Written by Melis Taner

The Chester Beatty Library (Leabharlann Chester Beatty) contains Oriental and Western books and manuscripts bequeathed by the private collector Sir Alfred Chester Beatty (1875-1968). Located on the grounds of Dublin Castle, the library houses one of the finest manuscript collections of Islamic and East Asian material in Europe and is especially well known for its illustrated manuscripts.

History

Sir Chester Beatty was a mining magnate who at an early age began to collect stamps and Chinese snuff bottles. Over time he began to collect European and Persian manuscripts. Following a trip in 1914 to Egypt, he became interested in Arabic materials and acquired several copies of the Quran. His collection grew and came to include Japanese and Chinese paintings after a trip to Asia in 1917. Sir Chester Beatty moved to Ireland in 1950 and there he built a library. His personal collection was bequeathed to the public after his death in 1968. The collection boasts manuscripts, single folios, scrolls, textiles and decorative objects from East Asia, Armenia and Western Europe in addition to over 4,400 Islamic manuscripts. The library’s aim is to preserve and display rare materials belonging to the collection of Sir Chester Beatty and to make them available to the public.

Collection

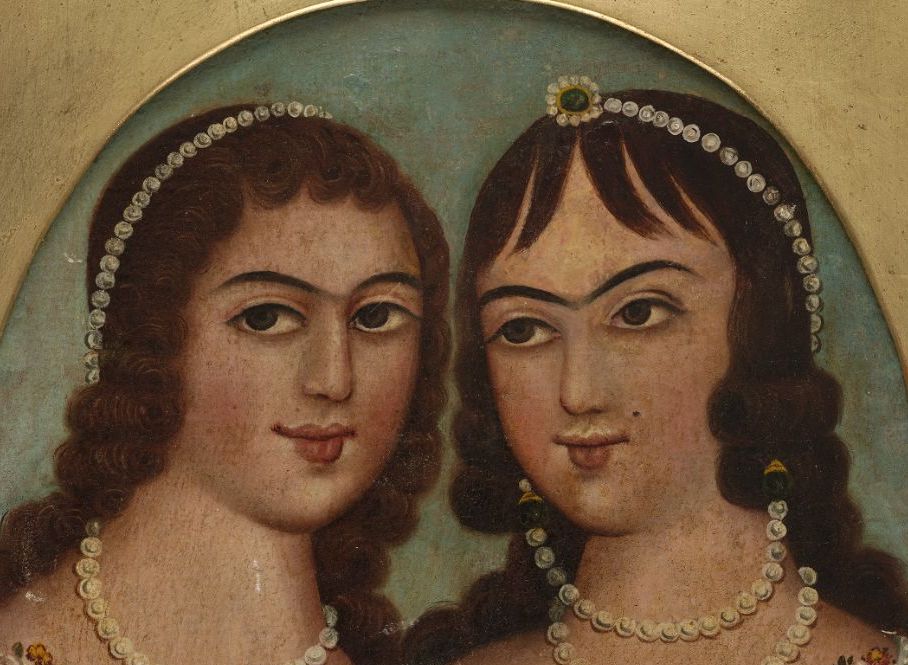

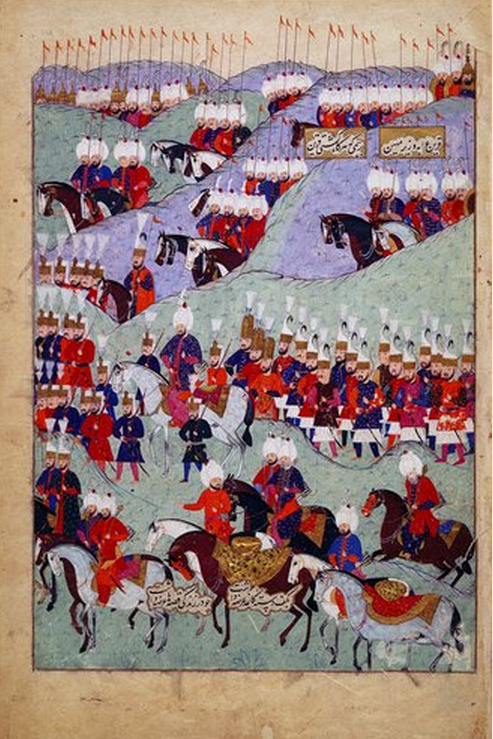

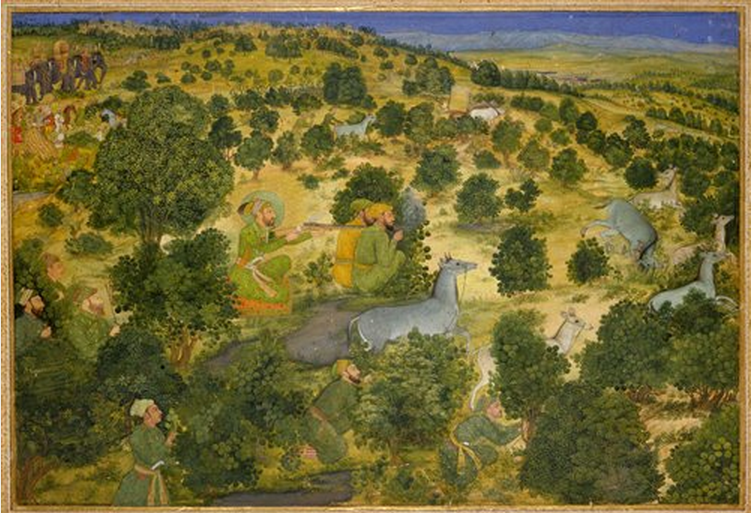

The Islamic manuscripts in the collection range in production date from the eighth century to the twentieth century. The majority of the collection is made of some 2,650 Arabic manuscripts, most of which are unillustrated and range in topic from history, religion, jurisprudence to astronomy and medicine. There are 260 Qurans in the collection, which boasts an illuminated Quran copied in Baghdad in 1001 by the famed calligrapher Ibn al-Bawwab. In addition, there is a large collection of Mughal manuscripts and paintings, produced during the reigns of Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan. The smaller collection of over 300 Persian manuscripts represents fine examples of illustrated literary works, including a luxurious copy of the Gulistan of Saʿdi (MS 10) made for the Timurid ruler Baysunghur. The collection of Turkish manuscripts comprises the smallest group among the Islamic materials and consists of around 160 manuscripts in Ottoman Turkish and Chaghatay. While a small collection in general, the quality of material preserved is very fine in terms of condition and decoration, and is a great resource for art historians in particular.

An e-book version of the guide to the collections is available for download on iTunes for $12.99. Printed catalogs of the Islamic collections are available for study in the reading room. The main sources for the field of Islamic history and art are the catalogs of Turkish and Persian manuscripts by Vladimir Minorsky and A. J. Arberry. Arberry’s eight-volume catalog of the Arabic collections are available electronically on the library’s website. Thomas Arnold produced a catalog of the collection’s Indian manuscripts. For the collection of Qurans, one can consult A. J. Arberry’s handlist of Qurans held at the Chester Beatty Library (please see below for references to all of catalogs cited here). While unpublished, researchers may also consult a folder that includes recent acquisitions.

Vladimir Minorsky’s 1958 catalog of the Turkish manuscripts and miniatures is organized with an eye to the style of painting as well as the language of the text. Thus, the illuminated Persian Mathnawi of Rumi is included in the catalog of Turkish manuscripts on account of the style of its illumination. On the other hand, a manuscript made for a Turcoman ruler, with a text in a Turcoman dialect, and paintings that are closer to Persian art than Turkish art, has also been included in this catalog on account of its language. The Turkish collection includes early works such as the Sulaymannama (T.406) composed and transcribed for Bayezid II (not to be confused with the late sixteenth-century History of Sultan Sulayman (Tetimme-i Ahval-i Sultan Suleyman, T.413), a late fifteenth-century deluxe copy of the Divan of Hidayat (T.401), and the fourth part of the late sixteenth-century Siyer-i Nebi (T.419). In addition, there are several manuscripts that contain maps and paintings of holy places, astrological manuscripts, as well as single folios and albums. There are several eighteenth-century copies of Dalail al-Khayrat; a late eighteenth-century illustrated account of El-Hacc Muhammed Edib Efendi b. Muhammed Derviş’s pilgrimage between 1779 and 1780. Along with illustrated and illuminated manuscripts, there are also several waqfnamas, such as that of Davud Ağa, former chief eunuch, or that of the princess Fatima Sultan, daughter of Murad III.

Minorsky’s catalogs are quite accurate and provide a detailed description of the manuscripts, including information about the author, codex size, folio number, binding, script, the name of the scribe, copy date, and provenance, whenever possible. When dealing with anthologies and albums, Minorsky provides information on individual sections and their folio numbers. The catalogs also include an index of personal names, places and tribes, as well as a selection of images. In addition to these catalogs there are dictionaries and reference materials relating to book collecting, bookbinding, calligraphy, Islamic art, East Asian art, Christianity and Buddhism in the reading room.

In 2011 the Chester Beatty Library launched an online and interactive Islamic Seals Database of seal impressions found in the library’s collection of Arabic manuscripts, set up as part of the library’s Arabic Manuscripts Project. The project is still in progress and will include images of seals from the library’s Islamic collection. The researcher or the visitor to the site may contribute by adding information, thus enlarging the database.

Research Experience

The collection is not digitized but researchers may view the originals in the reading room. The reading room operates on an appointment basis so it is most often quite empty and very pleasant to work in, with a large desk and cradles provided for manuscript support. As the reading room works on an appointment basis, the manuscripts are already on reserve for the researcher when he or she arrives. Should the researcher wish to see other manuscripts, they are brought out a few minutes after the request. There is no need to fill out any forms. In the reading room there are two librarians on duty and they have to be present while the researcher views the material. Should one or both librarians have to leave, a guard takes their place. In general, the researcher is not required to use gloves but cradles are suggested when necessary.

Access

The reading room is on the second floor of the library and is open from 10:00 to 13:00, and 14:15 to 17:00 Monday to Friday. The library is closed between December 24 and 26, as well as New Year’s Day, Good Friday, and any public holiday that falls on a Monday. From October to the end of April it is also closed on Mondays. It is important to contact the curator, Dr. Elaine Wright, well in advance as the reading room works on an appointment basis. While there is some flexibility in scheduling further sessions, it is best if the researcher contacts the curator for each session in advance in order to avoid any problem that may arise if the reading room is used for another event. One may contact the curator via e-mail with a description of one’s research and background as well as at least some of the manuscripts he or she would like to see. Once the researcher has an appointment through correspondence with the curator, it is quite easy to access the reading room. The guards at the entrance to the library will point the researcher in the right direction. There are lockers at the entrance (which require a 1 euro deposit), where one can leave personal belongings. There is no internet access in the reading room. The library is wheelchair friendly but it must be noted that currently there are problems with the lift service.

Reproductions

Photography is not allowed but digital reproductions for publication purposes are available on request. Reproductions for publication tend to be quite pricey at 17 euros per image. For a new photograph, it is 50 euros. There is also a handling fee of 21 euros if the images or microfilms are sent to the address. However, the curator is kind enough to provide lower quality images for free (up to 20 images) for study purposes only, if they are readily available.

Transportation and Food

The library is located very centrally, within Dublin Castle, close to Dame Street and Christchurch Cathedral. Dublin is quite small and walkable but bus routes are also available (lines 13, 40, 123, 27, 77a and 150). As the reading room closes for lunch, one may need to pack a lunch or go to one of the many nearby restaurants and cafes. The Silk Road Café, located within the library/museum, provides Middle Eastern and Irish food and has a good selection of vegetarian dishes. There are plenty of options nearby as well, from fish and chips stands to cafes, especially on Dame Street. The library also regularly holds exhibitions, which make for pleasant lunchtime perusing. The entrance to the library and museum is free. While the collection is quite small in comparison to some other manuscript libraries, the quality of materials is very high and it is a great place to work with the very obliging librarians and curators.

Contact information

Chester Beatty Library

Dublin Caste, Dublin 2

Phone: (+353 1) 407 07 50

Resources and Catalogs

Chester Beatty Library main site

Arberry, A.J. The Chester Beatty Library: A Catalogue of the Persian Manuscripts and Miniatures. V.Minorsky. Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co. Ltd. 1959-1962.

Arberry, A.J. The Koran Illuminated: A Handlist of the Korans in the Chester Beatty Library. Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co. Ltd. 1967.

Arberry, A.J. The Chester Beatty Library, A Handlist of the Arabic Manuscripts, Dublin, 1955-64. Volume 1, Ar 3000-3250.Volume 2, Ar 3251-3500. Volume 3, Ar 3501-3750. Volume 4, Ar 3751-4000. Volume 5, Ar 4001-4500. Volume 6, Ar 4501-5000. Volume 7, Ar 5001-5500. Volume 8, Indices.

V. Minorsky. The Chester Beatty Library: A Catalogue of the Turkish Manuscripts and Miniatures. Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co. Ltd. 1958.

Wilkinson, J.V.S.. The Library of A. Chester Beatty, a Catalogue of the Indian Miniatures. London: Oxford University Press, 1936.

__________________________________________________________________

Melis Taner is a doctoral candidate in the History of Art at Harvard University

Cite this: Melis Taner, “Chester Beatty Library,” HAZINE, 21 Feb 2014, https://hazine.info/2014/02/21/chester-beatty-library/