Written by Christopher Markiewicz

Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran (WWQI) is a digital archive of materials related to the social and cultural history of Iran during the Qajar period. The archive seeks to aid scholarship on women’s history and gender history by making freely available online a vast array of writings, photographs, financial and legal documents, artwork, and everyday objects contained in private and public collections around the world. In this way, the project seeks to assemble a digital archive of Iranian culture during the long nineteenth century (1796-1925) with a focus on women and issues of gender.

Background and History

The idea for a digital archive of Iranian material on women’s history originated in the early 2000s. In 2009, Afsaneh Najmabadi, along with four scholars of Iranian history (Nahid Mozaffari, Dominic Brookshaw, Naghmeh Sohrabi, and Manoutchehr Eskandari-Qajar) were awarded a grant by the National Endowment for the Humanities to assemble a digital archive of documents from a number of private collections and public institutions. The original idea for the project arose from an awareness of the state of Iranian archival resources and of the possibilities afforded by emerging digital technologies. Firstly, the project members recognized the need for assembling an archive for Iranian history in the absence of extensive institutional archival collections. In contrast to the large state archives for the Ottoman Empire, which are preserved by various state institutions in Turkey and the Middle East, no analogous institutional archives exist for Iranian history prior to the twentieth century. Despite this lack of formal institutional archiving, the project members knew of the existence of significant numbers of documents from the nineteenth century that have been preserved in the private collections of families throughout Iran. Secondly, the development of high quality digital technologies made possible the establishment of a virtual archive composed of disparate collections held in various locations. Rather than construct a physical archive on the basis of a state’s backing, the project has endeavored to collect (or “fabricate” in the words of Najmabadi) within a single website a digital archive of material from around the world.

The project has focused on women in nineteenth-century Iran for several reasons. First of all, the archive seeks to address a lacuna in Iranian social history with regard to women and gender issues. The absence of more scholarly work on women’s history for Iran is surprising considering the relatively rich material produced by women or related to women from the period which sheds light on the daily lives, social relationships, and cultural activities of Iranians during the Qajar era. Moreover, much of the material preserved in private family collections—including marriage contracts, diaries, and photographs—provides a detailed and unique view of women’s worlds. In this way, the nature of the archival material preserved in disparate private collections demands scholarly attention to aspects of women’s history.

Collection

Initially the project envisioned an archive of 3,000 images. By April 2013, the collection had grown to more than 33,000 images. The majority of the archive’s images are owned and held by forty-three private collections. In addition to these collections, WWQI has partnered with ten public institutions to make available a number of other documents and objects on the project’s website.

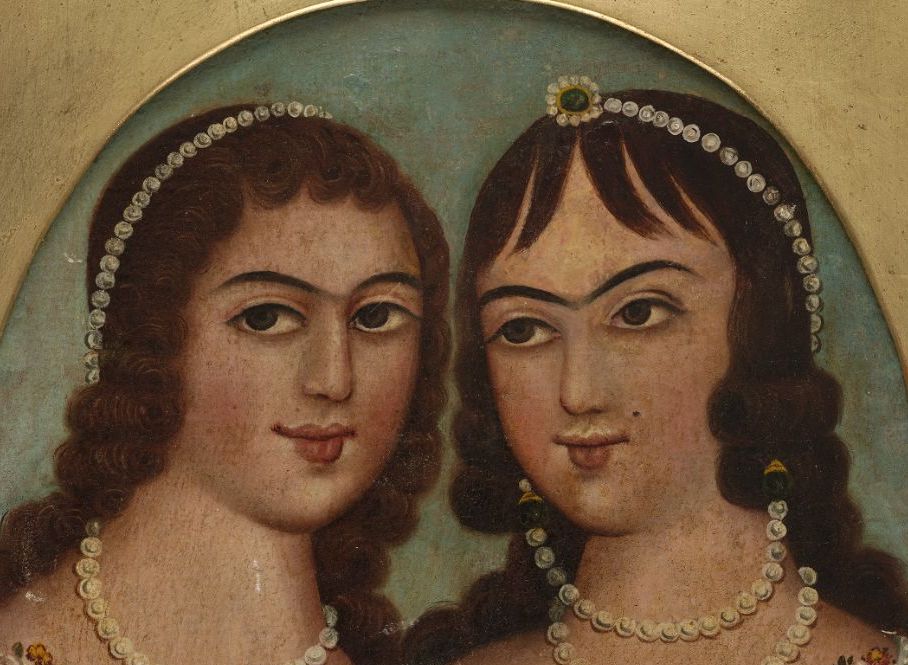

In general, the private collections consist of individual families’ records and therefore reflect the eclectic documents and material objects preserved by a single family over the course of several generations. In some instances, the private collections consist of the personal archives of a local notable, such as a mujtahid or kadkhuda, and consequently contain an array of financial and legal material that had been entrusted by a number of families to the local leader for safekeeping. The images found within the private collections usually range from documents of legal significance, such as marriage contracts and sales of property to documents of a more intimate world, such as photographs, diaries and letters, as well as antiquated objects of daily use. Assembling this digital collection from a disparate array of smaller collections enables scholars to develop a more thorough understanding of various social phenomena. For instance, WWQI has managed to gather and make available more than 300 marriage contracts from Muslim, Jewish, Armenian, and Zoroastrian communities. This sort of collecting allows for more systematic approaches to issues such as kinship and family. Similarly, the inclusion of large numbers of photographs invites researchers to examine relatively underused historical sources. Unfortunately, given the nature of these private collections, which are largely the holdings of relatively prominent families, the archive mostly reflects the interests and priorities of the urban upper class. WWQI is aware of this shortcoming and is working to alleviate the imbalance by actively soliciting archival contributions from families with significant rural ties.

The other major source for WWQI’s image archive is provided by a number of public institutions in Iran and abroad. These institutions range from important libraries, such as the Majlis Library in Tehran and Tehran University Library, to academic institutions, such as the Center for Iranian Jewish Oral History and the Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies. The documents provided by these institutions tend to include state-produced material, published documents, and art objects. In this respect, the collection contains a number of journals and educational pamphlets, as well as legal documents.

The project has at least two great virtues. Firstly, by including objects of material culture (photographs, art, and instruments), the archive invites historians to practice their craft in new ways. For instance, the inclusion of large numbers of photographs from different families living in the same period enables researchers to read images not only as solitary documents from which evidence is extracted but as a comprehensive storehouse of social information which evoke an image of the age. Similarly, objects may yield equally surprising insights. Professor Najmabadi recounted one such experience while interviewing a family in Yazd. Despite initially doubting the usefulness of the family’s possessions, one family member returned to the conversation with kitchen ladles in hand, upon which had been engraved generations of family birthdays.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the archive’s digital nature allows for the relative ease of its expansion. As contributors to the collection maintain all of their rights of ownership, the archive need not engage in complicated arrangements to transfer and preserve material. In this way, the growth of the archive is only limited by individuals and institutions’ willingness to share images of their collection for scholarly use.

Research Experience

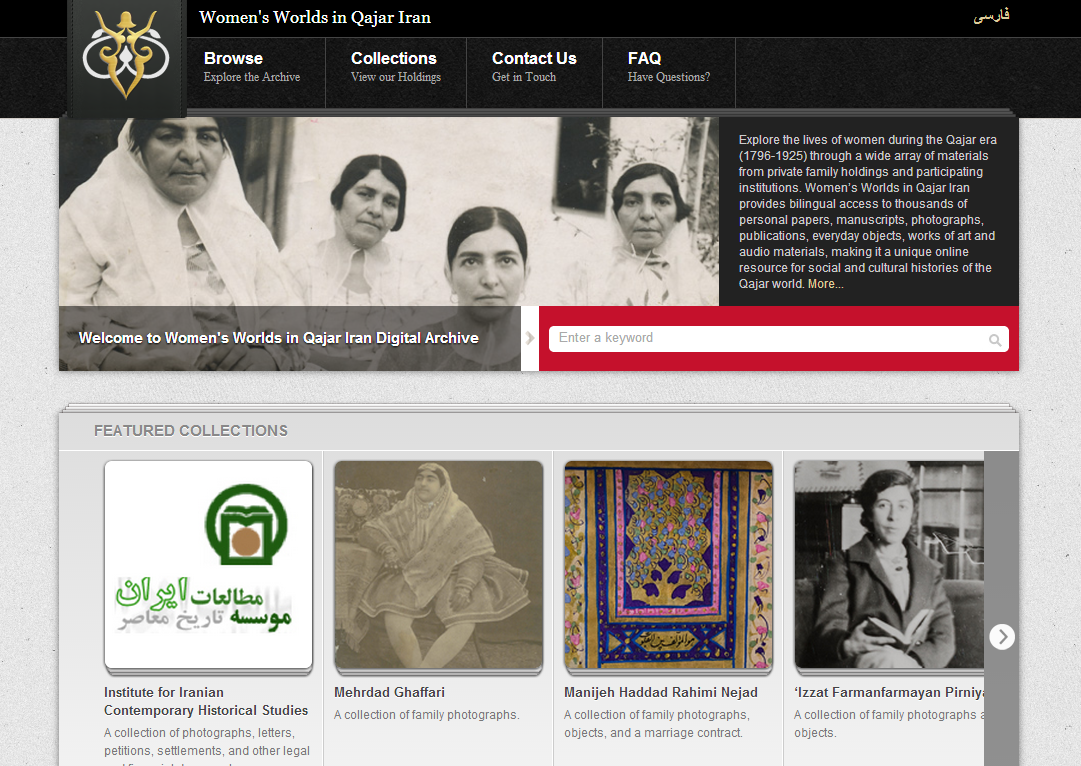

Researchers may search and access the archive’s collections through its website. The website is nicely designed with an easy to navigate interface and is fully functional in both English and Persian. Moreover, all of the documents within the collection are clearly and effectively labeled. While the site provides a platform to search and browse the archive’s collection, all of the images are digitized and hosted by Harvard University Libraries, so users are linked to Harvard’s library page once they have located a particular document that they would like to view.

There are three ways to locate material using WWQI’s site. The site has a simple search function located on the homepage which allows researchers to identify material according to names of people or places, the type of document (e.g. letter, marriage contract), or subject (e.g. politics and government, clothing and dress, kitchen ware). As it is hard to know how subjects are defined within the collection, it is probably best to browse the list of subjects provided from a link on the homepage.

Users may also locate material by browsing within particular collections. Here users will get a good idea of wide variety of disparate holdings that collectively constitute the project’s archive. This function will be of particular use to those interested in surveying the range of material preserved and donated by a single family.

Lastly, users may browse the archive’s holdings. This method is probably the most effective way to become familiar with the wide range of material available on the site. Users may narrow their browsing to a reign within the Qajar period or browse within a particular document genre (audio files, manuscripts, letters, etc.). In addition to these two subfields, users may also browse according to person, place, or subject, as well as view all of the archives materials which have been either translated or transliterated into Latin letters.

Acknowledgement:

I would like to thank Professor Najmabadi who provided me with a copy of a paper she presented on the project at Brown University in October 2013. Most of the details in this article originate from this paper.

20 January 2014

Christopher Markiewicz is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago where he studies fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Islamic history.

Cite this: Christopher Markiewicz, “Women’s Worlds of Qajar Iran,” HAZINE, 20 January 2014, https://hazine.info/2014/01/20/qajar-women-archive/