Fixing academic publishing might very well not be possible or desirable: Producing an equitable system that makes knowledge open to all and eases the editorial process for all those involved in producing an actual work of history or art is well beyond the desires of the university press or the academic corporation (Routledge, anyone?). At Hazine, we like featuring those who think outside of the box and even the institution. We also like featuring projects that are just beginning their journey, so that, if you’re looking for new ways of thinking about the world around us, or thinking of embarking on a project yourself, you have others to turn to.

Even if fixing academic publishing might not be possible, the people developing the practices and perspectives we need are the ones who lay the path towards more equitable systems of knowledge production. Lamma, we at Hazine hope, will be amongst them. Formally Lamma: The Journal of Libyan Studies (Punctum Books), its first issue was released in 2020 and was a bright spot in the ‘academic’ publishing landscape: It is open-access, it featured content in Amazigh, Arabic and English, and it focused on Libya. It also dismissed the assumption that only academics should be involved in ‘academic’ spaces: In Lamma, artists and writers think together. In this interview, Lamma’s editors tell us how they conceive of their project, from how they practice compassionate editing to how Libya has been marginalized in academia and how they will counter its marginalization and dream of a Libya beyond the nation-state.

How did Lamma come about? How was the idea for Lamma conceived?

When we were graduate students, we all regularly encountered people researching a modern Libyan topic, but who were isolated and not in dialogue with other scholars of Libya. There was a lack of community, and the few existing venues did not seem invested in curating and publishing work on modern Libya. They also had a disconnect with Libyan scholars. In our experience, it was also difficult to find research on Libyan topics and connect with mentors, and even more difficult for students in Libya to do so. Initial ideas of how to address these issues included compiling an edited volume on a contemporary topic, or forming an association of scholars and students. But without any kind of regular funding, the latter seemed hard to implement, and on its own would not have created a platform for accessible research, which was the main goal. Once we became aware of major open-access initiatives like punctum books, an independent collective devoted to non-conventional scholarly work who ultimately became our publisher, and others, it was easy to decide that an open-access publication—especially one that blended academic work with essays, commentaries, reviews, and art—was the way to go.

When we were graduate students, we all regularly encountered people researching a modern Libyan topic, but who were isolated and not in dialogue with other scholars of Libya. There was a lack of community, and the few existing venues did not seem invested in curating and publishing work on modern Libya. They also had a disconnect with Libyan scholars. In our experience, it was also difficult to find research on Libyan topics and connect with mentors, and even more difficult for students in Libya to do so. Initial ideas of how to address these issues included compiling an edited volume on a contemporary topic, or forming an association of scholars and students. But without any kind of regular funding, the latter seemed hard to implement, and on its own would not have created a platform for accessible research, which was the main goal. Once we became aware of major open-access initiatives like punctum books, an independent collective devoted to non-conventional scholarly work who ultimately became our publisher, and others, it was easy to decide that an open-access publication—especially one that blended academic work with essays, commentaries, reviews, and art—was the way to go.

Who are your team members and how does your team work collaboratively?

The work of Lamma is truly collective and many different voices and perspectives have shaped its development. The editorial collective is composed of Adam Benkato, Leila Tayeb, and Amina Zarrugh, all of whom are Libyan American scholars. The editorial collective is responsible for the day-to-day management of the journal, including seeking out contributions, distributing submissions for peer-review, corresponding with authors, and finalizing and editing each issue of the journal. An active and engaged editorial board also contributes to reviews and advises the editorial collective. At every level, our team works collaboratively across multiple geographies to make critical decisions about how to identify innovative studies related to Libya, how to integrate a wide range of work into a single issue, and how to divide labor in ways that are equitable and manageable. Some of the most exciting aspects of our work together has been brainstorming future special issues that we think would engage and intrigue readers and offer alternatives to hegemonic ways of thinking about Libya.

How is Lamma innovative in the peer-reviewed publishing space?

As a peer-reviewed journal, Lamma is committed to publishing innovative scholarship, broadly conceived, that advances the field of Libyan Studies. We are especially committed to supporting and advancing the scholarship of junior scholars and view the peer-review process as an opportunity for mentorship across generations of scholars. Rather than serving as “gatekeepers” to publishing, we actively seek out reviewers who are committed to constructive feedback and to offering insights about submissions that enrich not only contributions to the larger field but offer fulfilling experiences to contributing authors. In this process, we seek to advance a more humane model of the research process and of academia more generally. As part of our interest in broadening the scope of scholarship about Libya and offering our readers a range of perspectives, Lamma is an open-access journal that is available to anyone, regardless of socioeconomic status. We also intentionally seek submissions from scholars in the broader North African region and scholars from Libya, whether they live in the country or are part of the diaspora. Our submissions are accepted not only in English but also in any contemporary language of Libya, including Arabic, Tamazight, and Tebu, among others. Collectively, these commitments represent a critical turn in peer-review publishing towards accessibility and centering a range of voices that, owing to the hegemony of English in scholarship, have been underrepresented in academia.

What have been the triumphs and challenges of launching a new peer-reviewed journal?

There have been many exciting aspects of launching a new peer-reviewed journal. One of the greatest joys has been the process of learning about incredible work that is being done about Libya around the world. This breadth of work ranges widely from studies of linguistics and gendered language to the translations of short stories by Libyan authors whose work will be positioned to reach new audiences. Our collective work at Lamma has also led us to further appreciate the rich and vibrant art culture among Libyans and non-Libyans alike, many of whom are asking critical questions about how we narrate the multiple meanings of Libyan social life. The experience has also been a humbling one as we have faced the challenges that accompany working as a small but committed team that is also balancing demands of our own writing and teaching. Like any new journal, we are seeking to build an identity and become a space for people to learn about and contribute to knowledge about Libya. This process takes time. We warmly welcome the contributions and support of anyone who is also committed to this kind of work.

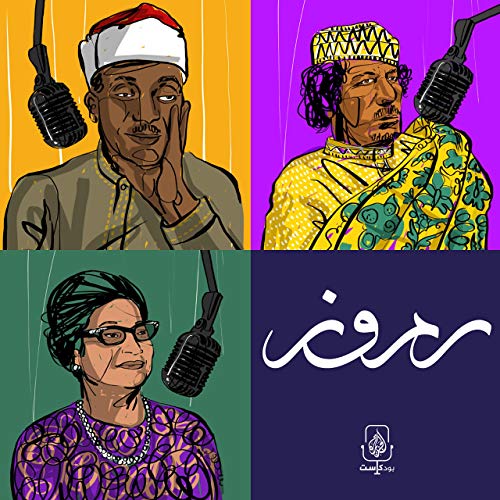

Tell us about Lamma’s visual identity, specifically the cover for the first issue.

As a journal dedicated to expanding the reach and relevance of Libyan Studies, our journal is shaped visually by the contributions of Libyan artists, photographers, and graphic designers. The cover of the first issue features the artwork of Tewa Barnosa, a Libyan artist now based in Europe, whose work broadly addresses the social construction of history, in particular how certain experiences and narratives are subject to erasure and denial. The piece featured on Lamma’s cover, called “Lost” (فُقد), is exceptionally fitting for the first issue of Lamma because it features a mid-century photograph of an iconic statue in Tripoli, referred to in short as the “Ghazala” by those living in the city, that has been a site of cultural contestation. The statue, designed by Italian artist Angiolo Vannetti in the 1930s, features a woman surrounded by water gently embracing a gazelle. A revered symbol to some, the piece went missing in 2014, shortly after the 2011 revolution. The statue’s disappearance symbolizes contested and competing perspectives on politics and colonization, gender and representation, and religious interpretation. As such, Barnosa’s piece complements the vision of Lamma as an intellectual space for readers to consider the ongoing impacts of history – that which is documented and ignored – for contemporary Libyan society.

If a writer was to submit to Lamma, what is the process like?

Given that we are in the early stages of Lamma’s development, we have had very intentional dialogues with potential authors about their research and how they might contribute to Lamma. We regularly invite scholars whose work we have seen presented at conferences or who have published in other venues, to contribute to our journal. This approach has not only been critical for us to grow the journal but also helps us curate a diverse set of scholarship, including from junior scholars in the academy. When a writer submits a manuscript to Lamma, we distribute the article for peer review, which often includes a member of our editorial board. We view the peer review process as an opportunity for mentorship and we dialogue directly with authors about how to incorporate constructive suggestions into their manuscript revisions. Please consult our website for further details on how to submit—we welcome your contributions!

How do you pay homage to Libya’s cultural diversity in Lamma?

We pay homage to Libya’s cultural diversity in a multitude of ways in Lamma. At present, we accept submissions in any language that is utilized in contemporary Libya. Given the institutionalized erasure of languages during the Italian colonial era as well as by the former regime, we intentionally seek submissions in languages beyond English and Arabic. Our journal’s mission statement first appears in the issue in the Indigenous languages of Tamazight and Tedaga, which were generously translated by Madghis Madi and Hasan Kadano, respectively. In addition, we highlight the work of Libyan artists, including those in the diaspora, on the cover of each issue. By inviting scholarship and artwork among the diaspora, our approach to Libyan Studies emphasizes the importance of thinking about diversity beyond the artificial borders that have come to define Libyan statehood.

What other Libyan cultural and academic projects are you excited about?

We are excited by a number of initiatives and projects, some curated by Libyan artists and researchers, and others by international networks of scholars.

Several grassroots, civil society initiatives in Libya that have a broad focus on the arts and culture are Bayt Ali Gana (Tripoli) and Tanarout (Benghazi). Unfortunately, these are under increasing pressure from oppressive state and non-state actors; for example, the Tanweer initiative (Tripoli) was recently forced to shut down and cease all physical and social media activities. Another initiative, initially based in Libya and now international, is the WaraQ Foundation which has curated a number of critical artistic interventions in Libya, in other countries, and online. The background of some of these initiatives is discussed in an essay by Hadia Gana, the founder of Bayt Ali Gana, in Lamma’s first issue. We are also excited by the Scene Culture and Heritage project based in Tripoli which aims to foster engaged participation and awareness of cultural heritage. Most recently, the architectural collective Tajarrod founded by Sarri Elfaitouri in Benghazi has done some critical and innovative work with public space; Elfaitouri describes his work in an essay upcoming in issue #2.

We would also like to mention ground-breaking literary projects like the fiction anthology شمس على نوافذ مغلقة (Sun on Closed Windows), edited by Khaled Mattawa and Leila Moghrabi in 2017. Publishing the short fiction of a wide range of new and established Libyan writers, it has also sparked discussion and controversy with various authorities who seek to control cultural productions. While it shines a much-needed light on the current promising state of Libyan literature, the public controversy has had difficult and discouraging consequences for some of the participating authors, such as Ahmed Bokhari and Leila Moghrabi herself, who no longer live in Libya.

Finally, we want to situate ourselves with respect to some other initiatives based in the Western academy which we hope will benefit research on Libya: the Center for Maghrib Studies at Arizona State University as well as the newly-launched Tamazgha Studies Journal (formerly CELAAN).

What are your goals for Lamma and for Libyan Studies overall? What sort of research would you like to see on Libya?

The name of the journal, Lamma (لمّة), means “a gathering” in Arabic and this term truly represents the spirit of the journal, which is designed to be an intellectual space for scholars, artists, activists, and practitioners to gather in conversation together. Rather than an academic journal that aspires to become the authority on all Libyan matters, the journal is instead a site where multiple ideas, perspectives, and conceptual approaches share space and are brought into conversation together. We envision Lamma as a place for multiple generations of scholars, artists, and activists to inform and shape one another’s approaches so that knowledge flows in many directions. The field of Libyan studies has long been disproportionately shaped by political scientists and non-academic policy experts whose research and writing has focused on top-down power structures and international relations. While undoubtedly critical issues to understand, the broader field of Libyan Studies must also speak to micro-level dynamics and ask questions about how individuals shape culture, politics, and institutions in Libya as much as the state has shaped individual lives.

We are particularly invested in a micro-level, socio-cultural shift in Libyan studies that foregrounds qualitative methods such as ethnography and in-depth interviews as well as longitudinal work that represents an investment in and commitment to developing knowledge about Libya that is deeply connected to communities and to Libyan people, who must be understood as subjects, rather than objects, in scholarship. We hope that the journal will become a place where this kind of approach to Libyan Studies flourishes.

Adam Benkato is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures at UC Berkeley, where he researches and teaches on late antique Iran and Central Asia and modern North Africa. He maintains a blog of old and new research on Libya, The Silphium Gatherer .

Leila Tayeb is a Humanities Research Fellow at NYU Abu Dhabi and an incoming Assistant Professor in Residence at Northwestern University in Qatar. Her research is in performance and politics in Africa and the Middle East. Her writing has appeared in the Arab Studies Journal, the Journal of North African Studies, Lateral, and others.

Amina Zarrugh is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Texas Christian University. Her research focuses on politics and forced disappearance in North Africa and race/ethnicity in the U.S. Her work has appeared in journals such as Ethnic and Racial Studies, Critical Sociology, Middle East Critique, Teaching Sociology, and Contexts, among others.