Although Latin has become the dominant script in West Africa, one Nigerian calligrapher, Ustadh Yushaa Abdullah, has made major efforts to bring back the culture of the Arabic script to the region. Yushaa, who completed his studies in Turkey, is West Africa’s first certified calligrapher (he holds an ijazah). Here, we talk to him about his work, what led to his interest in Arabic calligraphy and the school he founded to teach various Arabic calligraphy scripts to students in Nigeria and the Republic of Niger. Yushaa also plans to develop a teaching technique alongside Nigerian scholars to more widely disseminate the rules for writing the traditional Arabic Hausawi script, which was developed in West Africa and is still taught to children in Nigeria today as part of their Islamic studies training.

What drove you towards learning Arabic calligraphy? Did anyone influence you in this direction?

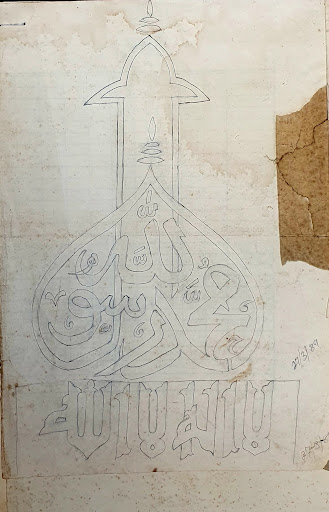

During my secondary school days, I subscribed to the Iranian monthly news magazine Echo of Islam, which contained beautiful calligraphy artworks. This led me to become so passionate about calligraphy and my passion pushed me to try my hand in imitating those calligraphy artworks using ordinary pencils. The replicated artworks attracted the attention of people in my community. They started placing orders, and their patronage became a source of income for me, allowing me to develop a strong interest in the field. I pledged to further my academic career in Arabic calligraphy. Unfortunately, though, I could not find any institutes or learning centers that offered training in Arabic calligraphy in the Black African region. Upon graduating from secondary school in 1987, and being the best chemistry student and winner of a chemistry competition in Bauchi State in Nigeria, I secured automatic admission to study chemical engineering at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, but declined the admission in order to not allow anything to divert my attention from calligraphy. I continued to work as a full-time artist, offering calligraphy artworks to mosques, schools, homes and other Muslim buildings. Over the years, I became well known in the mosque decoration business in Nigeria and neighboring countries.

In the meantime, I continued searching for admission overseas through correspondence to further my education in Arabic calligraphy. After 20 years of struggle, I became successful only in December 2007 when I got an invitation from the Research Center for Islamic History, Art and Culture (IRCICA) to study with Grand Master Hasan Çelebi in Istanbul, Turkey, giving me the opportunity to become his first Black African student. By virtue of being his first Black student, I took it as a challenge to return home and spread what I would learn from him and other supportive teachers.

You have an ijazah in Arabic calligraphy and you have granted students ijazat yourself. How and with whom did you learn Arabic calligraphy? How have you applied your knowledge of Arabic calligraphy in Nigeria outside of teaching?

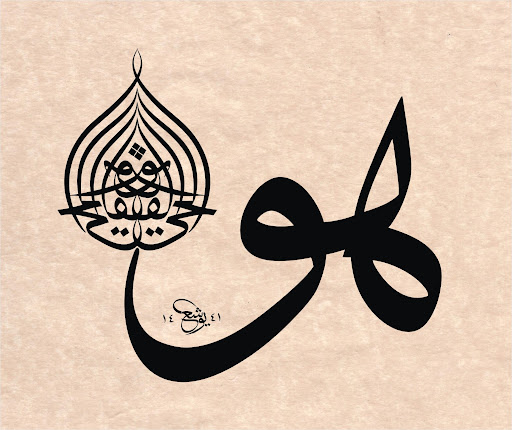

I studied both the Thuluth and Naskh scripts with Grand Master Hasan Çelebi, Hattat Ferhat Kurlu, and Hattat Mumtaz Durdu from 2008 to 2013, so my ijazah carries three endorsements from three different masters. I also took some lessons with Hattat Davut Bektaş and Hattat Efdaluddin Kılıç. I granted ijazat in both the Thuluth and Naskh scripts to three of my students in 2018, five years after my own graduation.

Before acquiring formal knowledge in Istanbul, I had been practicing calligraphy as an amateur artist, and as such, I had a lot of experience working with mosque decoration and producing calligraphy frames for homes and offices. So, after obtaining my ijazah, I revisited my previous artworks and restructured them with authentic letters and compositions in accordance with the rules governing the art of calligraphy, making my present projects more standard than the early ones.

You run an IRCICA regional calligraphy center in Kaduna that is dedicated to teaching Arabic calligraphy and disseminating your expertise in Nigeria. Can you tell us more about it and its pedagogical structure? What sorts of students do you get? How do you advertise the center?

After my graduation from IRCICA, and upon my return to my country, I organized a two-day workshop for the general public in order to create awareness around the art of Arabic calligraphy. Many of the participants showed interest in learning Arabic calligraphy and becoming calligraphers, which led to my decision of opening a training center that would allow any interested participant of the workshop to learn Arabic calligraphy. I was able to achieve all of this through my own personal effort.

After five consecutive years, three students were able to complete the curriculum and, therefore, obtained their ijazat in 2018. I took their ijazat to Istanbul for approval from the Grand Master Hasan Çelebi and they were all approved. The three ijazat were also presented to the then Director General of IRCICA, Professor Halit Eren, who was highly impressed by the students’ performance, leading to his decision of allowing the training center to be managed by IRCICA. He later came up with the idea of expanding the center’s training activities to allow it to encompass the West African region. I have been given a contract appointment as IRCICA personnel to carry out the project. In the same year, an official launching of the center took place in Abuja, the Nigerian capital, and it should begin activities shortly. Upon his assumption of office, the new IRCICA Director General, Professor Dr. Mahmud Erol Kılıç, emphasized the importance of the project: students from West African countries will be admitted to the training center in Nigeria under the sponsorship of IRCICA. We now have about 11 licensed calligraphers who can teach, and it is my hope that the project will be executed smoothly. The students are mostly young talented artists who have already developed their passion for the art and are searching for a way to develop their skills. I also have students who are graduates of different disciplines, such as Medicine, Law, and I even have one student who is a Professor of Archaeology.

I advertise the training center through brochures containing pictures and text on the center’s training activities as well as the achievements attained by me and the center’s most senior students. The production of printed calligraphy frames carrying our contact information also attracts media houses that come for interviews, allowing the training center to gain more popularity.

You’ve worked on decorating mosques in Nigeria. Can you tell us more about this?

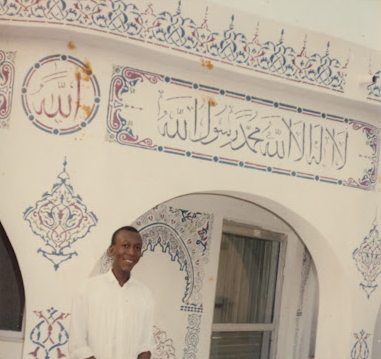

The mosque decoration business started in 1990 when I was an amateur artist. After conceiving of the idea of decorating a mosque, I contacted the management of one mosque in my neighborhood and asked them to permit me to decorate the mosque free of charge. However, as this was entirely new to the culture here, the committee of the mosque debated the issue thoroughly before they finally granted me permission. It gave me the opportunity to execute the idea I had conceived of and it also became an example I could give to other clients.

After the completion of my first mosque decoration project, I took some pictures of my work and started going around the city with the sample, searching for more projects but only in 1992 did I succeed in finding another project. It was this second project that got noticed and from there on, I started receiving commissions from across the country and the neighboring Niger Republic. The mosque decoration tradition has become very popular amongst Muslim communities in both Nigeria and the Niger Republic.

What Arabic scripts do you work with the most? Which scripts are your favourites?

Thuluth Jali is my favorite script because of its beauty and flexibility. I use it in almost all of my mosque decoration projects and creative art compositions. I love the Naskh script too but I used it infrequently in my previous work. I am currently receiving training in the Diwani, Riq’ah and Nastaliq scripts from my Turkish masters so that I can give our students a range of options for scripts to learn.

Although the Arabic script is not common today in Nigeria, there are Arabic scripts that were used prior to the adoption of the Latin script, like the Hausawi script. What can you tell us about their development, appearance and use?

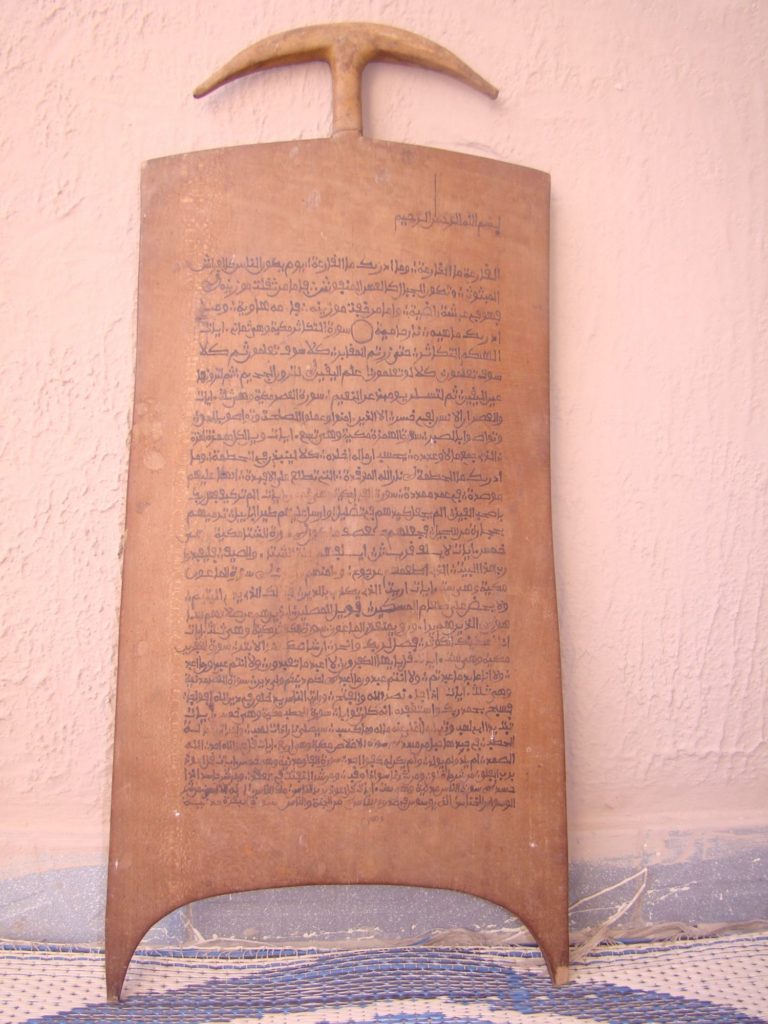

Islam came to Northern Nigeria from North Africa through trade and the script used by North Africans was Maghribi, making it the first script known to our scholars. The same Maghribi script was later modified to suit our local language for easy written communication. As such, the Hausawi script is a modified form of the Maghribi script. For many centuries, the Hausawi script was popular in the whole region of West Africa and it was used to write numerous copies of the Holy Quran and other Islamic Books. In the late 1950s, when Muslim students in the region started having opportunities to study abroad in Arab countries, they started bringing back books that contained Arabic scripts other than the Hausawi script. However, at the time, these scripts were considered foreign and, therefore, they were not given much attention. My own father was an Islamic scholar and expert in the Maghribi script, and while receiving my Islamic education at home at an early age, I was taught to write and read in the Hausawi script. My father wrote some verses of the holy Quran on a plaque in the late 60s and kept it as his masterpiece because of his passion for beautiful writing. Alhamdulillah, that piece of artwork was passed on to me much later by family members after they noticed the career path I had chosen for myself.

Besides calligraphy, you have also done logo design work. How has this background in graphic design influenced how you produce Arabic calligraphy artwork? How has the digital medium influenced your work?

As young as 8 or 9, I was curious about all sorts of artworks in my surroundings, including on walls, billboards and banners. I wondered how the graphics were created and I tried copying many of them myself. Since then, I started creating drawings that attracted the attention of my immediate community and I taught myself how to draw the Latin letters. When I decided to become a graphic designer, I designed a logo for my own business in March 1989, and this was my very first logo design. The name of the business –which combines the names of my parents Abdullahi and Khadijah– is ABDUKHA GLOBAL ARTS. The logo impressed many people who commissioned me to design for them as well. I designed my logo with the big dream of seeing my artwork circulating across the world, and by Allah’s permission, today I am living my dream, alhamdulillah.

Logo design is a sort of art form that requires a high sense of creativity because it involves bringing something that has never existed into existence for use as an identity for either individuals or organizations. Although I am a self-taught logo designer, my previous logos –both those completed manually and those digitized– have been examined and commended by a graphic design professor in the Graphic Design unit of Ahmadu Bello University, alhamdulillah.

Having had long experience with both Arabic calligraphy and Western art through self-taught practice, I believe that many forms of art can be learned and practiced individually at a high level by a gifted artist, but that is not possible with Arabic calligraphy. I started practicing Arabic calligraphy as a profession in 1989 and I decorated many mosques across Nigeria and produced countless posters until 2007. However, upon my arrival in Istanbul, I discovered that no letter I had ever written was in accordance with its rule. The art of Arabic calligraphy is hidden in the hands of its masters.

“I believe that many forms of art can be learned and practiced individually at a high level by a gifted artist, but that is not possible with Arabic calligraphy.”

The creativity involved in logo design has influenced my calligraphy compositions a great deal because, like logo design, calligraphy brings together the idea of coming up with a never-seen-before concept and the importance of the ability to communicate visually. For example, there was a call for artwork submissions for an international art exhibition in 2012 by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Istanbul where the theme of the exhibition was the Art of Migration. In order for a given artwork to qualify for the exhibition, it had to be visually related to the concept of migration and an essay had to describe it. One of my submissions, titled Ark of Beauty, depicts an imaginary ship –a calligram composed using an Arabic calligraphic style– which I metaphorically used to migrate to Istanbul to study calligraphy, the art of beauty. The other work I submitted, titled Migrating Goose, is also a calligram of a goose, which is known to exhibit behaviors associated with migration from one location to another. Amazingly, I emerged as the only calligrapher in the midst of other visual and conventional artists in the event. The two artworks were sold during the exhibition period and I also received three orders after the exhibition, two of which came from non-Muslim Swedish diplomats.

It was an exciting and unique event in which the visual effects of Arabic calligraphy and other conversational paintings were displayed together hand in hand to convey a common message. It was during this exhibition that I was noticed by the organizers of the Islamic Art Festival of Malaysia, and I was eventually invited by them in 2013 to participate in their festival with two artworks. I am also displaying three artworks in an exhibition taking place next year (2022) from March 7 – 11 in Paris, in sha Allah.

I consider digital tools as modern means that allow us to serve the needs of our digital age. If you trace back the history of tools used by old calligraphy masters, the early ones had no access to the tools we have today –like ordinary calligraphy paper, tracing paper, and pencils– to sketch out compositions, so they used the available tools of their time. If the aesthetic nature of the original letters drawn by these old masters is to be maintained in the process of mass production printing, the calligraphers of today should master the use of computer programs for graphic design, so that they can manipulate the letters they draw professionally without requiring other hands. I learned how to use the CorelDRAW program by enrolling in a computer training center in the 2000s, and by later employing the service of a CorelDRAW specialist who came to my house to give me lessons. I mastered the program after a series of assignments that involved producing graphic designs. Having accumulated enough experience using the program, I then started using it to digitize my calligraphy compositions. The program makes it easier to measure, position and mirror my letters. The Karalama method was used and is still in use by some calligraphers where the calligrapher writes numerous letters and selects the best ones for insertion into their composition. This method is so tedious, but using a computer can be a substitute and easier tool for carrying out the Karalama exercise.

“… the calligraphers of today should master the use of computer programs for graphic design, so that they can manipulate the letters they draw professionally without requiring other hands.”

For these reasons, I have made it mandatory for my students to learn how to use the CorelDRAW program by giving them lessons on specific days. However, I always emphasize the need and significance of learning and mastering the traditional methods for their aesthetic values and in order to preserve the valuable methods that were employed by old masters.

Your artwork has been sold through platforms like Cambridge Islamic Art, which has also sold work done by your students. Can you tell us more about where you’ve sold your artwork and how and by whom you are approached? What is your sense of the art market and its customers?

Yes, two of my works have been sold through the Cambridge Islamic Art online exhibition. One is titled On Dots Between Two Dots, which was sold at the rate of £2000, and the other one, titled White Tulip, was sold at the rate of £1500. Two years later, two of my students, Idris Umar and Abdulnasir Sirajo, participated in the same exhibition with two artworks each and, alhamdulillah, all four of their artworks were sold.

As I have mentioned, two of my works, titled Ark of Beauty and Migrating Goose, were sold in an international exhibition organized by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Istanbul in 2012. In 2013, another work of mine, Beautiful Tree, was sold in an international exhibition in Lahore, Pakistan, and, in 2016, On Dots Between Two Dots was sold in Kuwait City, Kuwait. The works Ihsan and Huwal Hayyul Qayyum were all sold in the Dubai International Calligraphy Exhibition in 2017, and Huwal Ganiy was sold in Amman, Jordan in 2018.

The art market of the present day is determined by the level of art appreciation in a particular country and the number of elites in its society. The economic situation of the people in a given society is a determining factor of the extent to which people can afford to buy artwork. Artists should take advantage of modern printing technology to reproduce their original artwork so that it can be affordable to a larger number of art enthusiasts.

You make use of your immediate natural environment to produce bamboo qalams for use in Arabic calligraphy. How did you gain this knowledge and expertise? What other equipment do you offer students in Nigeria? How do you come by them? What materials do you import and do you export any materials? Can we buy any tools you make online?

Upon my return from Istanbul, I brought with me a quantity of traditional tools but I faced the challenge of finding similar tools in Nigeria, especially since I had an increased number of new students. I knew that the plants we use to make calligraphy qalams are usually found in swampy areas or by riversides, so I decided to visit the Kaduna River in search of the plants and I was lucky to have discovered a variety of such plants by the riverside. Now, the qalams made from these plants are used by both myself and my students, as well as some of my colleagues from Istanbul who order these qalams from us. Any interested buyer from any part of the world can also buy from us.

What work are you currently undertaking? Do you have any projects planned for the future?

I am currently working on three pieces of art, using oil on canvas, in preparation for a painting exhibition in Paris that will be taking place from March 7 – 11 next year. The artworks portrayed include The Green Dome of Medinah, the beautiful names of Allah in a tree, and Ark of Beauty. In the future, I plan to prepare more ijazah-holding calligraphers with the aim of distributing them to all the regions of Black Africa so that they can transmit their acquired knowledge to students in these regions. I am already in the process of setting up a complete production factory for the production of unoriginal artworks by myself and my students for internal consumption and export as well.

Who are some artists who are new on the scene and inspire and excite you? What are your hopes for the next generation of calligraphers, locally and globally?

I am generally impressed by young calligraphers and students who have a sense of creativity and determination towards achieving their goals. It is my hope and fervent prayer that the calligraphers of future generations can better uplift the status of the calligraphy industry here in Nigeria, West Africa and at the global level. It is my strong belief that my students will be my legacy after I am gone, so my prayers for them is that they perform better than I.

*Disclaimer: This interview was commissioned in February of this year. The responses to the above questions contain similarities to a recently published interview on Scripts ‘n’ Scribes.

Yushaa Abdullah was born in the town of Bauchi in northern Nigeria in 1968. He is West Africa’s first certified Arabic calligrapher. He began studying Arabic calligraphy individually before receiving an invitation to study under the mentorship of various renowned calligraphers in Istanbul, Turkey. Today, he runs an IRCICA regional calligraphy school, which he founded in Kaduna, Nigeria and where he teaches Arabic calligraphy. He is also a graphic designer who has experience with logo design and he has decorated several mosques in Nigeria and Niger using Arabic calligraphy.

Masha Allah congrats Hattat yushau Abdullah is one of my favourite master that I can’t forget in my life, he told me Arabic Calligraphy,and insha Allah we will spread this Calligraphy in West Africa

Maasha ALLAH!

Alhamdulillah wa jazakaAllah khayr Ustadh Yushaa Abdullah for this informative article however at the same time I would categorize this as Eastern Arabic calligraphy in West Africa whereas I would consider “Mahiru” (the “skilled one”) master calligrapher and scholar Auwalu Sharif Bala Gabari (known variously as Shaykh Jaafar Bala, Gwani Mahiru Sharu Bala, Sharif Bala Gabari or Sharif Bala Zaytawa) Kano, Nigeria who’s style is greatly desired in Nigeria as truly representative of actual West African Arabic calligraphy. May Allah bless those who beautify the written words of the Qur’an

Brother Akil, thanks for your comment . However you need to know how Arabic calligraphy scripts are being categorized by the old masters of the art, before mentioning something about Hausawi script and the people who practice the script. The script has been extracted and modified from Magrib script. Hausawi script has been in West Africa many centuries before all the calligraphers you mentioned were even born. And this article is talking about the emergence of “Suluth” and “naskh” scripts in West Africa. Suluth and Naskh scripts are categorized as the highest artistic scripts of all the Sixth major scripts of Arabic calligraphy. Master Hashim Bagadadi known as The Imam of Calligraphers mentioned in his book (Khattul Arabiy) that ” No calligrapher can be addressed as “Hattat” if he does not writes Suluth script. So brother Akil, Arabic calligraphy scripts are not categorized as “Eastern or Western”.

Do you have a channel in YouTube?

MashaAllah Alhamdulillah Tabarakallah, more grease to your elbow. N

This is truly truly inspirational!!! Allah ya qara daukaka sir!

Masha Allah, I was opportuned to be one of the most senior students of HATTAT yusha, you are doing great job sir, may Allah swt. Makes every plan of yours easy amin.