Written by Aslıhan Gürbüzel

The rich Oriental collections of the Leiden University contain some 6,000 Middle Eastern manuscripts, about 120,000 rare books printed before 1950, and photographs of interest to the scholars of the region. The collection is located at the Special Collections section of the main library of the university at Leiden, the Netherlands.

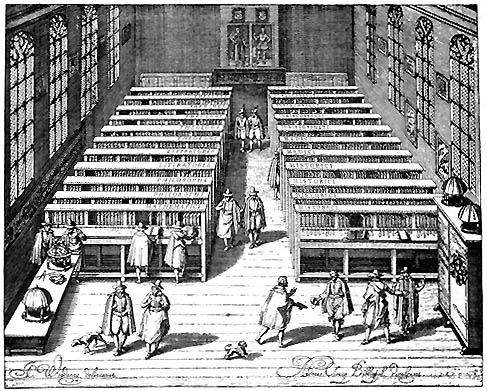

History

The study of Arabic at Leiden goes back to the late sixteenth century, when the university was established. The major figure of the earliest generation is Joseph Scaliger (1540-1609), the versatile and esteemed scholar who, through his fondness of collecting rare books, left a valuable collection behind that formed the nucleus of the Oriental Collection. Academic study of Arabic was soon to follow. The first scholar of Arabic was Franciscus Raphelengius (d. 1597), followed by two prominent scholars of the language: Thomas Erpenius (d. 1667), who wrote a grammar of Arabic and Jacobus Golius (d. 1667), who wrote an Arabic-Latin dictionary. The grammar book and dictionary of Erpenius and Golius remained widely read all over Europe up until the nineteenth century. The main driving force behind the pursuit of Semitic and Middle Eastern studies from this early period on was the study of the Bible and exegesis.

In addition to Arabic, Persian and Turkish were soon to become preferred languages of study due to Dutch political and economic interests in the Ottoman Empire, hence broadening the scope of the pursuit of knowledge of the Orient. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Arabic and Islamic studies were to be transformed by merging with the study of Indonesian languages and culture, a rapidly burgeoning field due to the colonial engagements of the Netherlands in the area.

Collection

Leiden’s large Oriental collection is divided into five sub-sections. The Hebraica, Judaica and Semitics collection consists of manuscripts and rare prints mainly in Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, but also the languages of Ethiopia, Old South Arabic, Coptic and Armenian. The South and Central Asian Collections comprise material in Sanskrit, Tibetan and Lepcha. This collection is remarkably rich in maps and visual material. The South and Southeast Asian Collections with its rich textual and visual Malay-Indonesian collection forms an especially strong component of the entire Oriental collection. Although the acquisition of manuscripts for this collection goes back to the sixteenth century, the real explosion took place in the second half of the nineteenth century, thanks to the needs of the colonial rule in the Netherland East Indies. The Japanese and Chinese collections, similarly, owes its strongest part, the Tokugawa era manuscripts and blockprints, to Dutch explorations on the Pacific ocean: the Dutch were the only European community permitted to reside on Japanese territory, though restrained to one island, the island of Deshima on Nagasaki Bay.

The Middle Eastern Collection houses the largest acquisition of the entire Oriental collections. This is the collection of 1,000 manuscripts inherited from Levinus Warner (d.1665), after whom the collection is sometimes referred to as Legatum Warnerianum, “Warner’s Bequest”. Levinus Warner started out as a student of oriental languages at Leiden. He then moved to Istanbul and lived there from 1645 until the end of his life, first as secretary and translator to a trading Dutch resident, Nicolaas Ghisbrechti, and as a diplomat afterwards. From the beginning all through his years of consular work, he never lost his bookish interests and formed a large personal collection including works on poetry, history, theology, medicine, and folk literature. His collection brings together material in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, oftentimes annotated in Latin. A remarkable acquisition of his is the private library of Haji Khalifa (Katib Çelebi), obtained through a local friend at an auction after the Ottoman scholar’s death in 1657. The Leiden collection currently holds manuscripts from the collection of Warner as well as his extensive personal notes, which touch upon Turkish proverbs, the intricacies of Persian poetry, daily events in Istanbul and many other topics. These notes are mostly in Latin, though occasional snippets are to be found in Turkish or Arabic.

The acquisitions of the library continued throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, mostly through the library’s purchases of individual collections or the bequests of individual benefactors. One remarkable example is the bequest of the Dutch businessman and diplomat A.P.H. Hotz (1855-1930). The bibliophile’s collection was obtained in 1934 and includes many travel books and early photographs, as well as well-preserved early modern manuscripts. Mention should also be made of the large collection that was bought in the 1960s, which presumably belonged to Sultan Murad V (1840-1904) and his heirs.

Research Experience

The catalog of special collections is helpful for navigating the oriental collection, although it is far from complete. The online catalog should not be ignored, since it will yield results likely not covered in the print catalogs. For best results, researchers should use the online catalog in consultation with the following printed catalogs.

Jan Schmidt’s three volume Catalog of Turkish Manuscripts is a gem of thorough scholarship, containing detailed information on each manuscript included. For works in Arabic, Petrus Voorhoeve’s Handlist of Arabic Manuscripts in the Library of the University of Leiden and Other Collections in the Netherlands is still indispensable. For Persian works, the researcher should refer to J.J. Witkam’s catalog of Persian manuscripts which is available in the reading room. Professor Witkam’s online cataloging project lists in digital format the library’s holdings acquired not only from the Middle East, but also from the South Asia and Southeast Asia, without regional division.

As the library has only recently begun to digitize its collection, only a small percentage of manuscripts have been digitized. In most cases, the reader will work with the original manuscript or print. The manuscripts and rare printed books are to be studied within the Special Collections reading room, using the necessary props. The reading room personnel are helpful, friendly, and knowledgeable. They all speak fluent English.

The collection is impressively user friendly. The reader places their requests online. The manuscripts then become available for pick-up within half an hour before 16:00, and the next morning if the request is placed after 16:00. Although there are no limits to the number of requests made, the reader is allowed to examine no more than two manuscripts at a time. This latter limitation does not apply to printed works.

Access

The Special Collections is open weekdays, 9.00 to 17.30 during the term and 9.00 am to 17.00 during the summer recess. To work at the collections, the reader must acquire a Leiden University guest card. The card can be acquired at the reception desk of the library in person, and is issued immediately. To acquire the card, the reader’s passport is required together with a fee of 30 Euros. Special discounts apply to the fee if the reader is a Dutch citizen or affiliated with a university in the Netherlands.

An important opportunity to keep in mind is the fellowships offered through the Scaliger Institute. The institute grants many research fellowships, in connection with the Brill and The Elsevier publishing houses, to researchers who want to explore the library’s holdings. For information, please visit the institute’s website.

Reproductions

The reader is allowed to photograph any material for free. For the purpose of use in publications, formal copies should be ordered through the library’s website. Online requests in this manner also stand as a viable option for readers who cannot visit the collection in person. Bear in mind that if the work has not been digitized yet, this process may take up to four weeks. The cost of a digital copy is 1 Euro per page.

Transportation, food, and other facilities

The library is located on Witte Singel, the main area where humanities buildings are located. It is a fifteen minute walk from Leiden’s Central Station, the hub of Leiden’s transportation. In terms of accommodation, finding short-term sublets in Leiden is easy during the summer months yet might prove difficult during the term. The Hague, which is a fifteen minute train ride away, is the next best option.

The library has a café which provides tosti (toasted sandwich, the staple lunch), baked goods and drinks. Richer lunch options are available, such as at the cafeteria of the Lipsius building right across the canal. The prices are reasonable in both cafes.

Contact Information

University Library (Main library and Humanities)

Witte Singel 27

2311 BG Leiden

Special Collections Reading Room:

Tel: 071 – 5272857

email: specialcollections@library.leidenuniv.nl

Resources and Links

The website of the Special Collections department

Online Catalog, with links for ordering digital images

Aslıhan Gürbüzel is a doctoral candidate at Harvard University working on the cultural and intellectual history of the early modern Ottoman Empire, currently focusing on Sufism in seventeenth-century Istanbul.

Cite this, Aslıhan Gürbüzel, “Leiden Rare Books Library,” HAZİNE, https://hazine.info/2013/12/13/oriental-collections-at-leiden-university/, 13 December 2013.

When will researchers be able to view and work on them

Hi Arzina, the collection is already open, according to our information.