Written by Dzenita Karic

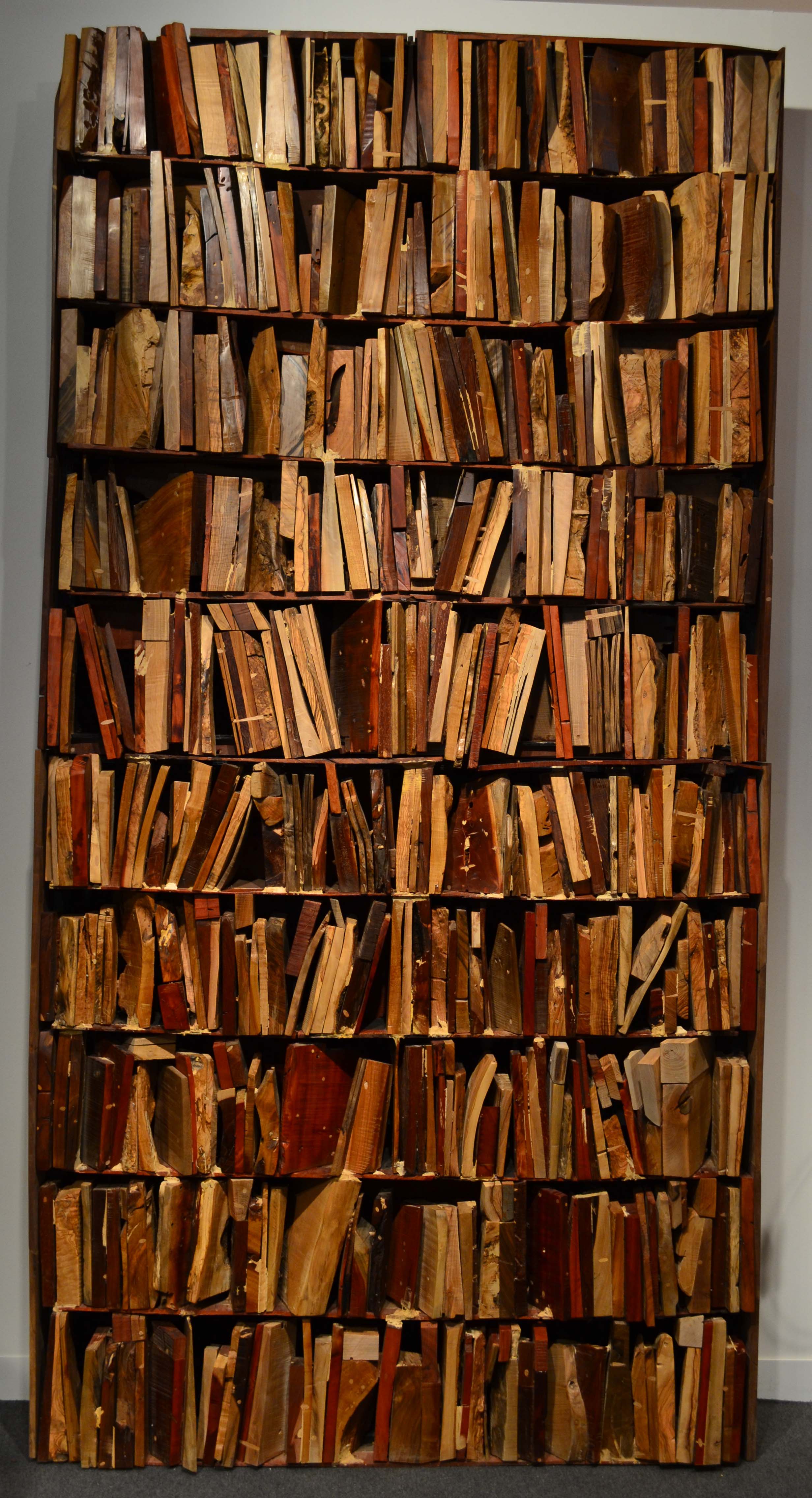

The Institute for Oriental Studies in Sarajevo (Orijentalni institut u Sarajevu) is a public research institution dedicated to the study of the Arabic, Turkish and Persian languages and literatures, both in general and, more specifically, for Bosnia’s Ottoman past. It was formerly one of the most important institutions for conducting research on the Ottoman heritage of the former Yugoslavia, although today, regrettably, it is better known for its most tragic fate: it was burnt down to the ground in 1992. Despite this, it still contains a modest collection of manuscripts and documents in Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, Persian, and Bosnian, all of which have been digitized, and two collections of reference literature.

History

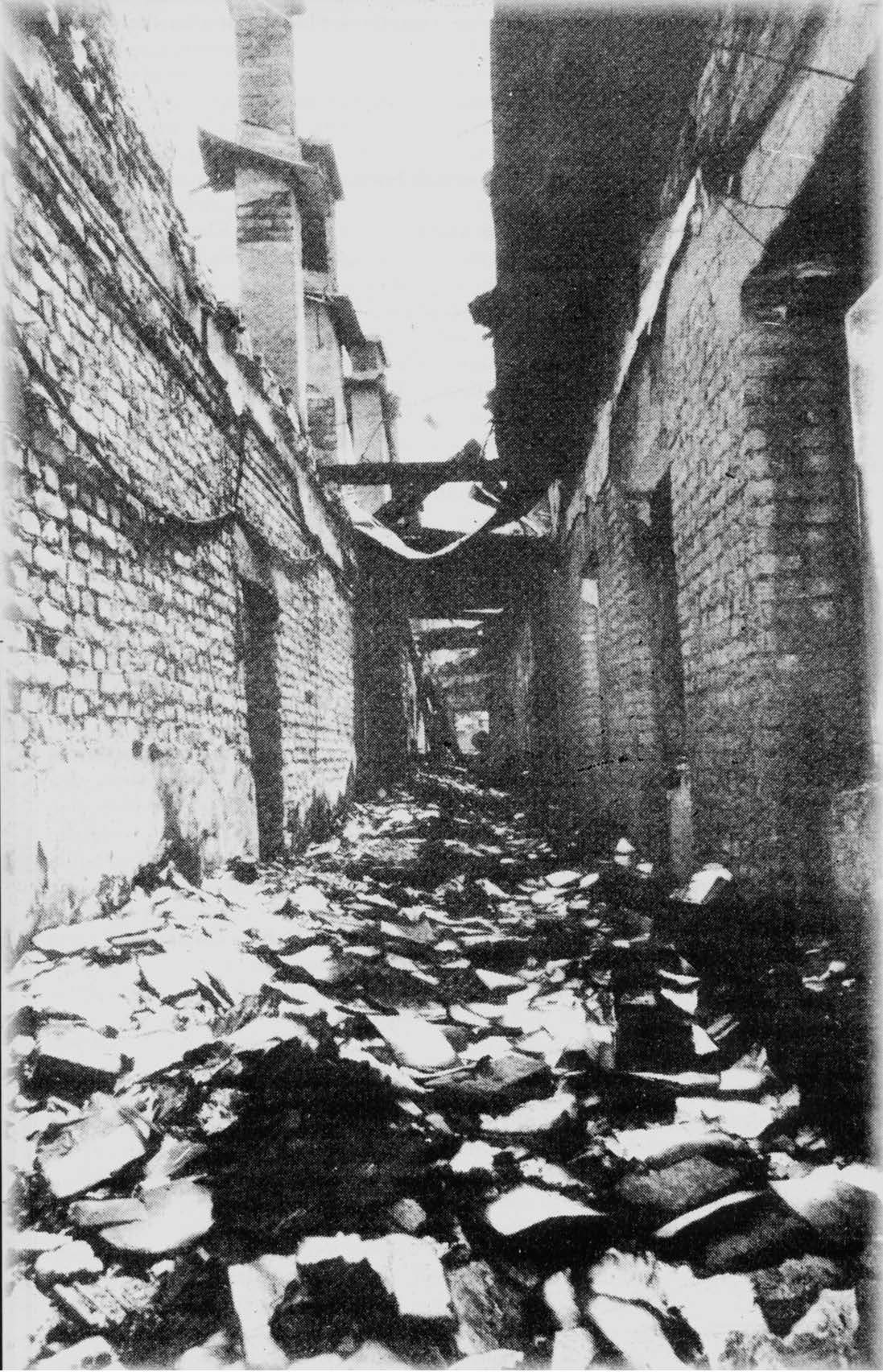

The Institute for Oriental Studies in Sarajevo was established in 1950 by the government of the People’s Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (RBiH). Between 1992-1995 it was proclaimed an institution of special relevance to RBiH, and after the war it came under the jurisdiction of the Canton of Sarajevo. The history of the Institute can be roughly divided into two parts, before and after the year 1992, which marks the beginning of the aggression against Bosnia and Herzegovina. During the first period, the Institute housed the manuscript collection and archives (in Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, Persian and Bosnian) of the National Museum. Apart from the collection and preservation of these materials, the Institute undertook research on the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Balkans in the Ottoman period, as well as the study of the languages, literatures and art of the Middle East. The Institute at its peak contained 5,263 manuscript codices covering fields from astrology and theology to epistolography and poetry, and the oldest manuscript in the collection was from the eleventh century. However, in May 1992, the Institute was hit by incendiary shells coming from the Serbian positions and the vast majority of the manuscript collection and archives was burnt and irrevocably lost.

Collections

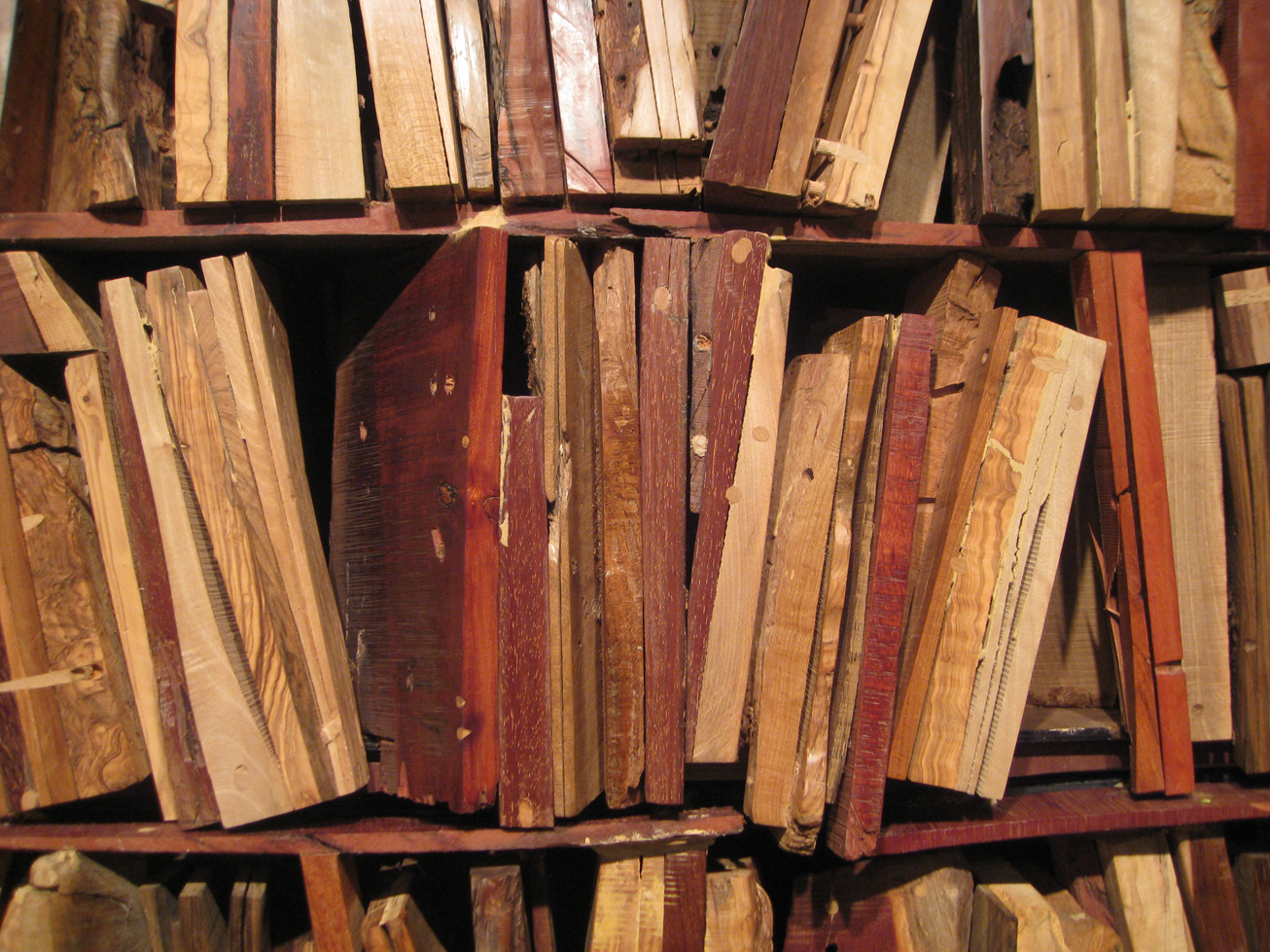

Manuscript Collection

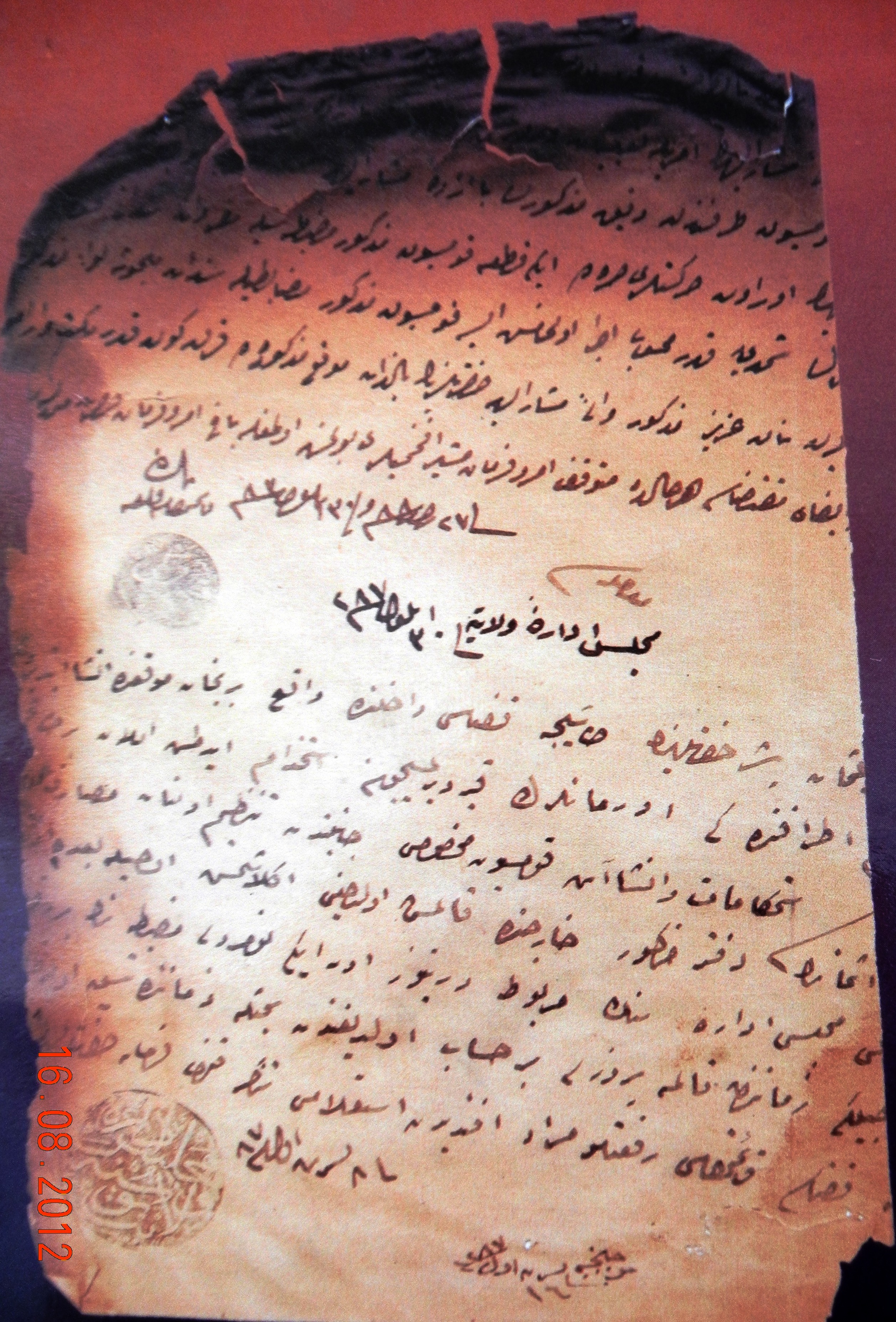

Today the Institute’s manuscript collection contains 53 preserved codices from the former collection of the Institute, 34 newly bought codices, and 21 codices received as gifts from individuals or institutions. The oldest codex in the collection contains two works and dates back to the fifteenth century. In spite of the relatively small number of manuscripts, Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, Persian and Bosnian works are represented in collection. The collection comprises manuscript copies of the Qur’an (either whole Qur’an or certain suras), commentaries on the Qur’an and related theological fields, prayers (ad’iya), works in Sufism, philosophy and logic, politics, medicine and pharmacopia, history, astronomy, astrology, grammar, adab, diplomas (ijazat), qanunnames, fatwas, epistolography, and a number of majmuas. Apart from the manuscript collection, the Institute for Oriental Studies in Sarajevo preserved nine sijills from the pre-war collection. The sijills are from various Bosnian cities (Mostar, Travnik, Jajce, Ljubinje, Prijedor, Visoko) and date mostly from nineteenth century though a few are from the seventeenth century.

The manuscripts in the new collection are of interest not only for their calligraphic value, but also for the fact that a certain number of them are autograph works of Bosnian authors in Arabic, Turkish and Persian. Researchers of Bosnian history and culture will also note the significant number of manuscripts by local copyists.

Printed Volumes and Special Collections

Since its establishment in 1950, the Institute’s researchers have published the results of their work in Monumenta Turcica (which contains translations and facsimiles of historical sources), Special editions (a series of monographs), and the journal Prilozi za orijentalnu filologiju (Contributions to Oriental Philology). The published studies largely focus on the history and literature of Ottoman Bosnia and the Balkans. These publications, however, are mostly in Bosnian, which makes them less accessible to a wider academic public. Some of this journal’s articles are now of crucial value since they are our sole source of information about manuscripts and documents which were lost in 1992.

Apart from these publications, the Institute’s library contains more than 10,000 volumes and 180 serial journals (around 50 are in local language(s) and 130 in foreign languages). The largest part of the library collection contains books on Ottoman history (especially the Ottoman Balkans), general history, literatures and cultures of Bosnia and the Middle East, Islamic art and architecture, etc. The secondary literature is predominantly in Turkish, English and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, but works in Arabic, Persian, French and German can also be found. A second, separate library collection is the Hadžibegić Library, named after Hamid Hadžibegić, one of the Institute’s researchers who donated his private library to the center in 2001. This library comprises more than 1000 volumes, as well as a certain number of journals. The works are primarily in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian but there are also some in Turkish, especially when it comes to books dealing with Ottoman history, architecture and literature. There is also a significant number of dictionaries, grammars and language instruction books.

Research experience

The Institute has two comfortable reading rooms, one larger and one smaller. A paper catalog is available though there is no computer catalog. The material listed in the paper catalog is digitized, and can be seen upon request (on CD). Researchers can see the original material, but only in the presence of the librarian or archivist. The manuscript material and the sijills can be seen the same day upon arrival. The same applies for the reference literature from both of the two library collections. Manuscripts, however, have been digitized and may be viewed as high-quality photographs on the computer.

The librarian and the archivist (who are also researchers at the Institute) are very helpful. They speak English and Turkish. The rest of the staff (eighteen researchers in total, consisting of Arabists, Ottomanists, and Persianists) can be consulted if there is any specific question related to the material.

Access

The Institute is officially open to researchers and students Monday to Friday from 9:00 to 11:00, but they can usually stay until 15:00. There are no long-term closures and researchers can come in every part of the year, but they should keep in mind national as well as Islamic religious holidays when the Institute is closed for a day or two. It is highly recommended for the researchers to send an email announcing their visit a couple of days prior and to remember to bring their passport (in the case of foreign researchers and students) or ID (in the case of Bosnian citizens). They are supposed to email the librarian of the Institute, Ms Mubera Bavčić. The whole process is very straightforward. The library membership fee is 10 KM (approximately €5).

The Institute is not wheelchair accessible.

Reproductions

Digitized manuscripts and the archive material is available for free in CD format, but the researchers should keep in mind that the amount of material which will be given is limited. The reference material can also be copied for 0.20 KM per page (€0.10).

Transportation and Food

The Institute is located on the campus of the University of Sarajevo. It can be reached by bus, tram (all the tram numbers apart from number 1), or a twenty-minute walk from the center. The Institute is also a five-minute walk from the Faculty of Philosophy.

Across the street from the campus, there is a shopping mall with several eating options, of which the small restaurants in the mall and the adjacent building are the most suitable in price and quality.

Contact information

The Institute for Oriental Studies in Sarajevo has a website with some useful information; however, it is only available in Bosnian at the moment.

Website: www.ois.unsa.ba

Address: Orijentalni institut u Sarajevu

Zmaja od Bosne 8b

Sarajevo 71 000

Phone: 00 387 33 225 353

Email address: ois@bih.net.ba

Resources and Links

The catalog for the collection is not accessible on the internet. There are three paper catalogs published by the Institute, however, only the latest one deals with the collection in its present state:

Institute for Oriental Studies in Sarajevo. Catalogue of Arabic, Turkish, Persian and Bosnian Manuscripts (prepared by Lejla Gazić). London-Sarajevo: Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation and Institute for Oriental Studies, 2009.

These are the paper catalogs of the material no longer existing in the Institute:

Orijentalni institut u Sarajevu. Katalog perzijskih rukopisa Orijentalnog instituta u Sarajevu (obradio Salih Trako). Sarajevo: Orijentalni institut u Sarajevu (Posebna izdanja), 1986.

Orijentalni institut u Sarajevu. Katalog rukopisa Orijentalnog instituta – Lijepa književnost (obradili Salih Trako i Lejla Gazić). Sarajevo: Orijentalni institut u Sarajevu (Posebna izdanja), 1997.

___________________________________________________________

Dzenita Karic is a researcher at the Institute for Oriental Studies in Sarajevo, currently working on a project of Hajj travelogues in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Cite this: Dzenita Karic, “The Institute for Oriental Studies in Sarajevo,” HAZINE, 10 Feb 2014, https://hazine.info/2014/02/10/oriental_institute_sarajevo/