi signal, so I was not able to test it. Wired internet access is available on the thirty computers of the “Interactive Salon,” really an open space on the same floor as the Okuyucu Bankosu. Access to these computers is granted by a machine that scans your user card, which limits you to one hour of internet use per day, and further prevents you from using these computers while in possession of any library books.

Food

Every floor has vending machines for bottled water and hot coffee/tea (only water bottles are allowed in the reading rooms). There is a cafeteria on the lower floor that sells simit and packaged snacks, hot and cold drinks, and basic hot meals (tost, köfte, spaghetti, salads and the like). Prices are low (up to 6 TL for a meal) and so is the quality of the food. Pay the cashier to the right of the entrance before taking your receipt to the food line on the left. Since there is no locker system, anyone who would rather pack their own lunch to eat in the cafeteria should have no problem doing so.

Getting there

The National Library is well served by public transit. It has its own Metro station on the new Kızılay-Koru line, which is definitely the most convenient option for anyone approaching from the east through Kızılay (Ankara’s transit hub) or the west from METU or Bilkent (Ankara’s main English-medium universities). There are also many bus and dolmuş lines departing from Ulus and Kızılay that stop in front of the library on İsmet İnönü Street.

Contact

Address: İsmet İnönü Caddesi/Bahçelievler Son Durak, 06490 Çankaya/Ankara

Phone: +90 312 212 62 00

Fax: +90 312 223 04 51

Email: bilgi@mkutup.gov.tr

Hours: Mon-Fri, 9:00-0:00; Sat-Sun, 9:30-22:00

(New user registration: weekdays, 9:30-12.30 and 13:30-16:30; materials fetching: weekdays, 9.30-17:00)

Useful Information and Links:

Digital Collections (manuscripts, Ottoman periodicals, visual arts)

Information on Ankara’s bus system

Elise Burton is the Associates’ Research Fellow at Newnham College, Cambridge. She completed her doctoral studies at Harvard University in 2017 and her current research focuses on the history of genetics research in Iran, Turkey, and Israel since the First World War.